“He was a star in 1967, a time when the country’s entire political landscape was dominated by the Congress,” one Delhi BJP leader recalled. “The Jana Sangh was in charge of Delhi, and Malhotra was the chief executive of the Delhi Metropolitan Council. It was a pivotal time—Delhi’s statehood had been annulled, and it was declared a Union Territory. The chief of the Delhi Metropolitan was regarded as the de facto chief minister of Delhi.”

In his autobiography My Country My Life, Advani writes, “The decision to revoke the statehood of Delhi had not gone down well with its citizens. The Jana Sangh articulated their aspirations and became the first party to demand full statehood for the national capital. The party also led a mass agitation on this issue. As a compromise, the Central government consented to constitute the Delhi Municipal Council, which had the status of a deemed State Legislative Assembly.

“I had not contested the Council elections since I was entrusted with the responsibility of organising my party’s city unit for the three polls… The party then decided to field me as a candidate for the election of the Council’s Chairman. I won the election and became the Presiding Officer. Vijay Kumar Malhotra, my colleague in the Jana Sangh, became the Chief Executive in the Council.”

This was the pinnacle for Malhotra’s early political career. And then came the 1972 Delhi Metropolitan Council elections.

“Malhotra was contesting from Patel Nagar. Despite prime minister Indira Gandhi personally campaigning against him, Malhotra won, even with the backdrop of the 1971 war and her overwhelming popularity,” former Union minister Harshvardhan said.

“His work as chief executive was widely praised in Delhi. He was credited with transforming the city— ‘Delhi ko dulhan bana diya‘—due to his efforts in beautifying and improving the capital. I was in school at the time, and Malhotra was extremely popular then.”

A protege of Jana Sangh president Balraj Madhok, V. K. Malhotra played a key role, alongside Madhok, L.K. Advani, and Kedar Nath Sahni, in establishing the roots of the Jana Sangh in Delhi.

Malhotra’s work in Delhi, alongside the efforts of Madhok, Advani and Sahni, laid the foundation for the party’s growth and influence, positioning the capital as an early ‘Hindutva laboratory’, long before the political ideology gained prominence in other parts of India, especially under Modi’s leadership in Gujarat.

Also Read: Jana Sangh leader VK Malhotra brought Advani to Delhi, kept the party afloat after 1984 setback

Early life

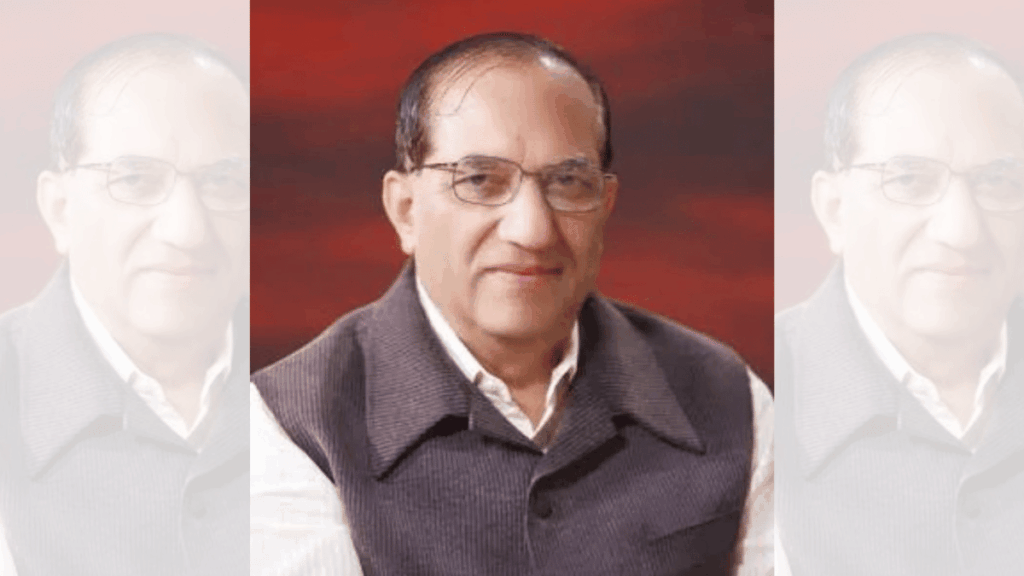

Vijay Kumar Malhotra was born on 3 December 1931 in Lahore in undivided India. He was the fourth of seven children of Kaviraj Khazan Chand.

One of the founding members of the ABVP, Malhotra was chosen the secretary of the Delhi Jana Sangh when it was founded in 1951. At the age of 27, he became a member of the Delhi Metropolitan Council in 1958 (and later its chief executive in 1967).

Malhotra served as the president of the Delhi Pradesh Jana Sangh (1972-75). When the BJP was formed in 1980, he became the founder-president of the party’s Delhi unit, shaping the party’s growth in the city along with Khurana and Sahni.

During the 1975 emergency, he was in jail with the late Arun Jaitley who was then the Delhi University Students Union president. Malhotra was also actively involved in the RSS-led Gau Raksha agitation in 1974. He survived a bullet shot he received during a protest.

The giant killer

The second biggest moment of Malhotra’s political career came in 1999 when he defeated Dr Manmohan Singh by a huge margin in the general elections that year.

Singh was hailed as the architect of India’s economic reforms and the Congress party fielded him in South Delhi, anticipating that his association with the economic liberalisation of the 1990s would resonate with the high-income group in the constituency. The party also believed that Singh’s Punjabi and Sikh background would appeal to the large Sikh and Punjabi population in Delhi.

But Malhotra triumphed against all odds, marking a significant electoral victory and solidifying his place in Delhi’s political landscape.

“During the elections, people like Khushwant Singh and Javed Akhtar campaigned for Dr. Manmohan Singh. The entire corporate lobby was behind him,” Malhotra had said after the elections. “But he didn’t know the nitty-gritty of local politics.”

He said Singh was so deeply affected by the loss, and when some Congress leaders suggested that he fight the 2004 Lok Sabha elections from a safer seat, he politely refused. “He never complained about his loss to me. In Parliament, we always had a very cordial relationship with Dr. Sahib,” Malhotra had said.

Malhotra’s political standing can be gauged from the fact that, in the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, he was the only BJP candidate to win his seat in Delhi, underscoring his deep-rooted support base and influence in the capital.

Overall, the BJP lost the elections under Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s leadership, and L.K. Advani became the Leader of the Opposition. Advani then suggested Malhotra take up the position of Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha.

‘Darling of media’

Before the rise of Arun Jaitley and Sushma Swaraj as prominent Opposition leaders in 2009, Malhotra was regarded as the key pointsperson for all parliamentary activities of the opposition. He was the go-to figure for media briefings and strategy-making within the party, playing a pivotal role in shaping the BJP’s response and approach in Parliament during those years.

He would sit in the Lok Sabha throughout the day, actively participating in discussions and staying fully engaged in the legislative process. After each session, he would make his way to the conference room on the upper floor of Parliament for regular briefings.

A Delhi MP who worked closely with V.K. Malhotra recalled, “One of the best memories of Malhotra in Parliament was his daily briefings, which became irregular during the Modi regime. Without ever being personal or attacking, he would criticise the Manmohan government on facts. After the press conferences, you’d often see him mingling with Congress MPs. He always treated politics as a means of empowerment. Being a professor, his gentle demeanor reflected the early Vajpayee and Nehruvian era of politics. He was a darling of the media as he was always available. From 9 am till late at night, he was always accessible.”

Malhotra’s third high point in his political career came in 2008, when the BJP chose him as the chief ministerial face for Delhi, despite the strong claim by younger leaders like Harshvardhan and Vijay Goel.

The decision went in Malhotra’s favour largely due to his seniority and long-standing contributions to the party, even though it sparked some internal debates.

“Since Advani was at the helm of affairs in the party, he wanted Arun Jaitley to lead the BJP in the Delhi elections against Sheila Dikshit. However, Jaitley, being a sharp politician, was cautious. He realised that if he lost, it could impact his parliamentary career, especially with the Lok Sabha elections just a year away. So, he politely declined the offer. Given the strong rapport between Jaitley and Malhotra since their Delhi University days, it was Malhotra who was chosen to lead the BJP in the election,” said a BJP leader.

However, despite Malhotra’s leadership, Sheila Dikshit’s visible development work played in the Congress’s favour, and the Manmohan Singh-led nuclear deal further bolstered the Congress’s position, he added. “As a result, the BJP lost the elections, though Malhotra managed to win from Greater Kailash.”

Former Union minister Vijay Goel told ThePrint, “Harshvardhan and I were younger, but the party had decided in favour of Malhotra.”

But after Malhotra won from Greater Kailash, the party asked him to continue in the assembly and he had to resign as MP.

When the Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi was planning to make a push for Delhi in 2013, Harshvardhan was chosen as the BJP’s face in the Delhi assembly elections. The party performed well against Arvind Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), but Kejriwal managed to muster support from the Congress and form a government in Delhi.

In 2014, with Modi’s rise to national prominence, he asked Malhotra to take charge as the head of the BJP’s campaign committee in Delhi for the Lok Sabha elections. Despite not being given a Lok Sabha ticket himself, Malhotra worked hard and the BJP won all seven Lok Sabha seats in Delhi that year. Malhotra never complained about not getting the ticket.

After Modi became prime minister in 2014, he appointed several senior party leaders and oldtime Sangh members as governors, but Malhotra was not among them.

“I was offered a position, but I politely declined. I’ve been living in Delhi since before independence, and now I cannot leave the city,” he had said when asked about it.

Malhotra was later assigned a role in sports administration, where he continued to contribute significantly to the development of sports, particularly archery.

Harshvardhan hailed him for his unwavering commitment to ideology.

“Unlike many politicians who publicly display ideological commitment for the sake of power, Malhotra truly believed in it. He was deeply committed to the BJP,” he said.

“In the early days, it was a regular practice for him to personally reach out to any Delhi minister or leader whenever he saw any negative news about the party. He would ask us to look into it, ensuring the party’s image was upheld. Unlike other politicians, he kept a close tab on the party’s daily performance and shortcomings,” he said.

He remembered him as an affable and grounded leader who never shied away from speaking his mind. “Malhotra was one of the early founders of the BJP in Delhi.”

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: I’m neither one to fear nor one to bow down’—Satyapal Malik, one of Modi govt’s fiercest critics