Metamorphosing from a song written by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Vande Mataram became the symbol of protest against the Partition of Bengal in 1905 and soon afterwards caught national imagination as the rallying cry of the freedom struggle, becoming a fixture at Congress sessions before Independence.

On Monday, Parliament will discuss Vande Mataram for 10 hours on the occasion of its 150th anniversary, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi set to initiate the debate on the government’s behalf. The song, which was partly written in Sanskrit and partly in Bengali, was composed in 1875 and included in Chattopadhyay’s novel Anandamath in 1881 during its serialisation in the magazine Bangadarshan. During the 1896 Congress session in Calcutta, Rabindranath Tagore set it to tune and sang it for the first time.

The widespread use of the song — Vande Mataram means “Mother, I bow to you” — began only after it captured popular imagination during the movement against Lord Curzon’s Partition of Bengal of 1905. It transcended the province, with the use of Sanskrit making it relatable in large parts of the country. There was also a suggestion at the time that the word saptakoti, or seven crores, the population of united Bengal at the time, be substituted with trimshatkoti, meaning 30 crores, the estimated population of India at the time, to adapt the song as one symbolising the Indian freedom struggle.

Anandamath, published as a book in 1882, tells the story of a rebellion of sanyasis (Hindu monks) against Muslim conquerors. The song appears in the novel when Mahendra, a householder, meets Bhavananda, a fighting monk, who sings the first few lines. A curious Mahendra then seeks to know who this mother was, but Bhavananda sings the next few lines instead of answering. When a perplexed Mahendra tells the monk he is singing about the country, not a mother, Bhavananda responds, his eyes welling up with tears, “We know no other mother… except the land that gave us birth.”

Even as the song acquired rapid popularity because it represented the zeal to free the country, it got mired in controversy. Objections began to emerge from sections of Muslims that it was an invocation to a Hindu goddess. The Congress Working Committee (CWC) stepped in and adopted a lengthy resolution in October 1937, R K Prabhu writes in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee and the Vande Mataram Song that is available at the Prime Minister’s Museum and Library (PMML).

The resolution said that since the song was composed before Chattopadhyay’s book was written, it should be considered separate from it. “The song and the words ‘Vande Mataram’ were considered seditious by the British government and were sought to be suppressed by violence and intimidation. At a famous session of the Bengal Provincial Conference held in Barisal in April 1906, under the presidentship of Mr. A. Rasul, a brutal lathi charge was made by the police on the delegates and volunteers … Delegates were beaten so severely as they cried ‘Vande Mataram’ that they fell down senseless,” the resolution said. “Since then, innumerable instances of sacrifice and suffering all over the country have been associated with ‘Vande Mataram’ and men and women have not hesitated to face death with that cry on their lips.”

It added, “Gradually the use of the first two stanzas of the song spread to other provinces and a certain national significance began to attach to them. The rest of the song was very seldom used and is even now known to few persons. These two stanzas described in tender language the beauty of the motherland and the abundance of her gifts. There was absolutely nothing in them to which objection could be taken from the religious or any other point of view … Indeed the reference in it to thirty crores of Indians makes it clear that it was meant to apply to all the people of India. At no time, however, was this song, or any other song, formally adopted by the Congress as the national anthem of India. But popular usage gave it a special and national importance.”

The CWC, the resolution said, felt “that past associations, with their long record of suffering for the cause, as well as popular usage, have made the first two stanzas of this song a living and inseparable part of our national movement and as such they must command our affection and respect”.

It added, “There is nothing in these stanzas to which any one can take exception. The other stanzas of the song are little known and hardly ever sung. They contain certain allusions and a religious ideology which may not be in keeping with the ideology of other religious groups in India.”

“The Committee recommends that wherever ‘Vande Mataram’ is sung at national gatherings, only the first two stanzas should be sung, with perfect freedom to the organisers to sing any other song of an unobjectionable character, in addition to, or in the place of, the ‘Vande Mataram’ song,” it said.

When the question of the choice of the national anthem came before the Constituent Assembly, Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana was chosen over Vande Mataram, with Nehru explaining in a note to the Cabinet on May 21, 1948, that Jana Gana Mana was more amenable to orchestral rendering than Vande Mataram, which was “deeply respected” by Indians. He said except for the Governor of Central Provinces, the other Governors also had the same opinion.

Vande Mataram and Hindutva

Former nominated Rajya Sabha MP Swapan Dasgupta wrote in his book Awakening Bharat Mata that sections of Muslims saw the song as idolatrous and “anathema to Islam”, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah seeing it as a “hymn to spread hatred for the Musalmans”.

Dasgupta underlined the reverence for the song in the Sangh Parivar: “In the annals of Hindu nationalism, the story of Vande Mataram from being the icon of the national movement to becoming an extra… epitomised betrayal and a distortion of nationhood. For all those associated with the RSS parivar and the BJP, continuing attachment to Vande Mataram – without, at the same time, undermining the importance of the national anthem – has become an article of faith.”

Dasgupta said it was customary to sing the whole song, and not just the first two stanzas, at Sangh events, and recalled the slogan, often used by the Sangh’s student wing ABVP: Bharat Main Yadi Rehna Hai To, Vande Mataram Kehna Hoga (If you have to live in India, you have to chant Vande Mataram).

Dasgupta said the Muslim opposition to the song put the Congress in a quandary, as the Congress under Nehru, and even later, was increasingly trying to be seen as “secular” and shed all Hindu imagery. “In the process, it vacated a space that was gleefully appropriated by Hindu nationalism as its very own,” Dasgupta wrote. “The slow transition of Vande Mataram and Bharat Mata from being a mainstay of the Congress to becoming identified with the BJP epitomised this shift.”

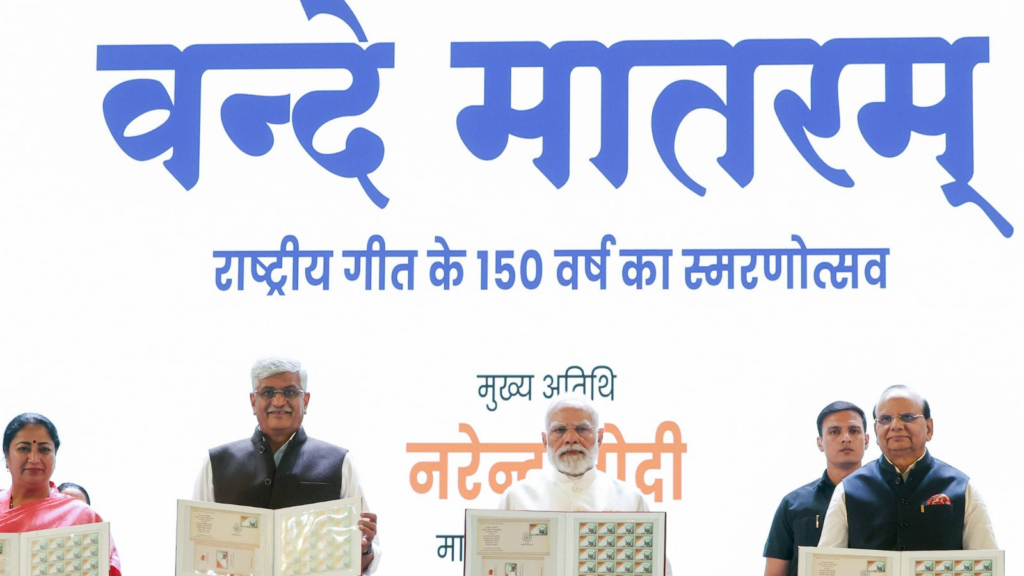

Last month, at the inauguration of the year-long celebrations to commemorate 150 years of ‘Vande Mataram’, Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke about important stanzas dropped from the national song in 1937, how the song “was broken and cut into pieces”, and that “its division sowed the seeds of the division of the nation and divisive politics, which remains a challenge”.

The Opposition responded sharply, claiming that Modi had “insulted” Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore and members of the Congress Working Committee of 1937 — including Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Patel, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Rajendra Prasad, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Sarojini Naidu among others — who suggested the removal of the verses to make the song more inclusive and not hurt religious sentiments.