In the shadowy depths of a cave in northern Thailand, biologists have uncovered a new chapter in the story of Earth’s biodiversity. Two vibrant, spiny millipedes, unlike any seen before, have been formally described by researchers. Their dragon-like appearance and hidden habitat sparked immediate scientific curiosity. But beyond the spectacle, the discovery opens new questions in genetics, adaptation—and perhaps even astrobiology.

From Cave Shadows To Scientific Spotlight

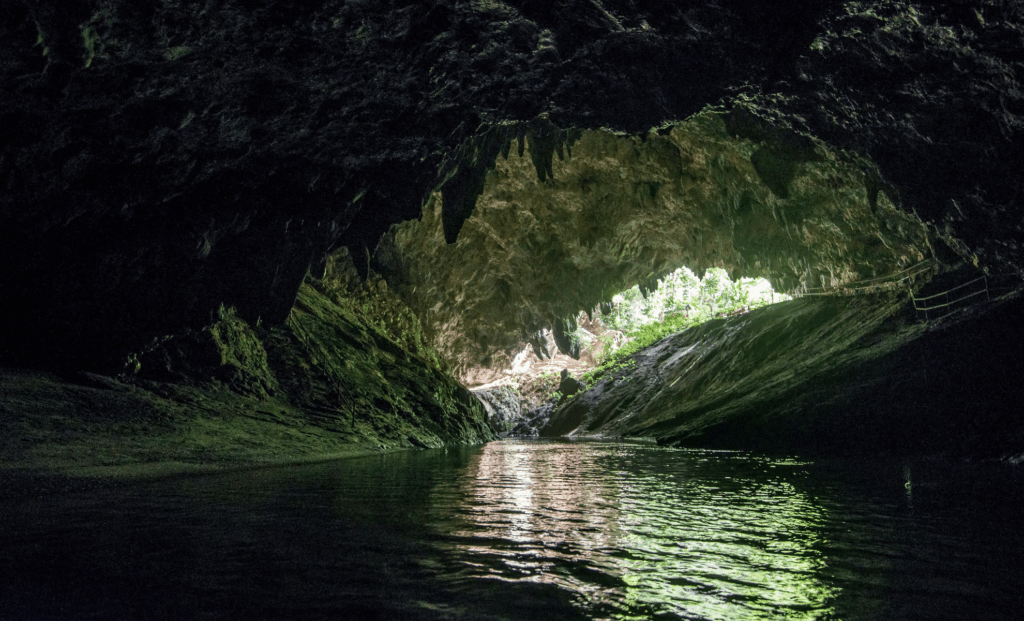

Thailand’s caves have long been a refuge for some of the planet’s most enigmatic species, but few discoveries have stood out quite like Desmoxytes millipedes. In a recent paper published in the journal Tropical Natural History, researchers described not just one, but two new species from the Desmoxytes genus, known for their bright coloration and striking exoskeletal spines. These organisms were located in two separate limestone caves in northern Thailand, environments known for their isolation and extreme ecological constraints.

The newly described species—Desmoxytes rubra and Desmoxytes chamberlini—have evolved extraordinary features, from vivid pigmentation to elongated body segments resembling the back ridges of mythical dragons. Their adaptations seem tailored to pitch-black, resource-scarce cave environments, and the millipedes’ exaggerated body forms may be driven more by evolutionary signaling than defensive function. The study notes that these creatures are likely endemic, found only in these limited subterranean zones, raising urgent questions about conservation, biogeography, and cave ecosystem fragility.

Evolution Written In Red And Black

The evolutionary pressure cooker of isolated caves often produces lifeforms that seem almost alien. In the case of these millipedes, their flamboyant traits—a deep red exoskeleton, defensive chemical secretions, and an almost weaponized body form—appear to serve little purpose in complete darkness. So why evolve to look like a dragon?

One possible explanation lies in evolutionary inheritance rather than current function. These features might have once served a purpose in above-ground ancestors and persisted due to genetic drift. Alternatively, even in caves, brief encounters with predators or competitors at cave mouths might still favor bold chemical and physical defenses. Interestingly, the study notes that Desmoxytes chamberlini shares traits with other members of the Desmoxytes “dragon” group, pointing to an ancient lineage now splintered by geography and cave isolation.

Comparative studies across the Desmoxytes genus, especially involving their genetic blueprints, may also shed light on how rapidly or slowly speciation occurs in cave ecosystems. And that could provide broader clues for understanding how life evolves in extreme, closed environments—not just on Earth, but possibly on other planetary bodies with subsurface biomes.

Genetic Goldmines And A Link To Astrobiology

What makes these millipedes particularly interesting to biologists isn’t just their looks—it’s their genetic adaptability. The researchers believe that these species hold potential keys to understanding how genetic drift, isolation, and environmental stressors shape complex traits. And these lessons aren’t just terrestrial.

Extreme environments like the caves of Thailand are increasingly being viewed as analogs for potential extraterrestrial habitats, such as subsurface tunnels on Mars or Europa. Studying how life persists and diversifies in near-total darkness, with limited resources and few external influences, can help scientists model what alien ecosystems might look like—and how we might one day recognize signs of them.

This doesn’t mean millipedes will guide us to Martian microbes. But the principles behind their evolution—resilience, specialization, and morphogenetic novelty—are exactly what astrobiologists are beginning to prioritize.