HYDERABAD, India — Sai Jagruthi, a 17-year-old engineering student at a giant technical university in the south Indian city of Hyderabad, remembers exactly where she was when she heard the news.

She had just finished a dinner of okra and rice in the student cafeteria, she said, when her father called to tell her about a proclamation President Donald Trump had made from the White House on Sept. 19. Every H-1B visa, a work permit that has brought millions of Indians to the United States since the 1990s, would now come with a $100,000 fee. “My dreams were shattered,” she said.

She recalled her father saying, “‘It was the best option, and we are going to lose it.’” For Jagruthi, excelling at her studies was a family affair. Her father, who works at a bank, “wants a better life for their daughters than his own. Going to the U.S. was a ticket to that,” she said.

The new rules threaten to stop up a pipeline for a fast-growing class of young dreamers. Indians with middle-class backgrounds, especially in the country’s relatively prosperous south, have invested deeply in technical education as a way to get ahead — a way that often went through the United States.

Trump is reordering U.S. immigration policy, vowing to make it increasingly difficult for many foreigners to enter and remain in the country. The order that struck Jagruthi so directly concerned a category of visa that Indians dominated: 72% of the 400,000 H-1Bs granted last year went to applicants from India.

Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, a public school where Jagruthi is enrolled along with 450,000 other students, is full of young people with similar dreams. Its registrar estimated that 20% of its graduates seek advanced study in the United States, especially American master’s degrees that qualify them for H-1Bs.

A classmate of Jagruthi’s in the mechanical engineering department, Ruthvitch Sharma, said he thinks everyone in his shoes harbors a similar ambition: “to work with the greatest talents in the world.” For him, with his passion for heat transfer technology, that means working at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Right after the White House attacked the H-1B visa as a “deliberately exploited” program and imposed a fee higher than the average visa holder’s first-year salary, it backpedaled, saying the $100,000 would apply only to applications for new visas. Days later, a federal agency proposed scrapping the annual lottery for new visas in favor of a system that gives priority to the highest-paid applicants.

The changes are expected to force companies, which typically pay much of the cost of an H-1B visa, to hire fewer foreigners and to be choosier about whom they hire. That could, in turn, create demand for American workers and push up wages.

The new policy plunked another complication into already difficult U.S.-India trade negotiations. The sudden swings in how it was introduced created deep confusion among potential visa-seekers. And it made one thing clear to the students in Hyderabad: The way forward, insofar as it depends on the United States, is in jeopardy.

Going to America isn’t the only option. Germany, China and Canada have been quick to propose themselves as alternatives. What’s more, many Indians, including some students, think there may be benefits to starting their careers at home and ending the brain drain to the United States.

The new rules are plainly awful, however, for companies such as Tata Consultancy Services, which sends thousands of Indian nationals to the United States on assignment. Its stock has lost $50 billion since Trump’s announcement.

For young Indians striking out in their careers, the sense of a betrayal was clear.

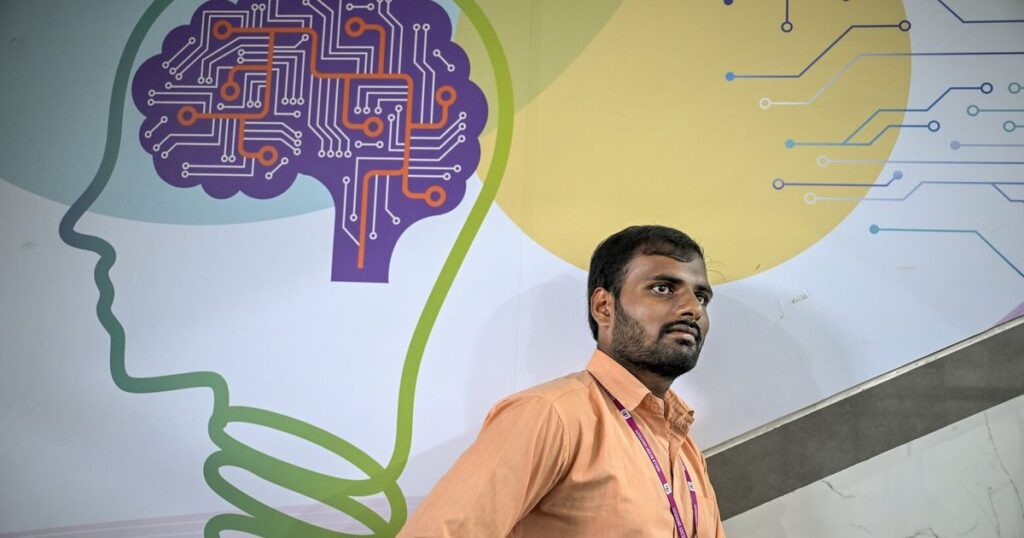

Santosh Chavva, 21, is an undergraduate in the final year of his degree in artificial intelligence. He was already sifting through graduate programs in the United States. “But then a bomb fell. Trump announced the H-1B visa hike, which was such a shock to me,” he said. His aunt, working in Chicago for the past 15 years, warned him that an expensive American degree, without access to an American salary to compensate it, could push him into a debt trap.

“I felt so sad,” he said. For some families, it could also break the bank.

Chavva is a student at Malla Reddy University in Hyderabad, one of the private colleges that have sprung up in the Telugu-speaking parts of south India.

A family like Chavva’s — his father works for a pharmaceutical company — could spend $34,000, or about three years of savings, to pay for his first degree at an Indian university. On top of that, tuition at an American master’s program, undertaken on a student visa with an eye to earnings on an H-1B, would cost the family another five or six years in savings.

Chavva’s classmates expressed frustration that the changes would harm both countries. The American business world is chock-full of executives, engineers and business owners who got their start on H-1Bs.

“They built a lot of unicorns and startups,” said Narra Lokesh Reddy, who had wanted to earn an American master’s degree before Trump unveiled his new rules. More hopefully, Reddy said, forcing India’s potential entrepreneurs to stay at home might “push India to self-reliance.”

The Indians who already have an H-1B visa are worried, too.

Some of them were celebrating their personal good fortune by walking in circles around the center of a famous temple in Hyderabad, the Chilkur Balaji, not far from an American consulate. One man, a 31-year-old father who lives in Plano, Texas, was circling an idol of the god Balaji 108 times in thanks. His three-year H-1B had been extended earlier that morning. He only talked to us if we agreed not to identify him, worried about saying anything that could jeopardize his visa.

Another visa holder marking her good fortune at the temple, who also did not want her surname used, had along with her husband recently won lotteries for F-1 and L-1 visas while home in Hyderabad on a break. The couple plans to move to Seattle, where she has a job.

Jagruthi at Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University consoled herself that she still had options.

“I will consider Germany once my studies are over here,” she said. “If the U.S. does not work out, I will try that.”

The head priest at Chilkur Balaji, C.S. Rangarajan, keeps abreast of worldly matters affecting his flock. It’s not all about H-1B visas, he emphasized, calling for a show of hands to demonstrate that only a tiny number of the temple goers had come to pray for visas. Their god, a form of Vishnu, answers prayers of all kinds, he said, like bringing babies to newlyweds. He urged them to focus on the bigger picture.

“Trump is here for a few years, Balaji is forever,” Rangarajan said.

In the meantime, there are Germany, Canada, and other countries to explore.