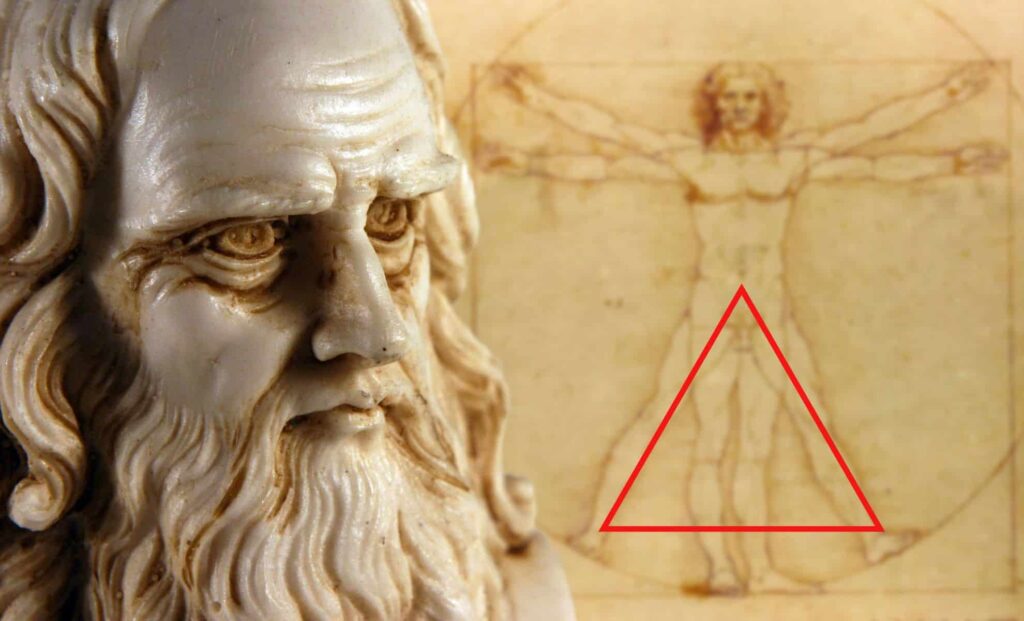

The discovery centers on a discreet equilateral triangle located in the figure’s lower anatomy. This simple form may provide a new explanation for the precise mathematical relationship between the square and the circle that define the iconic proportions of da Vinci’s famous sketch.

Drawn around 1490, the Vitruvian Man has long been admired as a symbol of symmetry and harmony. It visually represents the Renaissance idea that the human body mirrors the proportions of the universe. But despite its fame, scholars and mathematicians have struggled to reverse-engineer da Vinci’s construction method.

While many assumed the artist used the golden ratio, the actual measurements don’t quite align. Now, Mac Sweeney’s research introduces an alternative framework grounded in both geometry and anatomy. Published in the Journal of Mathematics and the Arts and reported by ScienceAlert, his study puts forward a specific numerical ratio, 1.64 to 1.65, that reflects a deeper pattern found in nature and biology.

A Triangle Hidden in Plain Sight

Leonardo da Vinci left a textual clue in his notebooks, noting that when a person raises their arms and spreads their legs, the space between the legs forms an equilateral triangle. Mac Sweeney took this observation seriously and used it as a geometric starting point. His measurements, drawn from the original drawing, identified a triangle extending from the crotch to the spread feet, producing a ratio close to 1.64:1 when compared to the height of the navel.

This figure stands near the tetrahedral ratio of 1.633, a number that describes optimal spatial arrangements, such as the packing of spheres in a pyramid shape. According to Mac Sweeney, this connection is not coincidental. “The solution to this geometric mystery has been hiding in plain sight,” he stated in ScienceAlert. The paper argues that the equilateral triangle was more than an artistic flourish; it was Leonardo’s method for calculating the complex relationship between static and dynamic human postures.

Echoes of Dental Anatomy

Mac Sweeney’s professional background as a dentist helped him notice an anatomical parallel. The triangle in da Vinci’s drawing mirrors Bonwill’s triangle, a geometric model used in dentistry since 1864. This structure connects two jaw joints to the midpoint between the lower front teeth and is considered foundational to understanding optimal jaw function.

According to Mac Sweeney’s findings in Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, Bonwill’s triangle and da Vinci’s triangle share not just shape but also proportions. The ratio between the sides of the square and the radius of the circle in the Vitruvian Man aligns closely with the values seen in both human cranial architecture and Bonwill’s dental measurements, again hovering near the 1.64–1.65 range.

This connection suggests that da Vinci might have arrived intuitively at principles that later became essential to fields like dental prosthetics and jaw mechanics. The artist’s intricate knowledge of anatomy, demonstrated in hundreds of anatomical sketches, may have informed his geometric constructions in more precise ways than previously acknowledged.

Convergence of Geometry and Biology

Throughout the analysis, Mac Sweeney emphasizes a recurring theme: that Leonardo da Vinci may have discovered a geometric constant appearing across biological systems. The 1.633 ratio, tied to tetrahedral geometry, shows up in optimal sphere packing, crystal structures, and, as recent anatomical research suggests, human cranial proportions.

As stated in the study, modern anatomical data confirm that human skull architecture consistently exhibits this ratio, with measurements of cranial arcs falling within a range of 1.64 ± 0.04. These parallels imply that da Vinci’s famous figure could encode a deeper structural truth, not just about human beauty or aesthetics, but about how bodies are organized according to mechanical and spatial efficiency.