When a song becomes a national anthem, it is immediately elevated in stature to hold an exceptional public status.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the protocol, the do’s and don’ts that govern its performance. However, as Peter McDonald, a Professor of English and Related Literature at the University of Oxford, has noted, the “anthemisation” process often strips a song of its artistic essence — and at times, even its original political context — irrevocably transforming both its meaning and form.

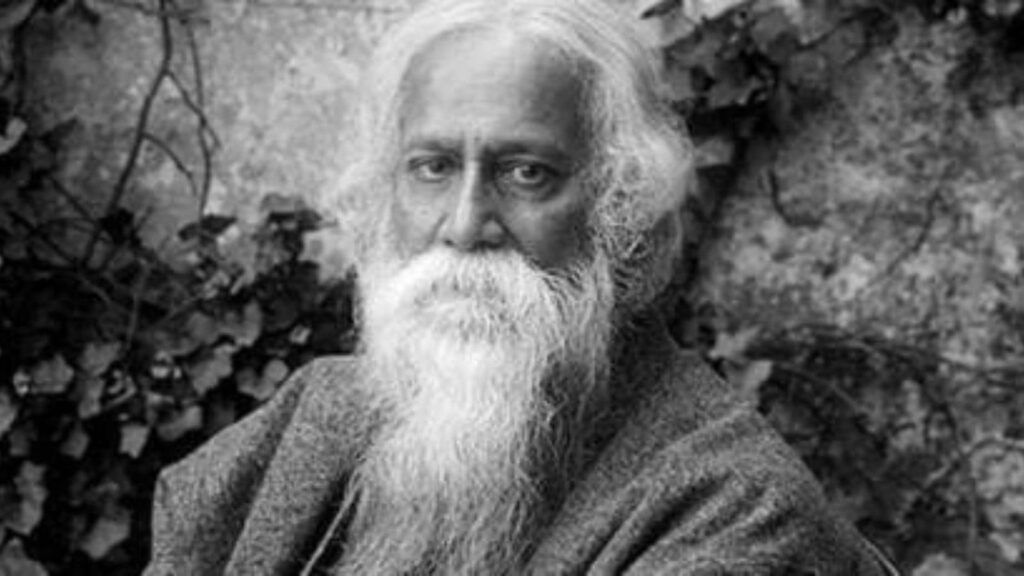

This deeply political distinction between a song and an anthem is at the heart of a recent controversy over Rabindranath Tagore’s song Amar Shonar Bangla (My Golden Bengal). At a Congress Seva Dal event in Assam’s Sirbhumi district, 74-year-old Bidhu Bhushan Das hummed two lines of the song before making his speech. Later, he found himself embroiled in a political row as CM Himanta Biswa Sarma of the BJP accused the Congress of performing the “national anthem of Bangladesh”.

Originally composed in 1905 as a visceral response to the British trying to divide Bengal, its largest administrative province, along religious lines, the song became the anthem of newly liberated Bangladesh in 1972. The song, be it in its original form or in its “anthemised” one, is rooted in politics, but the nature of the politics rapidly changed in the intervening decades.

In July 1905, the British viceroy, Lord Curzon, announced the partition of Bengal, saying it was too large to be effectively administered. Consequently, Bengal was to be split between a Muslim-majority east and a Hindu-majority west. The announcement was immediately met with massive outrage, especially among the Hindus of Calcutta, who saw it as an attempt to split the Bengali-speaking community. It sparked the Swadeshi movement, a campaign to boycott British goods and embrace Indian-made products. Rallies, meetings, songs, and writings criticising the British decision became common at the time. Unable to tame the protests, the British were forced to go back on their decision and reunite Bengal in 1911.

It was in this atmosphere of widespread discontent that Tagore wrote Amar Shonar Bangla. The song begins as a deeply romantic, poetic celebration of Bengal’s landscape. As the English translation of the lyrics goes:

“My Bengal of gold, I love you.

Forever, your skies, your air set my heart in tune,

As if it were a flute.

In spring, o mother mine,

The fragrance from your mango groves

Makes me wild with joy,

Ah, what a thrill!

The first couple of stanzas, deeply evocative in their reverence for Bengal’s landscape, became Bangladesh’s anthem. McDonald told The Indian Express that “the final line of the second verse, which is part of the anthem, registers the pain of the British partition of 1905 in oblique and understated ways”. It hints at the dark period of Bengal’s history in which the song was born and also makes the celebratory affirmation of the landscape in the first verse so important.

“If sadness, oh mother mine, casts a gloom on your face,

My eyes are filled with tears!”

The more polemical and political aspects of Tagore’s original composition, though, do not make their way to the anthem. McDonald noted that the final lines of the song allude directly to the boycott of foreign goods — “a hanging rope disguised as a crown” — that underpinned the Swadeshi movement.

Tagore’s own views on Swadeshi underwent a profound change in the ensuing years. In a series of essays written between 1905 and 1908, he expressed doubts about the efficacy of the Swadeshi approach. The boycott of foreign goods, he realised, was not enough. What was necessary was a constructive programme for self-empowerment or “atma-shakti”. His views criticising Swadeshi found their most powerful expression in his celebrated 1916 novel Ghare Baire (The Home and the World).

Further, his views on nationalism would also undergo a dramatic transformation in the years since 1905, culminating in the lecture series of 1917 that was later published as Nationalism. One of the biggest issues he had with nationalism as an anti-colonial project was that it mirrored the worst aspects of European political thought. And so to adopt nationalism to fight imperialism meant imitating the very forces one sought to resist, Tagore held.

His forceful critique of nationalism would appear to read almost paradoxical in the context of his earlier writings celebrating Bengal, which can come across as a form of “Bengali nationalism”.

Professor Tista Das, who teaches the history of 19th-century Bengal at Bankura University in West Bengal, said Tagore’s writings on Bengal were not about a nationalism of the exclusionary kind that emerged later in the 20th century. Rather, Das said, his nationalism must be seen in the context of the times in which he was writing, in this case, the 1905 Partition. His celebration of Bengal was rooted in cultural pride, attachment to its lush physical landscape, and humanism, according to her.

McDonald does not see Tagore’s Bengali nationalism as paradoxical. “Most of his early writings are typical of 19th-century romantic nationalism anywhere in the world,” he said, comparing the poet’s early works to those of the Brothers Grimm and W B Yeats, who also found a sense of national identity in the folk traditions of Germany and Ireland, respectively. Tagore, however, evolved and changed his views on recognising the connections between imperialism and nationalism.

The politics of the land changed, as did the poet, and in the years to come, his song too transformed into an anthem. Ironically, a song that Tagore wrote to call for the unity of Bengal became the anthem of a nation born out of its division. More ironic still is the uproar the song has sparked in the land of its birth, the same land that venerates the Nobel laureate by adopting another of his songs as its national anthem.