The newly appointed chief minister immediately rang up the district magistrate (DM) and instructed him not to file an FIR. Stunned, the DM protested: “Sir, this is a question of the state’s prestige. How can we tolerate this?”

Thakur responded calmly: “DM Saheb, you can save the father of the chief minister. But what about the thousands of such fathers who are beaten every day without the administration’s knowledge? Time will settle these questions. It is a slow process.”

Almost half a century after he served as chief minister for just two years and three months (December 1970 to June 1971 and June 1977 to April 1979), Thakur remains alive in not just the rhetoric of Bihari politics, but in its very essence.

As Bihar heads for a critical assembly election on 6 and 11 November, political parties across the state are claiming his legacy in a bid to bolster their chances in the polls.

Last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi began his Bihar election campaign from Karpoori Gram, invoking the legacy of the socialist icon, who his government posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna last year.

“I went to Karpoori Gram before coming here,” he said in Samastipur. “I got a chance to pay my tributes to him. It is due to his blessings that people like me and Nitish ji, coming from backward and poor families, are on this stage. In independent India, in attempts to bring social justice, his role was very big. We had the good fortune of awarding him Bharat Ratna. He was our inspiration.”

Meanwhile, even before Modi set foot in Bihar, the Congress attacked the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) alleged hypocrisy regarding Thakur.

“Is it not an acknowledged fact that the Jan Sangh—from which the BJP emerged—brought down Karpoori Thakurji’s Govt in Bihar in April 1979 when the-then CM introduced reservations for OBCs? Is it not a fact that Karpoori Thakur ji was subjected to the vilest abuse by RSS and Jan Sangh leaders then?” Congress leader Jairam Ramesh asked on X.

In recent years, Thakur’s legacy has been retrieved from the footnotes of history and become a contested ground among Bihar’s political rivals, each claiming succession to a trite, reductive version of his story—one that paints a feel-good portrait of a man who rose from humble beginnings, remained an uncompromising idealist, and fought as an unflinching caste warrior.

‘Lohia in action’, ‘socialist of the soil’, the ‘original subaltern hero’ and ‘jan nayak’—sobriquets given to him are regularly relayed glibly by news channels.

Anecdotes highlighting his “simplicity”—like wearing a tattered coat borrowed from a friend on a trip to Yugoslavia, which prompted Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the then-President of Yugoslavia, to gift him a coat—are recounted repeatedly, often stripping his politics of a nuanced analysis.

Yet, Thakur’s concrete contributions to shaping a distinctly Indian brand of socialism, his unwavering commitment to reservations even at the cost of his governement, his failure to forge a seamless, contradiction-free politics of the backwards, and his eventual political isolation—captured in his own lament that he would not have been humiliated had he been a Yadav—remain largely neglected in both popular and academic accounts of heartland politics.

From Lalu Yadav’s popular slogan, Vikas nahi, samman chahiye, to Nitish Kumar’s ‘quota-within-quota’ politics, from the Modi government’s controversial push for Hindi to its introduction of reservations for the economically weaker sections (EWS) or Rahul Gandhi’s promise to remove the 50 percent cap on reservations, Karpoori Thakur’s silent imprint on both state and national politics is unmissable.

As journalist Santosh Singh and researcher Aditya Anmol argue in The Jannayak: Karpoori Thakur, Voice of the Voiceless, he “is the foundation stone who is not visible but still holds the entire edifice”.

As Bihar goes to polls and every major contender claims to be the most fitting successor to his legacy, ThePrint explains Karpoori Thakur’s political legacy.

Also Read: Karpoori Thakur’s politics of social justice cost him CM post. But he wasn’t power-hungry

‘Karpoori, the camphor that fills the air with aroma’

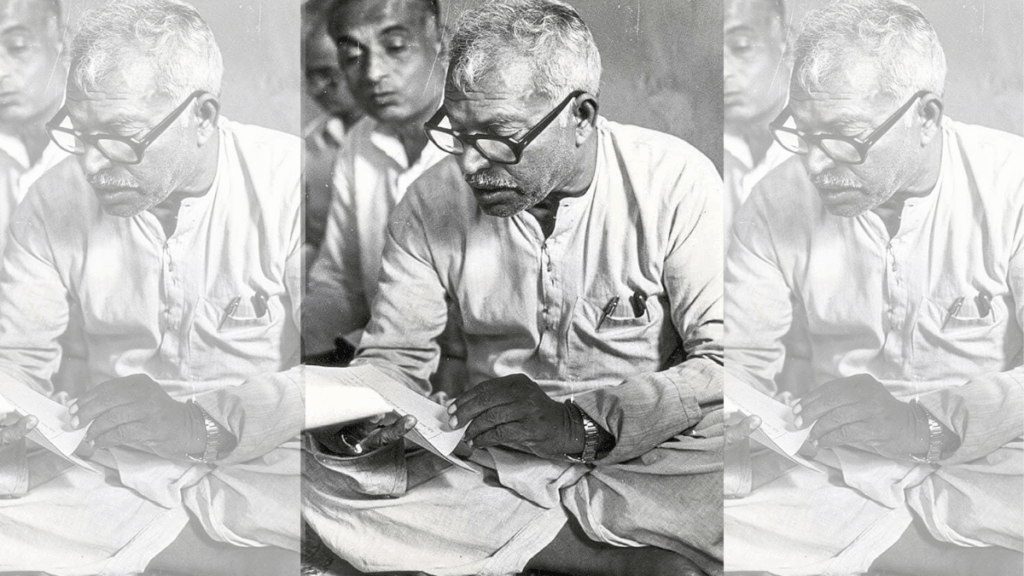

Thakur was born on 24 January 1925 in Pitaunjhia in the Nai, or barber, caste. Named Kapoori at birth, his fate was supposedly sealed. He was, his parents thought, going to be like his many ancestors, a barber.

But the young boy’s commitment to his studies was unwavering.

Gokul Thakur, who was initially reluctant to make his boy study, had to eventually concede. For years, he walked 16 km a day to his school in Tajpur.

Eventually, when he finished class X, Gokul was ecstatic. “Hamro Kapoori matric pass hoy gelay, malik (Master, my son has passed Class 10),” he went to tell the village landlord.

“Good,” the landlord replied nonchalantly. “Pair dabao (Massage my legs),” he then told Kapoori, who obliged.

By the late 1930s, the young Kapoori was already a bit of a star at school.

When the socialist leader Pandit Ramnandan Mishra was invited to speak at a function in the auditorium of Krishna Talkies at Samastipur, students and teachers prodded Kapoori to represent their school on stage.

He spoke extempore to a rapt audience. An impressed Mishra told him, “You are not Kapoori, you are Karpoori. You are the camphor that fills the atmosphere with its overpowering aroma.”

In the years that followed, Karpoori continued to demonstrate his academic and intellectual brilliance.

But, as Singh and Anmol argue, he was born into a world of revolutions. “He was cradled amidst a plethora of ideologies, nurtured by messages from the Russian Revolution, the Indian freedom movement, the socialist movement, and the Kisan Andolan (farmers’ movement),” they write.

Socialism, communism, capitalism, dialectical materialism, Hegel, Marx, Indian philosophy, bourgeois policy, and the origins of family, society and property — Karpoori was consumed by the world of ideas and politics.

Quietly, the young boy found himself irrevocably drawn to his lifelong calling: politics.

By 1952, as independent India prepared for its first general election, Karpoori was already a young socialist leader—one who had spent 25 months in jail and earned the respect of figures like Jayaprakash Narayan.

When the first election came, a hesitant Karpoori was persuaded by Socialist Party veterans to contest from Tajpur, a constituency dominated by OBCs, Yadavs and Kushwahas.

Karpoori, who belonged to the politically insignificant Nai caste, which constituted about 1.5 percent of the population, barely stood a chance.

But at a time that the Congress was nearly undefeatable—it won 285 of the 330 seats in Bihar’s legislative assembly, and 47 of the 55 Lok Sabha seats—Thakur won, and became an MLA.

The legislator and the minister

From his first years as an MLA, he shaped a distinct brand of Indian socialism through his interventions inside and outside the assembly.

He spoke of prioritising jobs for Hindi-speakers and replacing the British-era civil services with an economic service, whose officers would be well versed with villages.

He would make sharp connections between communalism and capitalism, and would quote extensively from the Ramayana and The Discovery of India with equal ease.

Within the Secretariat, he waged other battles, like turning an “only for officers” lift into one used by everyone. On the streets, he routinely led powerful mass movements.

By 1967, the Congress government in Bihar was gasping for breath. It was beleaguered by casteism and corruption. Two successive drought years had devastated whatever credibility was left.

Slogans created by Thakur filled Bihar’s air with revolutionary optimism: Congressi raj mitana hai, Socialist raj banana hai (We have to end Congress rule and bring in Socialist rule), Angrezi me kaam na hoga, phir se desh gulam na hoga (We won’t work in English, the country won’t be a slave again), and Rashtrapati ka beta ya chaprasi ki santaan, Bhangi ya Brahman ho, sabki shiksha ek samman” (Whether it’s the son of the President or a lowly peon, whether it’s a sweeper or a Brahmin, let everyone have equal access to education).

Yet, there was one slogan that defined Thakur, Bihar and north Indian politics like no other: Sansopa ne baandhi gaanth, pichhda pawe sau me saath (SSP, the Samyukta Socialist Party, has pledged to provide 60 per cent reservation to OBCs).

From here on, Bihar and, eventually, north Indian politics came to be divided perpendicularly between the Forwards and the Backwards.

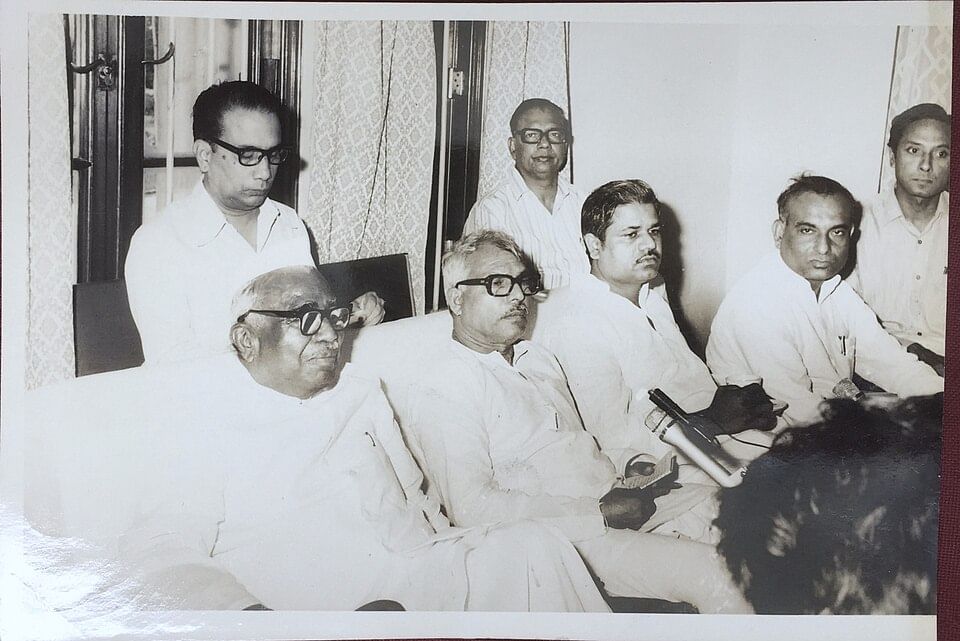

In 1967, the first non-Congress government came to power in Bihar. Thakur, then the most popular socialist leader in Bihar, became the deputy chief minister, while Mahamaya Prasad Sinha, a Kayastha, became the chief minister.

Yet, it was a government whose deputy CM was consistently more popular than the CM.

It was during his tenure as deputy CM and education minister that Thakur sought to democratise education by removing English as a compulsory subject for matriculation.

English was not just a ticket to jobs, but also to a seat on the high table in Bihar. It was a time when English speakers would be hired by hosts to attend wedding parties, so that their English-speaking guests would take them seriously.

Thakur’s removal of English as a compulsory subject, therefore, was a radical move. After 1967, the number of Dalits and Backward castes passing class X surged. It was, in fact, a number of these students who would form the bedrock of the JP movement just years later.

The move was naturally met with contempt by the elite, who disdainfully called it “Karpoori Division” or “PWE (Pass without English)”.

At a function in Bhagalpur, a professor sarcastically said that Thakur removed English as a compulsory language because he might have been “weak” in it. Thakur then went on to deliver his speech, which was prepared in Hindi, in English to demonstrate that “English is just a language and not a certificate of being knowledgeable”.

In 1970, when he became chief minister briefly, he strictly implemented the Official Language Act and made it mandatory to use Hindi for all official communication. The use of English, he said, was preventing people from experiencing democracy.

Also Read: Karpoori Thakur removed burden of English. Then came a surge of backward caste college students

Mandal before Mandal

When the Emergency was lifted in 1977, Thakur became chief minister once again, a tenure that would come to define his legacy.

The day was 3 November 1978. Morarji Desai, who was prime minister at the time, was delivering a powerful speech at Patna’s Gandhi Maidan. In the speech, Desai made some remarks against reservations.

A section of the crowd cheered loudly, while Thakur quietly looked on. He then duly escorted the PM to the airport and drove straight to the secretariat. By 8.30 pm, Thakur issued a notification for reservations for the backwards.

Implementing the recommendations of the Mungeri Lal Commission, Thakur announced 20 percent reservations in addition to the existing 24 percent reservation for SCs and STs. Of this, 12 percent was to be for the Most Backward Castes (MBCs) and eight percent quota for the remaining OBCs.

Bihar was up in flames. Thakur faced opposition from upper-caste members of his own government. Students of elite colleges took to the streets, burning buses and shouting slogans against what they saw as an assault on merit.

Overnight, for the elite, Singh and Anmol write, Thakur turned from the jan nayak (people’s leader) to the khalnayak (villain). Abusive slogans against Thakur reverberated across the state: Ye aarakshan kahan se aayi, Karpoori ki mai biyayi (Where does this reservation come from, Karpoori’s mother has perhaps given birth to it); Karpoori-Karpura, chhod gaddi, pakad usutra (Down with you, Karpoori, you better quit your throne and take up your razor).

Riots followed. But they were not just about jobs. They marked the beginning of a new social order.

As political scientist Harry Blair wrote, “The whole struggle is not really over the 2,000 jobs; rather, the reservation policy is a symbolic issue and has gripped the imagination of virtually everyone in Bihar who has even the slightest degree of political awareness.”

“Through the reservation issue, Karpoori Thakur asserted that the Backwards had displaced the Forwards as the dominant force in Bihar politics, that the old days of dominance in public affairs from village to Vidhan Sabha by the twice-born were gone forever, and that his government would be the one based on the support of the Backwards,” he added.

Under pressure from within the Janata Party, Thakur negotiated a revision with party president Chandra Shekhar. The final formula, promulgated through a government order on 10 November 1978, reserved 20 percent of posts in the state civil services and professional colleges for OBCs (restricted to those not paying income tax), 3 percent for women and 3 percent for “economically backward” upper castes.

The order triggered another wave of protests across Bihar, far more widespread and violent. The polarisation between “Forwards” and “Backwards” quickly spread from the streets to the countryside.

“After 1978, neither side saw the conflict as amenable to compromise,” American political scientist Francine R. Frankel wrote in the book, Dominance and State Power in Modern India.

“The Forwards, for their part, had already experienced an erosion of social prestige, economic affluence, and political power at the villages,” she writes.

“Even so, their resistance to admitting Backwards could not be explained solely on economic grounds. Caste feeling was ‘in the blood’; they were not prepared to give up what seemed to them their rightful privilege to rule.”

Meanwhile, the leaders of the Backward Classes, “shocked into recognition of the caste prejudice that still prevented their rise to the top rungs of the occupational ladder, became convinced that only the displacement of the Forward Castes from positions of power could open up opportunities for social mobility”.

As Bhola Prasad Singh, a Kurmi MLA, said at the time, the ultimate purpose of the Backward Classes movement was the destruction of the caste system “by using poison to remove poison”.

Thakur, who had hitherto been a mass leader with an appeal across social groups, was reduced to being a leader of the Backwards only.

But he remained unmoved. “Those against me are casteists of the first order,” he told India Today in an interview.

Yet, the move cost him his government. In April 1979, several ministers from the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, Congress (O) and Bharatiya Lok Dal resigned from the cabinet. The Janata Party itself was split. Jagjivan Ram’s Congress for Democracy (CFD) also decided to quit the Thakur-led Janata Party.

On 19 April 1979, Thakur had to face a floor test, which he lost by 135 votes against 105. His government fell, and Thakur could never become chief minister again.

A lonely man

During the 1952 election campaign, Thakur saw a group of women pasting goitha (dung cake) by the road. He got off his cycle and asked the women to vote for him.

The women lashed out. “Ihe gobar se tora sabke muh rang debau. Hum apna vote Kapoori ke debay (Go away or else I will plaster your face with dung cake. We will vote for Karpoori),” one of them said.

Three decades later, the man with a mass appeal who transformed north Indian politics and brought socialism from esoteric books to the dusty streets of the countryside was left without any significant base.

How did this happen? In the 1980s, Karpoori had famously said that dealing with Yadav leaders was like “riding a tiger”. The statement carries the key to understanding Thakur’s irreversible political decline.

As argued by senior journalist Jagpal Singh in a paper published in the Economic and Political Weekly, although the upper backward castes—the Yadavs, Kurmis and Koeris—had emerged as a significant social and political force in Bihar by the 1960s, they lacked a leader from within their own ranks who could represent them.

Until then, they accepted Thakur’s leadership. By the 1980s, Singh notes, this had changed for two main reasons: first, the reservation policy had already become a reality; and second, a new generation of political leaders from the upper backward castes—many of them mentored by Thakur—had come into their own. Among them were two of his most formidable protégés, Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar.

“Within a short period after the fall of the Karpoori Thakur government in 1979, this new generation realised the numerical significance of their castes and challenged the leadership of Karpoori Thakur, who was handicapped due to the minority status of his caste,” Singh writes.

An anecdote from journalist Sankarshan Thakur’s book, The Brothers Bihari, captures Thakur’s loneliness towards the end of his career while he was still the leader of opposition.

He was ill and convalescing at home. But one day, he had to go to the Assembly. Despite having been the chief minister of the state, Thakur Karpoori did not own a vehicle. He sent word through someone to Lalu, who drove a Willys jeep those days, to ferry him.

Lalu’s reply shocked the messenger. “I don’t have fuel in my jeep at the moment. Why don’t you ask Karpoori ji to buy himself a car? He is a big enough leader.”

As argued by Singh, in 1983, “In collusion with the speaker of the assembly, Shiv Chandra Jha, a senior Congress MLA, who ‘despised Karpoori Thakur,’ the Yadav MLAs, who formed half the strength of the Lok Dal MLAs, challenged the leadership of Karpoori Thakur in the Lok Dal. Soon, he was replaced by Anup Yadav, who then became the leader of the Opposition in the legislative assembly.”

Soon, Anup was replaced by Lalu Yadav.

A desolate Karpoori Thakur lamented, “I would not have faced such humiliation if I were born a Yadav.”

Three years later, Thakur died.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Karpoori Thakur, the other Bihar CM who banned alcohol