Elections seem fascinating in some measure because they reflect the shifts in people’s thinking and aspirations as well as their expectations of the leaders. On November 14, we may know a little more about “Badalta Bihar” when the outcome of the two-phase Bihar Assembly elections will be known.

As the Opposition Mahagathbandhan appeared to be losing momentum following differences in the alliance over seat-sharing, Rahul Gandhi stepped in and reached out to Lalu Yadav. Rahul rushed old Congress hand and ex-Rajasthan chief minister Ashok Gehlot to Patna to salvage a situation which was getting out of hand.

This led to the Mahagathbandhan declaring RJD leader Tejashwi Yadav as its CM face. It was a move that could have been taken weeks ago, but for prevarication and brinkmanship of the Congress.

By naming its CM candidate, the Mahagathbandhan however regained momentum, putting the ruling NDA on the defensive for not having done the same.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah left the CM question open when he recently said that the NDA MLAs will choose their leader after the elections, even as the NDA is contesting the polls under the leadership of the incumbent CM Nitish Kumar.

The Mahagathbandhan’s decision to project Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP) leader Mukesh Sahni as its Deputy CM candidate was also taken under pressure at the last minute, but it may give a fillip to its prospects. Sahni’s elevation may create a resonance among his Mallah group, a sub-caste of the Nishad community, which comes under the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) and accounts for 9% of the state’s population.

Empowering the EBCs, which make up 36% of Bihar’s population, is in line with Rahul’s push and could be the “plus” factor that the RJD is seeking to add to its M-Y (Muslim-Yadav) vote base, which could make a difference between victory and defeat. The 2020 Bihar polls was a close contest, with the NDA edging out the Mahagathbandhan by just .03% vote difference.

Clearly, the BJP has thus decided not to rock the boat and head into the elections under Nitish’s leadership. The BJP high command also decided to give a crucial role to Chirag Paswan, allocating 29 seats to his LJP (Ram Vilas). He is being projected as a young Dalit icon, and not just a leader of his own group, Paswans, whose share in population is 5%.

Another NDA ally, HAM (Secular) leader Jitan Ram Manjhi, who belongs to the Musahar community — among the most marginalised Dalit groups, with 3% share in population — was given only 6 seats. The BJP hopes to win back those Dalits who had switched to the INDIA bloc in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

What has also become evident is that the Bihar fray has thrown up a crop of young leaders — be it Tejashwi, Chirag, Sahni or Prashant Kishor a.k.a. PK.

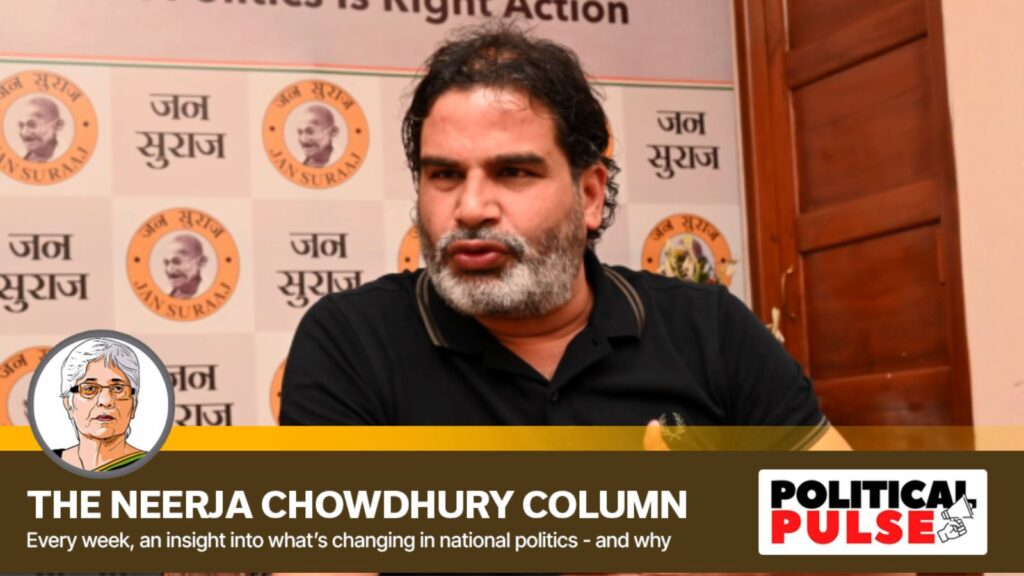

In the countdown to the Bihar elections, the “PK factor” features in every conversation about it. The poll strategist-turned-politician Kishor’s Jan Suraaj has made headlines, caught eyeballs, and got the attention of youths. Tired of old faces and politics, a section of Bihar people has been drawn by his pitch to move beyond caste politics towards ensuring a better future for their children.

PK could be the “X factor” in the polls, having said himself that his party would get either 150 seats of the state’s 243 or below 10. He seemed to be going strong till he decided not to contest the election himself and just focus on campaigning for his party nominees across the state. Had he contested against Tejashwi from Raghopur as he hinted earlier, it might have electrified the polls and helped the Jan Suraaj in several seats.

PK had played a key role in Narendra Modi’s Prime Ministerial campaign in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls. He was then able to use social media and technology to build up Modi’s image and amplify his message, whether it was 3D holograms at rallies or chai pe charcha, tapping both data and digital media for results.

He later did the same for other leaders — including Nitish in Bihar, who even inducted him in the JD(U) as his No. 2 till they fell out; Captain Amarinder Singh (then with the Congress) in Punjab; TMC supremo Mamata Bannerji in West Bengal; and DMK chief M K Stalin in Tamil Nadu. Steering clear of the ideology of parties for which he worked, he only focused on helping them clinch the polls.

And in 2022, PK decided to be a political player himself, undertaking padayatras across Bihar for two years before launching his own party on October 2, 2024 .

There was a time when politicians used musclemen to come to power. Later, several musclemen decided that they could become politicians themselves. Similarly, some businessmen who used to fund politicians also chose to enter the political arena in a bid to influence policy directly. Why could then a poll strategist not become a politician himself – this, in PK’s case, proved to be a natural corollary.

In one of his interviews, PK underlined that he was different from AK (Arvind Kejriwal). Unlike Kejriwal who emerged from the Anna Hazare-led movement against corruption, PK has not risen from any andolan.

In recent times there are only a few examples of political parties being born out of agitations. In 1985, the Asom Gana Parishad was launched as a party in the wake of the All Assam Students Union (AASU)’s movement against illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, which quickly went on to defeat the then dominant Congress in the state.

The TDP was founded by film actor N T Rama Rao, father-in-law of the current Andhra Pradesh CM Chandrababu Naidu, on the plank of Telugu pride. It ousted the ruling Congress in the undivided Andhra Pradesh in the 1983 polls within months of its formation.

Kishor may not be a product of a movement, but he is born out of a social media and communication revolution impacting our lives. The protests buoyed by social media have toppled governments in Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka in recent years.

Many believe that politics has been de-ideologised today, getting linked only to power that stems from winning elections, which in turn rides on skilful management of poll machinery.

Kishor was among those few who first understood this churn in the country. And, even as a leader now, he has built a party in a remarkably short time, so much so that he has now fielded candidates in 243 constituencies (he has accused the BJP of forcing three of the Jan Suraaj nominees to withdraw). But curiously, just as he was emerging as one of the central figures during the campaign, he pulled back by deciding not to take the plunge himself.

It is a moot question whether PK would be a king or kingmaker — or just a courtier who would make his presence felt in the Pataliputra durbar.

(Neerja Chowdhury, Contributing Editor, The Indian Express, has covered the last 11 Lok Sabha elections. She is the author of ‘How Prime Ministers Decide’.)