New archaeological research is turning a long-accepted idea about human evolution on its head—challenging the belief that meat was the cornerstone of early human diets and that plant foods only rose to prominence with the arrival of agriculture.

In a comprehensive study published in the Journal of Archaeological Research, scientists present new evidence showing that early humans across multiple continents were gathering, cooking, and grinding wild plants tens of thousands of years before farming began. The data reveal a far more nutritionally diverse prehistoric diet than previously understood, one that included a wide array of seeds, nuts, and starchy roots.

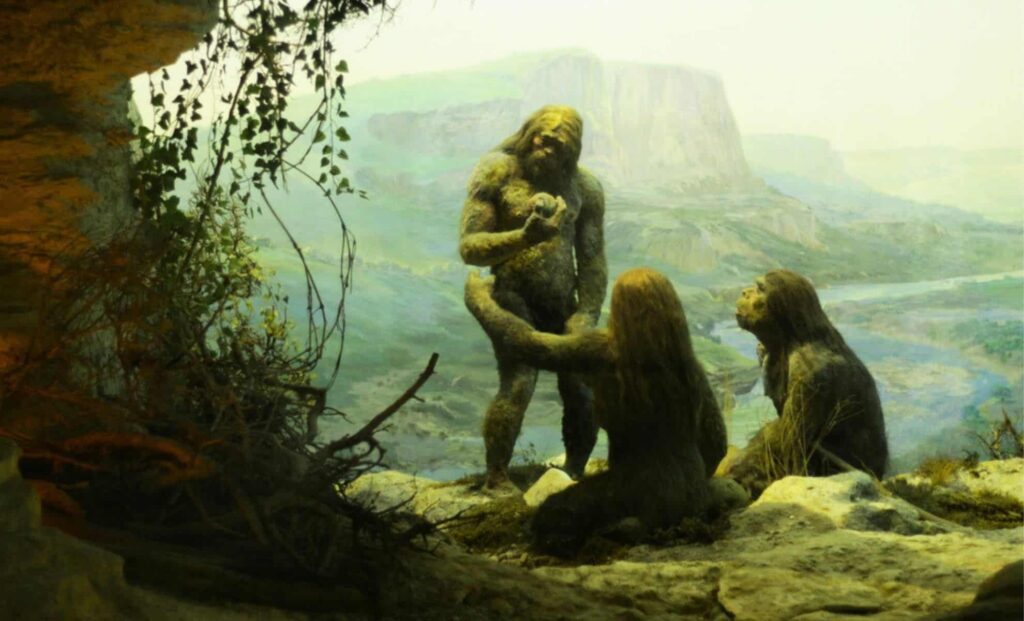

This new perspective disrupts the conventional narrative of human evolution, shaped largely around hunting and animal protein. Rather than viewing plant use as a secondary adaptation or late innovation, the study positions it as a central feature of human dietary flexibility, predating agriculture by tens of millennia.

Grinding Stones and Root Ovens: The Evidence Beneath Our Feet

The research, conducted by teams from the Australian National University and the University of Toronto Mississauga, draws on archaeological data from prehistoric sites spanning Africa, the Levant, Southeast Asia, and Australia. These sites have yielded grinding stones, charred plant remains, and cooking tools—direct evidence of prehistoric plant food preparation dating back at least 35,000 years, and possibly much earlier.

At Ohalo II, a lakeside site in Israel dated to 23,000 years ago, archaeologists recovered grinding tools embedded with starch granules, along with well-preserved remains of wild wheat, barley, and legumes. On the other side of the world, in Madjedbebe, Northern Australia, residues found on stone tools suggest the processing of yams, seeds, and other starchy wild plants more than 65,000 years ago—the oldest known human site on the continent.

These findings—now compiled and analyzed in one of the most extensive global reviews to date—undermine the long-standing belief that early humans relied primarily on hunting large game. Instead, the evidence shows a deep, widespread tradition of plant-based subsistence strategies well before domestication began.

Why Humans Couldn’t Live on Meat Alone

There’s a biological ceiling to how much lean meat humans can digest. Without adequate fat or carbohydrates, high-protein diets can lead to a condition sometimes called rabbit starvation, characterized by nausea, weakness, and eventual metabolic failure. This means early humans needed more than just protein—they needed a reliable source of complex carbohydrates and plant-based fats.

Plant foods—especially those that required processing—offered a dense, portable, and renewable source of energy. Roots, nuts, and seeds, once cooked or ground, could provide vital calories for mobile groups crossing harsh environments like deserts, highlands, and savannas.

The study authors also emphasize the technological innovations that supported this dietary flexibility. Tools such as grinding stones, pounding implements, and earth ovens allowed early humans to unlock nutrients from otherwise indigestible or bitter plants.

Rather than reacting to food scarcity, these groups appear to have had extensive knowledge of local flora, as well as the techniques needed to process it. The scale and diversity of these behaviors suggest a long-term adaptation rather than an opportunistic survival tactic.

Rethinking the “Broad Spectrum Revolution”

For years, archaeologists described the late pre-agricultural period as a “Broad Spectrum Revolution”—a time when humans expanded their diets to include smaller game and plant foods, leading eventually to domestication. But this new research challenges that framing.

Instead of a sudden dietary expansion, the study proposes that humans were always broad-spectrum foragers—a strategy that likely defined our species from its earliest phases. To reflect this, the authors introduce a new term: the “Broad Spectrum Species.” In this framework, diverse plant consumption is not a precursor to farming, but a long-standing evolutionary advantage.

This adaptability may explain why Homo sapiens, unlike other hominins, successfully migrated into such a wide range of ecosystems. The ability to harness both animal protein and wild carbohydrates allowed for survival in regions where one or the other alone would not have sufficed.

Today, roughly 80% of the global human diet consists of plant-based foods. This is often viewed as a byproduct of modern agriculture, but the research suggests otherwise. Our dependence on plants runs deeper—it’s rooted in tens of thousands of years of innovation, selection, and trial-and-error with wild resources.