For more than 260 years, scientists have consider giraffes a single species. Giraffa camelopardalis, as it was long known, existed across thousands of miles of African grasslands and woodlands.

But scientists now see giraffes differently. One species is officially four, the International Union for Conservation of Nature announced Thursday. Conservation biologists will now evaluate the status of each; preliminary data suggest three of the species are threatened with extinction.

“A giraffe is not a giraffe, so to speak,” said Michael Brown, an author of the assessment. “Now we have four different species, each with their own narrative. This has some dramatic implications for how we view giraffe conservation across Africa.”

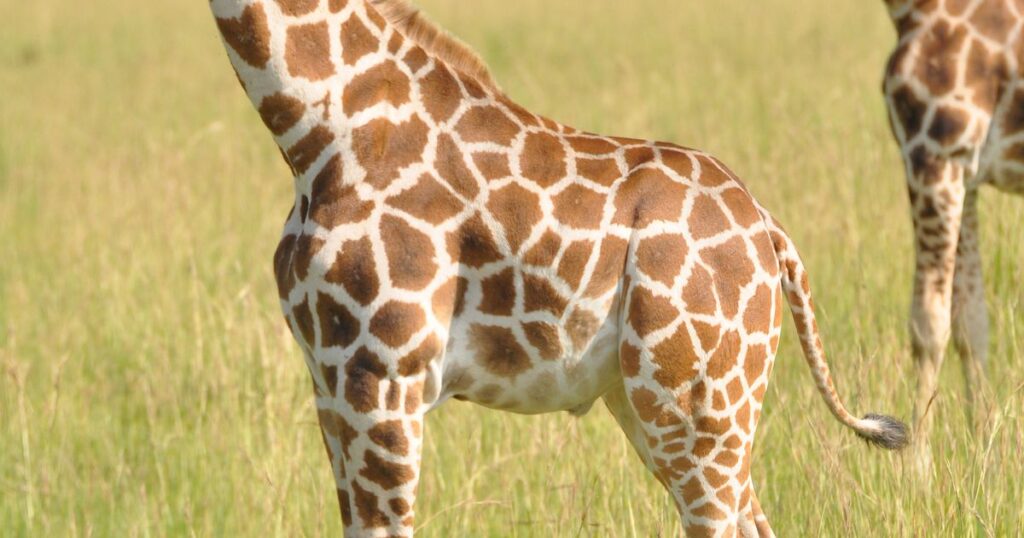

It’s easy to tell giraffes apart from other mammals, thanks to their magnificently long necks. But other, subtle differences set giraffes apart from one another. By the 1800s, for instance, European zoologists who examined giraffe hides that were shipped to museums were noting distinctive patterns and colors among them.

Giraffes in different regions appeared to have distinctive coats, leading some researchers to argue that the species contained eight or nine subspecies — populations that could be distinguished from one another but could still interbreed.

In the 20th century, giraffes suffered a worrisome decline. Rinderpest, a virus that infected cattle in Africa, wiped out many giraffe populations. Fences and roads chopped up their habitat, and poachers killed many of the animals. From 1985 to 2015, the giraffe population declined about 40%.

That drop led the IUCN to declare the species vulnerable in 2016. But that assessment assumed that all giraffes belong to a single species. And new evidence has raised questions about that assumption.

A 2024 study of DNA, for example, revealed that living giraffes belong to four main branches that do not interbreed much since diverging from a common ancestor about 280,000 years ago.

Another 2024 study, of 515 giraffe skulls, revealed anatomical differences between the four groups. Researchers found that the hornlike growths, or ossicones, on giraffes’ heads were significantly different between the groups. Giraffes at the northern end of the animals’ range have a high ossicone jutting up above their forehead, for instance. On giraffes in southern Africa, it forms a low bump.

Reviewing these and other studies, Brown and other giraffe experts agreed the animals belonged to four species, not one.

The species with the biggest population is the southern giraffe, or Giraffa giraffa. It lives in South Africa and surrounding countries and, according to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation’s 2025 annual report, consists of 68,837 animals.

The other three species have much smaller ranges and populations. The Masai giraffe, Giraffa tippelskirchi, lives in eastern Africa. The reticulated giraffe, Giraffa reticulata, has a range extending farther north, in Kenya and southern Ethiopia. And the forth species, the northern giraffe, retains the original name for all giraffes, Giraffa camelopardalis. It survives in scattered pockets from South Sudan to Niger.

Rasmus Heller, a population geneticist at the University of Copenhagen who carried out the 2024 study on giraffe DNA, cautioned that drawing sharp lines between evolving populations can be tricky. “Nature doesn’t fit nicely into species,” said Heller, who was not involved in the new assessment.

He noted that the four proposed species have mixed their genes together from time to time, as giraffes from different populations encountered each other and mated. In fact, the reticulated giraffes are hybrids; their ancestry is about evenly split between northern giraffes and southern giraffes.

“Giraffes are a hard nut to crack,” he said. “You could reach the conclusion that there are different species, or you might not.”

Fred Bercovitch, a conservation scientist at the Anne Innis Dagg Foundation who was not involved in the assessment, said the controversy over giraffes may stem from their vast range. “The more widespread a species is, the more likely you are to have disagreements among scientists about what to call these groups,” he said.

For his part, Bercovitch thinks the IUCN team did not go far enough. The data leads him to view almost all of the subspecies as distinct species; instead of four species, he would recognize eight.

Brown, the conservation science coordinator at the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, said the IUCN would organize teams of scientists to assess the four newly recognized species later this year. The small populations of the northern, reticulated and Masai giraffes could lead to their being classified as threatened species.

The northern giraffe, with only 7,037 animals, faces particularly big challenges to its survival. Its meager population is scattered in isolated pockets, many of which are in countries facing poverty and war.

But even the most threatened giraffe species are not beyond help. In Uganda, conservation biologists have moved dozens of northern giraffes from Murchison Falls National Park to other parts of the country.

“When we started working in Uganda, there were two populations,” said Stephanie Fennessy, the executive director of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation. “Now there’s five, and they’re all growing.” She added, “When giraffes have space and when they’re safe, they breed quite well. So there are really positive conservation stories out there.”