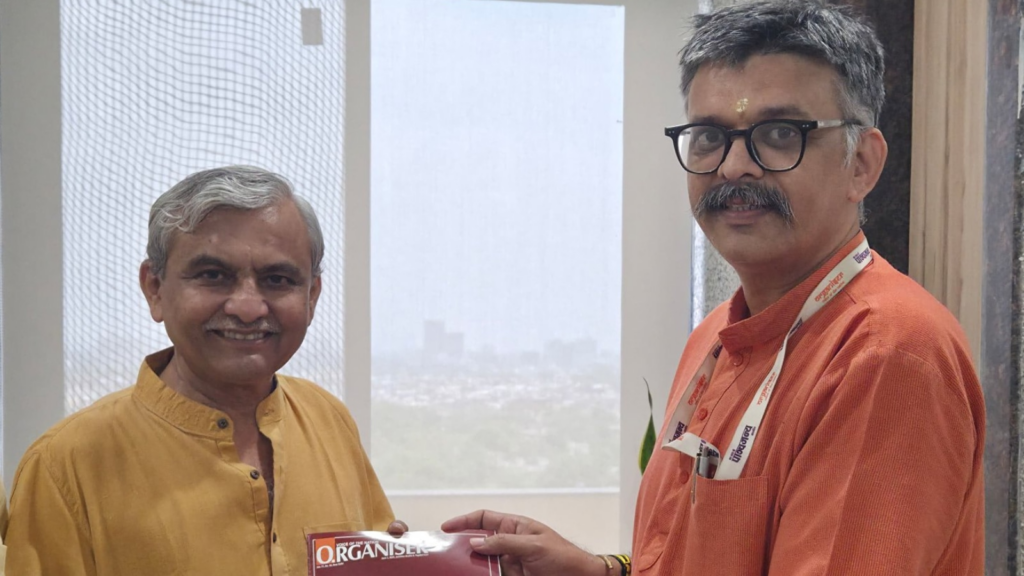

With RSS-affiliated Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) set to mark 70 years of its founding on July 23, its president Hiranmay Pandya discusses in an interview the organisation’s journey from modest beginnings to becoming the country’s largest labour organisation.

Pandya reflects on the BMS’s past, its ideological independence, vision for the future in a rapidly transforming economy, and its selective endorsement of the new labour codes, among other issues. Excerpts:

When Dattopant Thengadi founded the BMS in 1955, there was no fund, office, or cadre. Today, the BMS has grown into the largest labour organisation in the country with over 7,000 trade unions, 41 federations, and more than 2.5 crore members. We are active in 27 states, with offices at the district and the panchayat level, especially in Kerala. For the past 35 years, we have consistently emerged as the number one trade union in the country.

The BMS is taking up leadership roles internationally. It is actively engaged with the International Labour Organization (ILO) and recently chaired the Labour-20 (L-20) group …

We first raised the demand for a bonus in 1965, which was later recognised by the National Labour Commission. This has been possible due to the sacrifice, dedication, and tireless efforts of our karyakartas (cadre). Yet, we have not become complacent. There is much to be done. We are seeking the guidance of RSS sarsangchalak (chief Mohan Bhagwat).

Has the BMS managed to have a greater impact than other RSS-affiliated associate organisations? If so, why?

Credit for this must go to Thengadi. He was a sharp thinker, an economist, and an organiser. He travelled across the country for 12 years and this had a lasting impact on the labour movement. The contribution of each worker has been vital to this success as all workers followed organisational discipline. Our focus must solely be on labour welfare and for that, we need to be apolitical.

The BMS opposed the labour reforms that the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government initiated and even joined forces with the Left. What allowed that ideological leap? Does that spirit exist today?

We do have ideological differences with the Left, but Thengadi spoke of responsive cooperation. The idea is to work for labour welfare. We will stand by those who do good work and against those who do not work for the sector. Ideology is immaterial.

We also opposed the World Trade Organization (WTO), but no one heard us. Today, everyone is acknowledging the problems with it. We have given a slogan for the WTO: “modo, todo, ya chhodo (bend it, break it or leave it)”.

Though the BMS protested against the privatisation of public sector undertakings (PSUs) in 2020, it has continued. What is your stand now?

We believe we were successful (in influencing the government). At the time, the idea was to privatise everything. The government wanted to even privatise the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC). Our protests forced the government to adopt a more calibrated approach. The Covid pandemic showed us that it is the public sector, such as the railways, which stands by society in times of crisis. It is the public sector that stands with the country during war.

Plans were afoot to privatise the railways, but that stopped at the IRCTC. There are questions on the efficiency of PSUs, but those are not labour-related. There are many other factors. Even the management is responsible.

The BMS stayed away from recent protests against the Narendra Modi government’s labour codes. Do you support the codes in the current form? If not, what are your objections?

I would like to make it clear that the BMS always fights for labour rights, irrespective of the government in power. The opposition to the four new labour codes by some unions is political. The BMS has welcomed two new labour codes: the Code on Wages, 2019, and the Code on Social Security, 2020.

For the first time, the Code on Wages empowers the Centre to fix a national floor wage while allowing state governments to set minimum wages at or above that level. Under this code, any worker who puts in eight hours of work is legally entitled to minimum wages.

Similarly, the Code on Social Security, 2020, introduces social security provisions for gig and platform workers for the first time in India. Why should anyone oppose this?

However, the BMS has recommended that the Industrial Relations Code, 2020, and the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020, be amended after in-depth consultations with all stakeholders. In recent months, the government has held discussions with various trade unions and employers, but the BMS believes that these interactions have been inadequate. The government must take this issue more seriously.

Is it harder today to publicly oppose government policies as compared to the Vajpayee era? Do you face pressure from the BJP or RSS?

Regardless of which party is in power, our approach has always been one of responsive cooperation, which entails dialogue first and struggle only when necessary. Be it the Congress or the Vajpayee government, our stance has remained the same. For us, a strike is always the last resort. National interest comes first.

During Operation Sindoor, we did not raise any demands. Once the situation stabilised, we resumed placing our demands before the government. It is also true that many ministers listen to us while others remain indifferent or unresponsive to our concerns. But we press on.

As India’s economy shifts towards gig work and informal labour, how is the BMS adapting? Have you managed to organise workers on platforms such as Swiggy or Ola?

Technology cannot be stopped. Recently, a joint delegation from our organisation visited Japan to study how different countries are adapting. Even in the United States, significant challenges have emerged. The goal must be to embrace technology while also ensuring employability.

We need to find solutions for gig workers. There are also professionals, like some class of lawyers and independent journalists, who currently have no access to social security. We have to work to secure rights and protection for all of them.

The economy is growing, the corporate world is making unprecedented profits, but worker incomes have stagnated. How do you see this situation?

India’s economy is growing, but it must remain human-centric or else it will not be sustainable. It is true to some extent that incomes are not rising proportionately. Though PSU employees have seen a good wage growth, even temple priests have received better pay.

Along with minimum wages, workers must be ensured a living wage. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs has also emphasised the need for responsible business conduct. This is the direction we must move in, and ensuring dignified work and dignified wages must be our approach.

Even the definition of the middle class is changing today. At the state level, we pushed for higher wages for Anganwadi workers and managed to get their honorarium increased from Rs 500 to Rs 10,000. But even Rs 10,000 is too little. It must be raised further.

What should workers expect from the BMS in the next decade: more protests, deeper grassroots presence, or a more collaborative stance with the government?

Just as the BMS has risen over the years, we must continue to grow further. New technologies will keep emerging, but we must carefully evaluate which ones to adopt and which to avoid. Progress must be thoughtful and balanced.