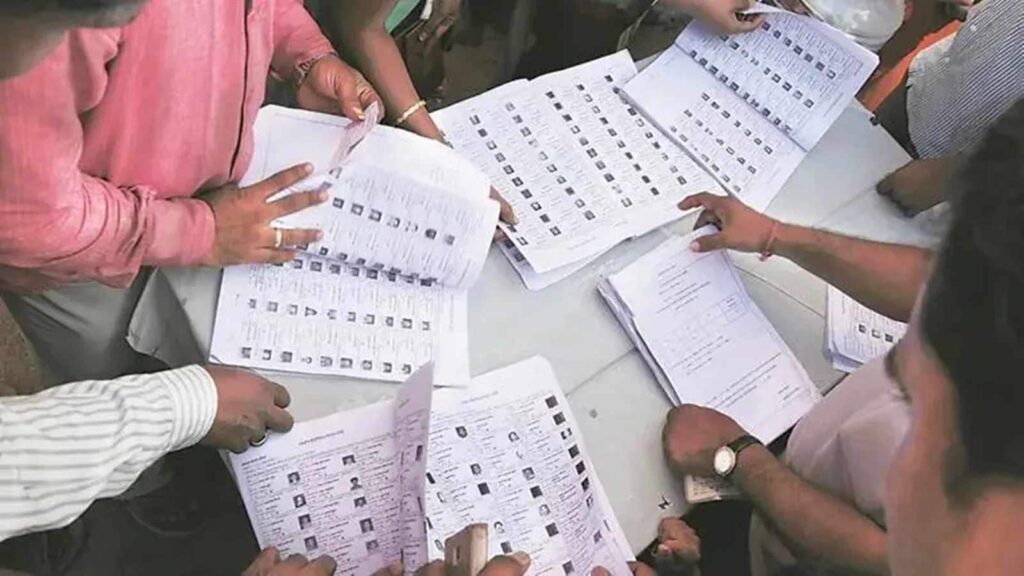

Citing the findings of the Congress’s internal investigation, Rahul Gandhi, Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha, had alleged last week that over one lakh votes were “stolen” in Karnataka’s Mahadevapura Assembly segment — part of the Bangalore Central Lok Sabha seat — during the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. Of these, he said, nearly half involved irregularities in electors’ addresses.

While the Election Commission (EC) is yet to respond to the charge, the claim spotlights a long-standing challenge for the poll body — the absence of standardised addresses for many voters, and the continued practice of assigning “notional” house numbers.

Gandhi said the Congress analysed the Mahadevapura electoral rolls over six months and found that of 1,00,250 alleged bogus voters, 40,009 had “fake and invalid addresses” and 10,452 were “bulk voters” registered at common addresses. Examples included entries with “0” in the address field, non-existent locations and addresses that could not be verified.

For much of India’s electoral history, the electoral rolls were simple lists with only the elector’s name, age, a relative’s (father, mother or husband) name, constituency and serial number. While the “house number” column was there, it was often left blank.

Some pages of the rolls from 1980, 1983 and 1988 examined by The Indian Express list only the serial number, name, gender and age in most cases, with house numbers given for some electors. However, some of these house numbers were notional, they were known as “temporary house number”, an official said.

The EC began computerising the rolls in 1998 and introduced photo electoral rolls in 2005, according to its 2023 Manual on Electoral Rolls. It was during this shift to digital records that the practice of assigning “notional” addresses became standard across the board, ensuring that electors without a permanent or well-defined address — or those who left the field blank — were not excluded from the database.

The problem of inconsistent or informal addresses goes beyond the drafting or revision of electoral rolls. The Centre has repeatedly acknowledged it as a long-standing challenge – most recently in May, when the Department of Posts, in a policy document, proposed creating a digital public infrastructure to standardise addresses. “Despite the centrality of address information in everyday life, frictions exist in how such data is managed, shared and used across India,” it noted, citing linguistic diversity, inconsistent formats and fragmented address data.

Current and former Election Commission (EC) officials told The Indian Express that over time, when electors either lacked a proper address or left the field blank, they were assigned “notional” addresses to ensure their inclusion in the rolls. EC instructions dating back to at least 2011 – and reiterated as recently as June 24 for the ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar — direct that such numbers be allotted and clearly marked as “notional” in the roll. Identical wording appeared in instructions to Chief Electoral Officers of poll-bound states, including Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Rajasthan and Telangana, in May 2023.

Officials said the practice exists nationwide, but tends to draw greater attention in urban constituencies with high migrant populations and unplanned settlements. It stems from the Commission’s stated philosophy of inclusion, not exclusion, from the electoral roll. For example, in the case of homeless persons, EC guidelines instruct Booth Level Officers (BLOs) to verify the address given in Form 6 at night — checking on more than one occasion — to confirm that the person actually sleeps there. No documentary proof of residence is required if this is established.

A 2011 EC training module for BLOs stated that where a municipality has assigned house numbers, those should be used, as they also appear on Electors Photo Identity Cards (EPICs) that double as address proof for other government schemes. Where no official number exists, or the sequence is irregular, BLOs are to assign notional numbers starting from 1 in each section. These numbers, the manual noted, are “computer generated” and “not necessarily in consonance with the number allowed by the municipality”.

In illegal colonies, municipalities sometimes allot “0” as a house number to avoid conferring legal status, an official said. It is unclear whether this was the case in the addresses Gandhi cited.

A former Chief Election Commissioner, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the quality of electoral rolls has improved over the years and a notional address was not an irregularity. Similar objections have surfaced earlier — during the 2023 Telangana Assembly elections, for instance, the BJP flagged voters listed with “0” as their house number. In the most recent draft roll published in Bihar on August 1, the use of notional numbers has continued.