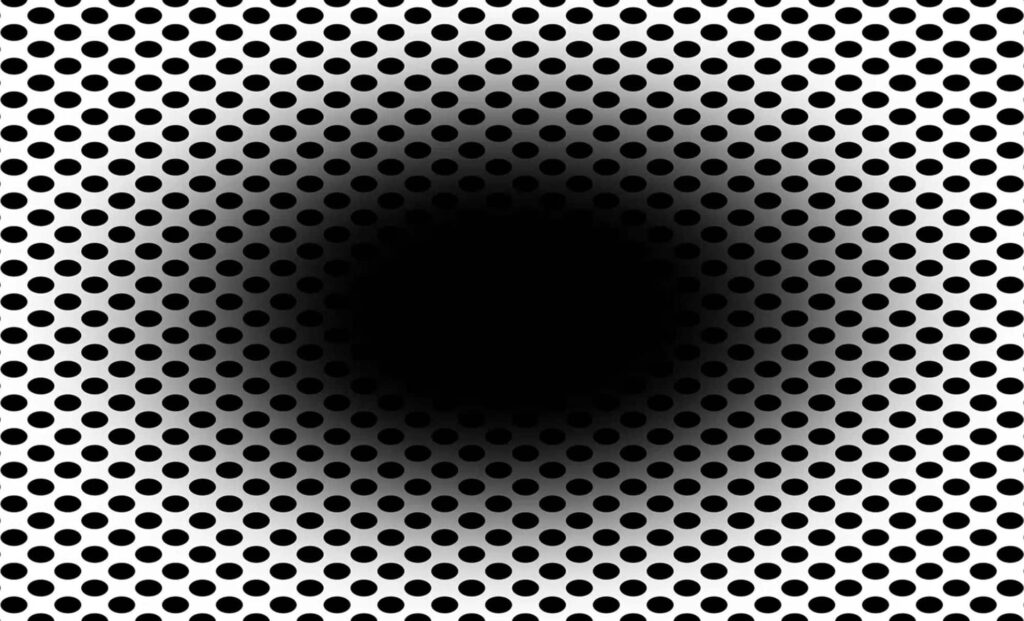

A static image that seems to pulsate like a growing tunnel has been puzzling neuroscientists and delighting the internet in equal measure. At first glance, it looks like nothing more than a black blur in the centre of a white background filled with scattered dots. But for most people, something remarkable happens: the dark shape appears to expand. Some even feel a subtle sense of being drawn inward.

What makes this illusion more than just a viral curiosity is what happens behind the eyes. Researchers at the University of Oslo found that when people stare at the centre of this image, their pupils dilate—as if they were actually moving into a darker environment.

The study, published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, not only confirmed this strange visual trick but uncovered a startling fact: roughly 20% of people feel nothing at all. Their eyes stay still. Their pupils don’t change. The illusion passes them by entirely. And no one yet knows why.

A Test That Goes Beyond What You See

Unlike many optical illusions that rely purely on misperception, this one activates deeper systems. The team, led by Dr Bruno Laeng, used infrared eye-tracking to measure pupil changes in 50 participants as they stared at various images designed to trigger the effect. The results were surprisingly clear.

When shown a black hole against a white background, most pupils dilated noticeably—a reflex normally reserved for entering low-light conditions. This reaction wasn’t voluntary, nor was it something participants were necessarily aware of. Yet their bodies behaved as if they were stepping into darkness. In contrast, when the central region was coloured (green, red, cyan or white), participants’ pupils tended to constrict, as if preparing for increased brightness.

The illusion’s power wasn’t just anecdotal. Participants also rated how strongly they experienced the sensation of the hole expanding. Those who saw it more vividly had a stronger physiological response, indicating a close link between subjective perception and bodily reaction.

“These findings show that the pupil responds not only to actual light, but to what we believe is happening in our environment,” said Laeng. “In some ways, our eyes are reacting to imagined changes in light—an internal simulation.”

One in Five People Are Immune—And No One Knows Why

Not everyone is affected, though. Around 20% of those tested didn’t report any sense of expansion and showed no measurable change in pupil size. They simply saw a black spot. For a study so precise in its measurements, this variability was unexpected.

Interestingly, the difference wasn’t explained by obvious factors like vision problems or lack of attention. The team ruled out eye movement patterns, saccades, or blinking as causes. This raises broader questions about how individuals construct visual reality—and whether some brains are wired to ignore certain illusions entirely.

One theory, dubbed “perceiving the present”, suggests our brains constantly predict what will happen milliseconds into the future to account for neural delays. In this case, seeing the hole expand might be a form of internal compensation, preparing us to move forward into a darkened space—even if we’re standing still.

What Illusions Can Reveal About the Brain

The study joins a growing body of research exploring how optical illusions influence not just perception, but physiology. Prior studies (Laeng & Endestad, 2012; Suzuki et al., 2019) have shown similar effects with bright illusions, where the eyes constrict even in the absence of real light. This highlights the adaptive nature of the visual system, tuned not just to reality but to what it predicts will happen next.

There’s practical relevance, too. The illusion has already sparked interest in its potential to help researchers study neurodivergent perception, or to better understand conditions where visual processing differs from the norm. It also underscores the brain’s dependence on prior experience and environmental expectations to construct what we “see”.

“The brain isn’t just a camera,” Laeng noted. “It’s a storyteller, and sometimes it writes a chapter before the light even changes.”

As online interest in perception experiments continues to grow—fueled by viral tests and social media debates like #TheDress or #YannyLaurel—this illusion offers more than a fleeting curiosity. It’s a window into how the brain builds reality, even when that reality doesn’t exist.

For those interested in trying it themselves, the original stimulus used in the study is publicly available via the Asahi brightness illusion repository, maintained by co-author Akiyoshi Kitaoka, a specialist in perceptual design.