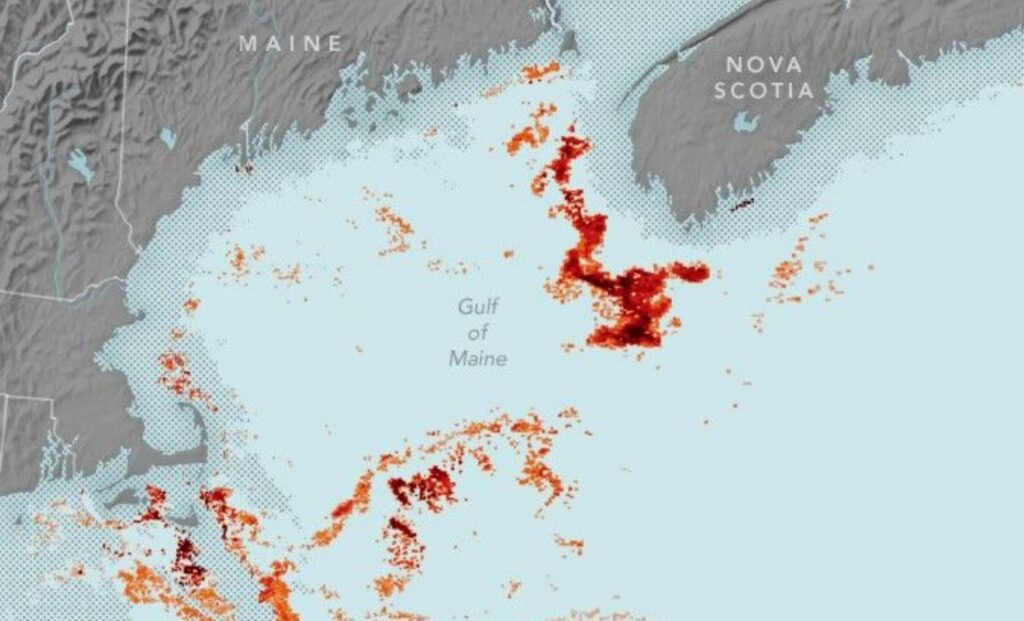

Far off the New England coast, NASA’s Aqua satellite has detected massive clouds of tiny red plankton—Calanus finmarchicus—critical to the survival of the North Atlantic right whale, one of the most endangered species on Earth. This marks the first time these microscopic crustaceans, packed with energy-rich fat, have been tracked from space, offering a new way to protect marine ecosystems from orbit.

With an estimated 370 individuals remaining worldwide, the North Atlantic right whale depends heavily on dense patches of this specific zooplankton to build the energy reserves needed for long migrations. Detecting the presence and concentration of Calanus finmarchicus through remote sensing could help conservationists anticipate whale movements and reduce deadly encounters with ships and fishing gear.

Led by satellite oceanographer Rebekah Shunmugapandi from the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Maine, the research team focused on the Gulf of Maine, where layers of Calanus form a concentrated, high-calorie buffet for whales, fish, and seabirds. Losing these plankton in the region would weaken nearly every predator higher up the food chain. Until now, scientists relied on ships to tow fine-mesh nets through the ocean and manually count the plankton—an expensive, time-consuming process that offered only a small window into vast marine habitats.

Using Satellite Sensors To Identify Underwater Life

The new satellite method uses MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) aboard NASA’s Aqua satellite, which measures how various wavelengths of sunlight bounce back from the ocean’s surface. When Calanus finmarchicus gather near the top layers of water, their bodies—rich in astaxanthin, a red pigment—absorb blue-green light in a way that subtly alters the ocean’s surface color.

According to Earth.com, Shunmugapandi’s team processed MODIS data into enhanced color maps that highlighted abnormal red zones. One such image from the Gulf of Maine showed a dense patch estimated at about 150,000 individuals per cubic meter. To confirm the presence of Calanus, researchers compared each pixel’s coloration to a digital library of simulated ocean colors, both with and without the crustaceans. When the ocean appeared redder than expected in the model without Calanus, the team inferred a high concentration of copepods.

The technique was previously tested in the Norwegian Sea, where similar satellite analysis detected Calanus finmarchicus swarms more than 400 square miles wide—visible directly in the imagery. That earlier work confirmed that large zooplankton swarms can measurably alter ocean color at a regional scale, laying the groundwork for more advanced detection methods.

Confirming Accuracy With Plankton Recorders

To strengthen the reliability of their satellite readings, scientists in the Gulf of Maine paired MODIS imagery with measurements from a Continuous Plankton Recorder, a towed instrument that collects surface samples of plankton. The comparison helped confirm that the unusual red patterns detected from orbit did, in fact, correspond to dense clusters of Calanus finmarchicus.

Until recently, remote sensing mainly focused on phytoplankton, the microscopic plant-like organisms at the base of the food web. Larger zooplankton like Calanus had remained mostly invisible to satellites. According to the researchers, no one had previously known to look for Calanus finmarchicus using this optical method, making this a significant step forward in the use of satellite technology for marine life tracking.

Following The Food Trail To Protect Whales

The movements of North Atlantic right whales are tightly linked to the location of Calanus finmarchicus swarms. The whales feed by skimming these crustaceans at the surface, and when food becomes harder to find, they move beyond traditional feeding grounds—sometimes into shipping lanes and fishing areas where the risk of entanglement and collisions increases.

Ocean-wide maps of Calanus could eventually help scientists forecast where whales are likely to travel in any given season. Better predictions would enable quicker responses, such as voluntary slow-downs, temporary fishing closures, or adjustments to vessel routes, especially when whales are observed in unusual concentrations.

The researchers believe satellite data could soon be integrated with real-time whale sighting reports, helping authorities decide when and where to implement protections. With ship strikes and entanglement already the top human-related threats to right whales, any method of early detection could save lives.

NASA’s Expanding Role In Ocean Conservation

This development reflects a broader shift in how NASA’s space-based tools are being used to address real-world problems in the ocean. According to the scientists, the satellite’s ability to detect Calanus finmarchicus offers a new way to support marine science, local communities, and ecosystem management.

Though the MODIS sensor is aging, its mission will soon be continued by PACE (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem), a new NASA satellite capable of detecting over 280 bands of reflected light. This increase in color sensitivity should allow researchers to distinguish red zooplankton swarms from other features like brown algal blooms or murky coastal waters.