A resident of Nauka Tola in Gopalganj, his name is among 124 voters struck off from the rolls of the local polling station during the Election Commission of India’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR).

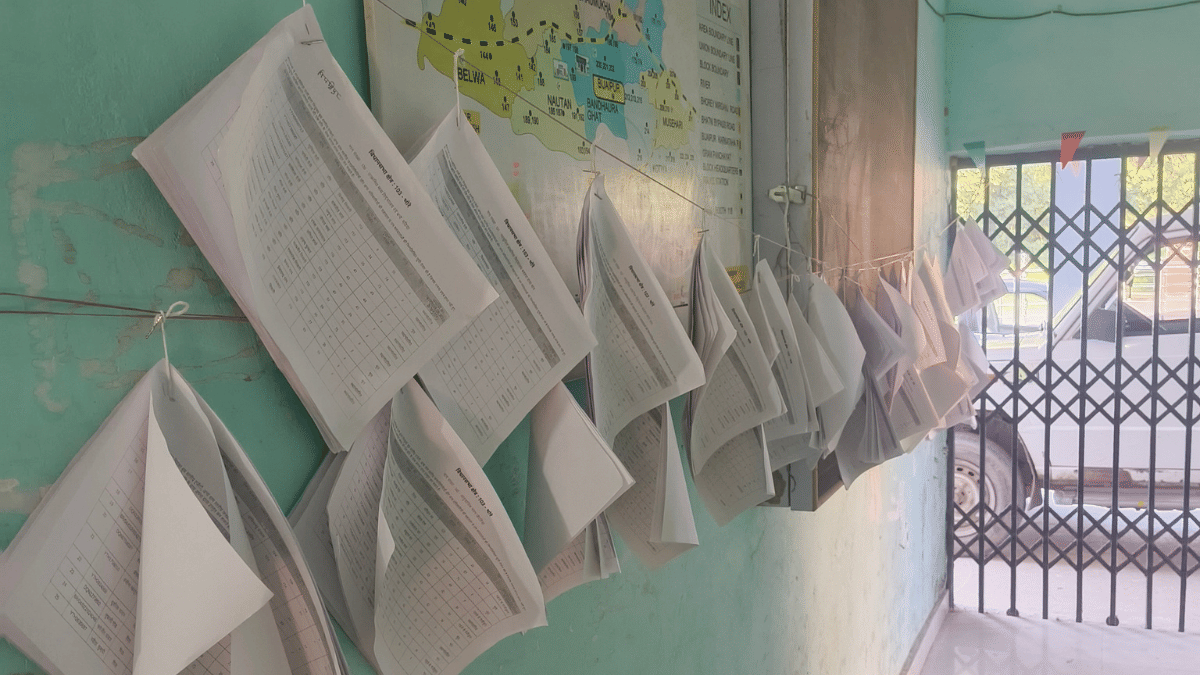

The list of deleted names, along with reasons for their exclusion, was announced on 17 August after the first phase of the sweeping and controversial revision. In the case of Nauka Tola, the reason cited in each case of deletion was death.

However, according to the district administration’s own admission to ThePrint, at least 21 of those listed as deceased are, in fact, alive in Nauka Tola, located 60 kilometres away from the Gopalganj district headquarters.

Even as the massive exercise has triggered a political storm, with the Opposition alleging it’s a ploy to selectively delete anti-NDA votes, the dominant sentiment on the ground is that the deletions have affected voters across political leanings, including those who vote for the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA).

Kushwaha, for instance, is rather vocal about his support for the ruling JDU-BJP alliance. Nauka Tola comes under the Bhore assembly constituency, currently held by the JDU’s Sunil Kumar.

“It’s not just me. My family members, as well as a large section of villagers, including those whose names have been deleted, support the NDA. We want peace and development. “Only a handful of unruly elements in the village support the Opposition,” Kushwaha told ThePrint.

The villagers of Nauka Tola, largely members of the Bhumihar and Rajbhar communities, dismiss the suggestion that the SIR was conducted to selectively remove Opposition-leaning voters.

But does being “officially dead” not bother Kushwaha at all?

“Such things happen,” he said, with a tone of weary acceptance. “My name got shifted to the newly created polling booth. Instead of listing me as shifted, I was tagged as dead. But the BLO, sir, didn’t do it on purpose. He was my teacher in school.”

The BLO, or Booth Level Officer, in question is Jitendra Pandey, a government schoolteacher temporarily deputed to update the voter rolls as part of the SIR exercise being conducted across all 90,712 polling stations in the poll-bound state.

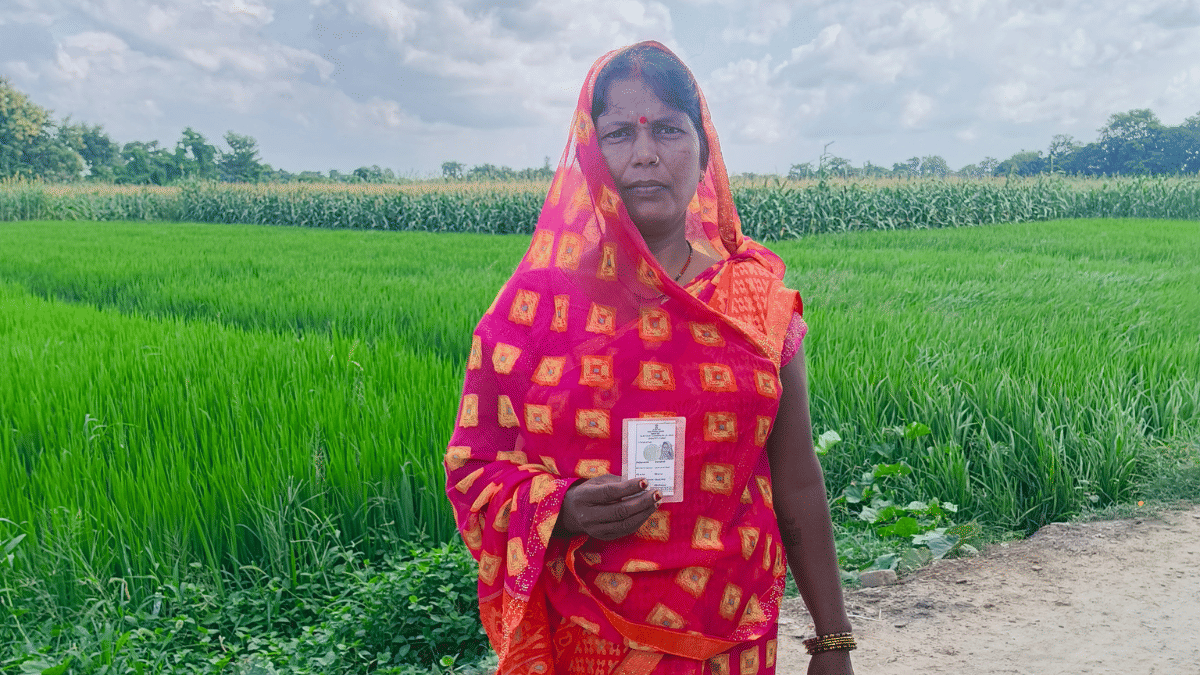

Lali Devi, 39, another resident of Nauka Tola, discovered last week that her name was also among the 124 electors from the village marked as deceased. A supporter of the ruling alliance, she said the BLO has assured her that her name will be reinstated on the voter list.

However, for the Opposition, particularly the CPIML, which has a strong presence in Bhore, these aren’t harmless mistakes.

Guddu Ram, a Dalit landless labourer from nearby Babhanauli village, accused the ECI of deliberately disenfranchising the poor, especially CPIML supporters.

But within his own family, there’s disagreement. Guddu’s grandfather, Dukhi Ram, is on the deletion list. “The BLOs didn’t come door-to-door,” said Shintu Ram, another relative. “They relied on word of mouth. Anyway, our grandfather is bedridden. “Our names are safe,” he said.

Isaravati Devi, 44, of the same village, said she was surprised to find her name missing but is not overly concerned. “The BLO didn’t come to my house during the revision. But he brought a form last week and took my signature. He said it’s being fixed.”

It’s not just Nauka Tola. Across villages in Gopalganj district, which recorded the highest percentage of deletions under the SIR, people appear largely unbothered by the issue.

ECI data shows Gopalganj, which is the native place of RJD supremo Lalu Prasad, registered a 15.01 per cent dip in voters as compared to the numbers that it had on 24 June before the exercise began. It is followed by Purnia, which saw a 12.08 per cent deletion, whereas it was 11.82 per cent in Kishanganj.

“Vote chor, gaddi chhod. Bataiye, ye bhi koi mudda hai?” says Pratyush Kumar Rai, a resident of a village in Gopalganj. “(But) the survey (SIR) should not have been carried out so close to the elections. Had there been more time, it would have been better.”

Late in August, the Voter Adhikar Yatra of Leader of the Opposition in Lok Sabha Rahul Gandhi and RJD leader Tejashwi Yadav also went through parts of Gopalganj, which is a stronghold of the ruling NDA. The JDU has won the Gopalganj Lok Sabha seat three times since 2009, including 2019 and 2024, and the BJP in 2014.

Of the six assembly seats in Gopalganj, two each are held by the BJP, JDU and the RJD.

“Vote chor, gaddi chhod.” “Bataiye, ye bhi koi mudda hai?” said Pratyush Kumar Rai, a resident of Baraipatti village, which falls under Gopalganj’s Niranjana polling centre, which has seen 641 deletions, the highest for any polling station in Bihar.

Of those removed here, 599 were marked as permanently shifted, 39 as deceased, and three as absent.

A Bhumihar by caste, Pratyush, who runs a small poultry business, believes the Opposition, primarily the RJD-Congress-Left alliance, has failed to grasp the public mood by raising an issue that, in his words, has “absolutely no resonance on the ground”.

“The survey (SIR) should not have been carried out so close to the elections. Had there been more time, it would have been better. The names of a few women have been deleted, but they will be reinstated once they produce documents from their parental villages. But it’s not an election issue,” he said, a sentiment echoed by several other villagers gathered around him.

Rahul Gandhi, told a gathering of MPs in Parliament’s Central Hall last month, with apparent cheer, that the Opposition’s campaign on alleged election manipulation had resonated so strongly in poll-bound Bihar that even children as young as four were chanting, “vote chor, vote chor” (vote thief).

‘A wasted opportunity’

But in Gopalganj’s Niranjana village, in the midst of paddy and sugarcane fields, the residents say the Opposition’s Voter Adhikar Yatra (Voter Rights March) could have gained more by spotlighting issues that actually matter on the ground.

“It was a wasted opportunity,” said Dinesh Thakur, a resident of Niranjana. “When the Yatra passed through Gopalganj, even I went to see Rahul and Tejashwi. But their vehicle just breezed past us,” he said.

For Thakur and others in the village, the key issue that should have been raised wasn’t voter roll deletions, but the continuing closure of the Sasamusa sugar mill, once a major source of income for farmers in the region.

“In the last election, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had promised he would reopen the Sasamusa mill. He said he would drink tea with sugar produced right here. But it remains shut. Farmers’ dues are pending. There’s a urea crisis. People lost money in the Sahara and are still repaying loans. Youth are still migrating for work. These are the issues a strong Opposition should talk about, issues that have a bearing on livelihoods,” Thakur said.

A Block Development Officer (BDO) from one of Gopalganj’s 14 blocks, speaking to ThePrint on the condition of anonymity, attributed the high deletion numbers in Niranjana largely to displacement caused by erosion along the Gandak River, a tributary of the Ganga.

“A large number of families relocated after their settlements were washed away. They got new voter IDs at their new locations, and the deletions were made to prevent duplication,” the BDO said.

Other officials and locals point to deeper, longstanding demographic trends unique to Gopalganj. One of them is migration.

“In the last election, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had promised he would reopen the Sasamusa mill. He said he would drink tea with sugar produced right here. But it remains shut. Farmers’ dues are pending,” says a villager in Gopalganj.

“Historically, people from Gopalganj have travelled abroad, to places such as Dubai, Kuwait, and Qatar,” said another BDO. “They work as drivers, plumbers, and painters. These overseas networks have been built over generations. Many men haven’t returned for years. That’s why their names have been listed as permanently shifted,” he said.

One such name to have been deleted is Munna Kumar Ram of Bharpurwa village, said his father, Ramakant Ram, a Dalit farmer. Munna, he said, has migrated abroad for work.

That migration is deeply woven into Gopalganj’s social fabric is also reflected in data. The district has Bihar’s highest sex ratio at 1,021, well above the state average, a figure many attribute to the long-term outmigration of men.

Gopalganj, along with neighbouring Siwan, also receives the highest amount of foreign remittances in the state.

The BDOs also point out that due to Gopalganj’s border with Uttar Pradesh, over the years, many from the neighbouring state bought land, got it registered, and made voter IDs here.

“They were deriving welfare benefits from Uttar Pradesh as well as Bihar. Many such names have been deleted as well, leading to a dip in the overall numbers of electors,” said a BDO, wishing anonymity, claiming he is not authorised to speak to the media on issues related to SIR.

As per official data, a total of 3.10 lakh names were deleted from Gopalganj’s electoral rolls under the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) exercise. Among these, 71,135 were listed as deceased, 1.29 lakh as permanently shifted, 35,258 as holding multiple voter IDs, and 75,070 individuals were marked as untraceable.

Records also show that the district election authorities have received 58,315 claims and objections regarding the deletions, including 39,995 through Form-6, which allows for enrolment of new voters, 4,665 through Form-7 (removal or deletion of dead voters), and 13,647 through Form-8 (correction and shifting of names).

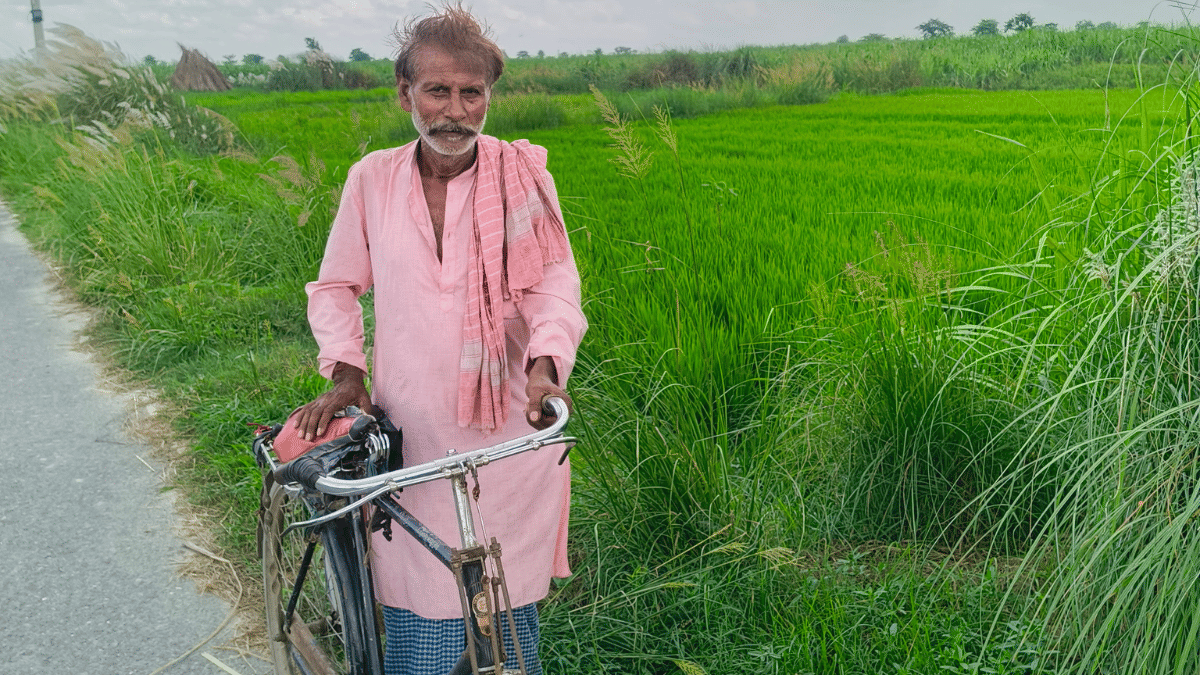

Kashi Ram, 71, a landless labourer in Niranjana, said he had no reason to believe his name would be struck off the voter rolls. After all, it had appeared in the 2003 list, which he said should make him eligible this time as well.

Leading ThePrint to his thatched hut, along a muddy path cutting through paddy fields, he pointed out that even with a valid voter ID, he hasn’t been receiving any welfare benefits.

“The Opposition says we won’t get welfare schemes if our names are deleted from the rolls. But I am not getting them anyway. This is how I have always lived—in abject poverty. There is not even a road leading to the Dalit tola of the village. I haven’t received my old-age pension in nearly six months,” he said.

Then there are those for whom PM Modi’s invocation of national and religious pride remains a powerful and enduring source of appeal.

Take, for instance, Hari Mishra, a farmer found dozing in the afternoon when ThePrint caught up with him on a patch of farmland abutting National Highway 28 that slices through Bihar towns like Muzaffarpur and Gopalganj before entering Uttar Pradesh.

“How is SIR an issue?” he asked dismissively. “It only bothers those who don’t have papers to prove their citizenship,” he said, brushing aside suggestions that the voter roll revision and deletions under the SIR could fuel resentment against the ruling JDU-BJP alliance.

Instead, what stood out for him was Modi’s handling of diplomacy, specifically, his response to the imposition of 50 per cent tariffs on Indian exports to the United States by President Donald Trump. That, Mishra said, had further cemented the Prime Minister’s stature as a global leader.

“He didn’t even take Trump’s calls. Wo call karte reh gaye (Trump kept dialling Modi). Instead, he allied with China and Russia. Didn’t you see?” Mishra asked, his voice tinged with unmistakable pride.

Nearly 150 kilometres away, in the state capital of Patna, Vishnu Sah was tending to his food cart outside the Patna High Court. Just metres away, Rahul Gandhi and Tejashwi Yadav were marking the culmination of their Voter Adhikar Yatra by garlanding a statue of B.R. Ambedkar.

But Sah, a Baniya by caste, seemed unmoved. “Yeh sab jhooth-mooth ke mudde hain,” he said dismissively, adding, “These are pointless issues meant to deceive people.”

When asked what issues mattered to him, Sah pulled out a copy of Prabhat Khabar, a widely read Hindi daily. “Read this part,” he said, pointing to an infographic on one of the inside pages.

The graphic highlighted Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s consistently high global approval ratings, especially in comparison to world leaders like Trump.

“While Trump’s ratings are falling just seven months into his second term,” the infographic read, “PM Modi’s global approval rating remains at 74-75 percent. Trump’s rating is not even half of Modi’s.”

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: Can ECI demand oath from Rahul Gandhi on ‘vote chori’ allegations? Here’s what the law says