The discovery centers on fossils excavated from the Sima de los Huesos site in Atapuerca, Spain, where scientists have found more than 1,600 skeletal remains dating back around 500,000 years. These bones, belonging to a population of ancient hominins, display signs of chronic health conditions that appear to recur cyclically—matching the kind of biological strain experienced by hibernating animals.

This raises the question of whether early hominins, lacking fire, sufficient food storage, or warm clothing, opted instead to spend months inside caves during winter, relying on a form of torpor to endure. While modern humans no longer exhibit this behavior, the idea that hibernation was once part of our evolutionary history could reframe long-held assumptions about human adaptability in prehistoric climates.

Signs of Seasonal Stress Etched in Bone

The study—carried out by paleoanthropologists from Greece and Spain—focused on identifying recurring skeletal pathologies in fossils from the Sima de los Huesos site. According to Popular Mechanics, researchers found a consistent pattern of bone damage indicating chronic kidney disease, likely caused by prolonged periods of malnutrition and lack of sunlight.

Among the conditions observed were “trabecular tunneling,” “osteitis fibrosa,” “rachitic osteoplaques,” and other symptoms associated with vitamin D deficiency and calcium imbalance. These pathologies were found mostly in adolescent remains, pointing to repeated periods of growth interruption. The team interpreted these signs as the result of metabolic stress endured during extended, inactive periods, most likely during winter months.

The scientists concluded that this damage wasn’t constant throughout the year but instead appeared seasonally. That periodicity suggests the population experienced annual cycles of physiological strain, compatible with a poorly adapted attempt at hibernation. As noted in the article, “[t]hese extinct hominins suffered annually from renal rickets, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and renal osteodystrophy… caused by poorly tolerated hibernation in dark cavernous hibernacula.”

Cave Sheltering as a Survival Mechanism

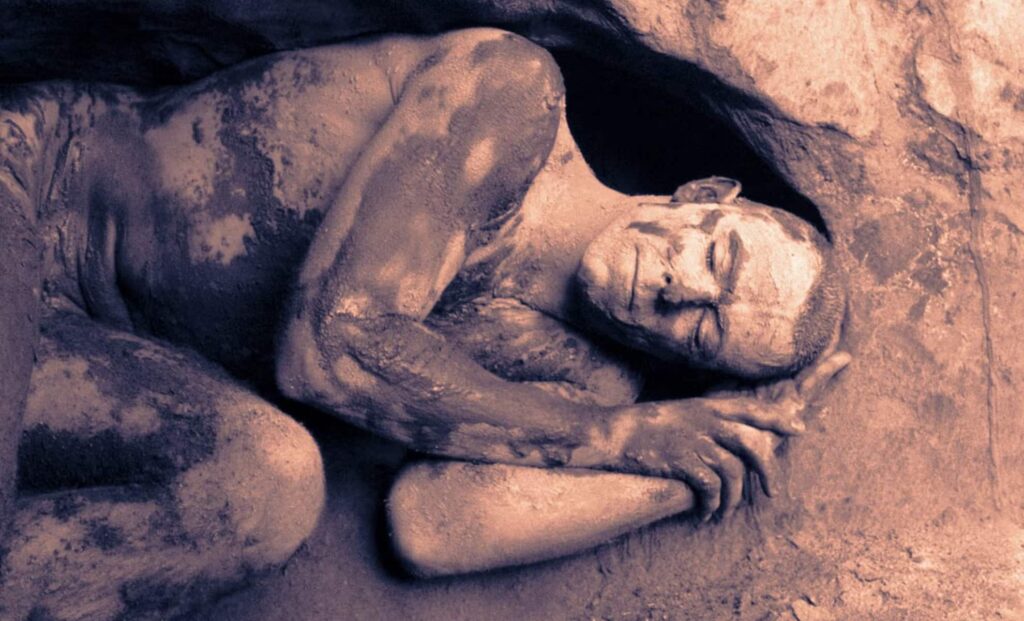

The location of the fossils—deep within the Cueva Mayor cave system—offered more than just protection from predators or weather. The consistent use of caves for shelter may have been linked to a broader behavioral strategy aimed at enduring the coldest parts of the year. Caves provided dark, insulated environments that would have allowed hominins to reduce energy expenditure and avoid external threats while their bodies underwent a slowdown in metabolic functions.

According to the fossil evidence, these early hominins seemed to have relied heavily on their cave habitats not just occasionally, but seasonally. This behavior may have extended beyond shelter to include intentional reduction of activity, akin to a state of torpor or semi-hibernation.

The idea that ancient humans could have entered a form of suspended animation during the winter also aligns with their limited means of coping with cold climates. With no evidence of sophisticated clothing or sustained food storage at that point in prehistory, retreating into caves and slowing biological functions may have been one of the few options available.

The Physiological Cost of Adaptation

While hibernation could have been a temporary solution to environmental stress, the fossil record makes it clear that it came at a steep price. The numerous signs of bone degradation—especially in developing adolescents—suggest that this adaptation was far from optimal. Unlike modern hibernating mammals, which have evolved efficient systems to manage nutrient use and bone density during dormancy, these early hominins appear to have struggled with the biological demands of such behavior.

The researchers emphasized that these skeletal deformities reflected a breakdown in the body’s ability to regulate minerals and maintain healthy bones over extended periods without sufficient nutrition or sunlight exposure. As Popular Mechanics explains, the trade-off for surviving winters in dark, safe enclosures was an increased vulnerability to chronic disease and developmental problems.