BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — The floats thrummed to the Argentines dancing in rainbow bikinis, leather boots and angel wings beneath the blooming jacaranda trees of Buenos Aires, as the drag queens’ sequin skirts sparkled with the warm light of spring.

For Argentines, it was just the city’s annual Gay Pride celebration. But for a Russian gay couple joining this month’s festivities, they were scenes from another planet.

“It’s the most freedom I have ever seen,” said one of them, Marat Murzakhanov, 23, who is from the Russian city of Ufa, near the Ural Mountains. “We want to stay here.”

They are not the only ones.

Argentina has emerged as a surprisingly prominent, if geographically distant, haven for LGBTQ+ Russians escaping President Vladimir Putin’s escalating anti-gay crackdown.

Many waves of exiles since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine three years ago — seeking to avoid conscription or repression — have flowed into neighboring states such as Georgia, Kazakhstan and Armenia. But many LGBTQ+ Russians struggled to stay in those places, facing stigma and a lack of legal protections.

With restrictive visa policies shutting off paths to Europe and the United States, they scoured the world for a country where they could enter easily and live freely.

The answer, many found, was a long-haul flight to the other side of the world.

“When I told my parents I am moving to Argentina, they were like — where is that,” said Anton Floretskii, 29, a programmer from Tolyatti, an industrial city in western Russia. “I explained it’s in the Southern Hemisphere. That they have completely different stars.”

Floretskii said that in Russia, he had been targeted, beaten and shamed for being gay. Now, he wore a tank top reading “my boyfriend is gay” and went to the recent Pride celebration alongside scores of strawberry blond Russians in lace corsets and lipstick singing Argentine gay anthems and sharing empanadas.

“It’s kind of random,” Floretskii said. “Argentina was never on the map.”

Putin has in recent years pursued an increasingly harsh crackdown on LGBTQ+ rights in a campaign of oppression that has accelerated since the start of the war in Ukraine in February 2022. In 2023, the Russian Supreme Court designated the “international LGBTQ movement” as an “extremist organization” on par with the likes of al-Qaida, leading to a new wave of repression.

Many gay Russians said it was the culmination of years spent living in fear. Lesbians wore wedding rings to pretend to have husbands, while gay boys were assaulted in malls over their dyed hair.

Some decided to leave.

Floretskii stumbled across Argentina as a possible destination in 2022, when it was included in a Google document shared among gay Russians listing possible countries to where they might immigrate.

Argentina offered strong protections for LGBTQ+ people, including same-sex marriage and gender self-determination.

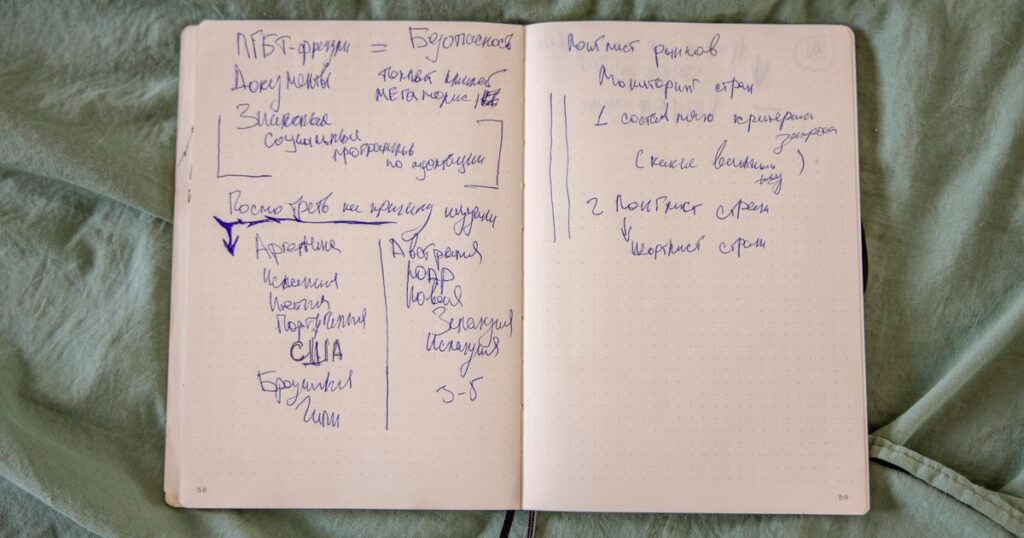

Georgii Markelov, 27, a social media manager from Moscow, jotted Argentina down in his diary alongside a dozen other countries known for respecting human rights and where Russians could enter without a visa.

Giordani Taldyki, 27, a psychologist from Moscow who had first moved to Bangladesh, read Argentina’s Constitution in a park in Dhaka, the Bangladeshi capital.

“They have immigrant rights in the Constitution,” Taldyki said. “I was like, OK, I really like it.”

The Argentine Constitution, which was frequently mentioned by LGBTQ+ Russians in Buenos Aires as a key reason for moving there, states that it welcomes “all men in the world who want to live on Argentine soil.”

The constitution was adopted in 1853, when Argentina was trying to populate a vast, sparsely inhabited territory and swung its doors open to Europeans. Italians, Spaniards and Eastern European Jews, among others, arrived by the shipload and turned Buenos Aires into one of the great global immigrant hubs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The nation’s liberal immigration policies later attracted war refugees and also high-ranking Nazis seeking to disappear.

Argentina had previously welcomed Russian immigrants, including political dissidents from the former Soviet Union and those seeking refuge after its collapse.

The latest wave started after the war against Ukraine, with Argentina’s government recording more than 120,000 Russian arrivals since 2022. The group included many pregnant Russian women hoping to secure a better future and a passport with fewer restrictions for their children. That trend gained national attention in Argentina, but less noticed was the parallel, quieter wave of gay and transgender Russians seeking political asylum.

“Russians were coming, like, coming and coming and coming,” said Anna Sokolova, 43, who is originally from Siberia and runs a dog training business in Buenos Aires with her wife. “It was like a snowball.”

Mariano Ruiz, the director of a group supporting LGBTQ+ asylum-seekers in Argentina, said it had helped more than 1,800 Russians since the war began. Argentina’s allure partly rests with its history: It was the first country in Latin America and one of the first in the world to approve same-sex marriage, in 2010. It also passed landmark legislation allowing people to change their gender on official documents without medical or judicial approval.

“I can be a trans girl, I can be myself and I don’t feel judged,” said Alisa Nikolaev, 24, who grew up in Siberia and moved to Argentina last year.

Still, Argentina’s inclusivity is not a priority for its right-wing president, Javier Milei, who has railed against what he calls “gender ideology” and has tightened immigration rules.

While he has not sought to overturn marriage equality, his government has imposed sweeping austerity measures that have strained public health programs, including those that provide hormone therapy and HIV medications.

The tension was palpable at the Pride celebration, where among makeshift street grills selling meat sandwiches dripping with fat, attendees wore caps reading, “Make Argentina Gay Again.”

For many queer Russians, the outspokenness was reassuring, and unexpected. “I was so happy,” Taldyki said. “Here, people fight.”

There was much more he, and others, cherished about Argentina.

Taldyki said he loved when people asked him, “Do you have a girlfriend or boyfriend?” He loved when he saw a trans cabdriver and when he stopped being reminded of his sexuality.

“Sometimes, here, I forget I’m gay,” he said.

Floretskii loved walking into a salon and finding a gay hairdresser and Lady Gaga blasting from the speakers. “I was like, oh my God, am I in a country where this is normal?”

Sokolova said she loved when doctors at the reproductive clinic where she was undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment asked her why she did not come with her wife, Antonina Lysikova, 37.

When they filmed a family video this year, Lysikova said, the videographer they had hired asked why they did not show any physical affection.

“We just understood that we are accustomed not to hug each other in society,” Lysikova said.

Still, no matter how integrated into Argentine society many Russians felt, they were still haunted by the idea that they had to travel thousands of miles from home to enjoy basic rights.

“The bad part of immigration is that our country is not interested in us at all,” Lysikova said. “Maybe Argentina will be interested in us, but Russia never. It doesn’t matter how much money we earn, how smart we are. Russia doesn’t want us.”

As the sun set on Pride day in Buenos Aires and prepared to rise over Moscow, Russian lesbian couples in rumpled skirts and smudged makeup after a full day of revelry slow-danced inside a beaux-arts apartment hosting a Russian Gay Pride after-party. One woman wiped away tears.

The Russian DJ played “I Kissed a Girl” by Katy Perry. Next to the dance floor was a room showcasing merchandise by Russian LGBTQ+ artists — including T-shirts and tote bags — as well as a charity box for donations for a transgender Russian who recently died by suicide in Argentina.

Igor Muzalevskii, 26, a developer from St. Petersburg, stood on the apartment’s balcony in a glittery silver vest and fishnet stockings. Below him, one of the Pride parade’s last floats passed by in the dark, still packed with people jumping for the sixth consecutive hour. One kept waving a rainbow flag.

“This is why we came,” Muzalevskii said, pointing down. “Now we know that the world can treat you better.”