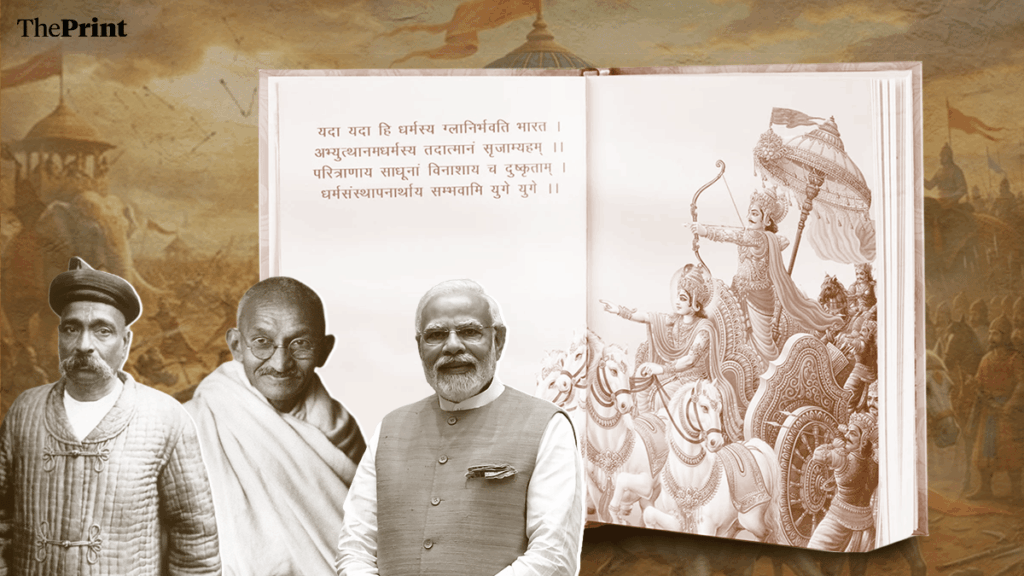

By the late years of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the Bhagavad Gita, the 700-verse meditation in the 1,00,000-verse epic Mahabharat, which had been prized among Hindus for centuries, had been transformed into a talisman for revolutionaries—a religious and philosophical basis for action, importantly violent action, in the political sphere. From Tilak to Aurobindo, revolutionaries, who sought to defeat the British with a tit-for-tat strategy of violence, sourced legitimacy from a specific interpretation of the Gita they propagated.

Almost a century later, the Bhagavad Gita is back at the centre of political action. Last week, over five lakh people, including West Bengal Governor C.V. Ananda Bose, BJP leaders, as well as sadhus and sadhvis from across the state thronged to Kolkata’s iconic Brigade Parade Ground for a collective recitation of the Gita.

“The Gita programme has been taking place for the last three years in Bengal. Just like the Gita had helped unite Hindus during the Independence struggle when the country was being divided on the Hindu-Muslim issue, we need the Gita again today in Bengal,” BJP leader Dilip Ghosh, who had participated in the gathering, told ThePrint. “In Bengal, Hindus are facing the same threat of being turned into refugees in their own land. So Gita is the best way to unite them because firstly, every Hindu irrespective of their sect believes in it, and secondly, because the Gita is set on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, it gives people the urja (energy) to fight.”

“Gita urja, shakti aur sahi ladai ladne ka granth hai (the Gita is a text of energy, strength, and of fighting the right battle),” he said.

Miles from Kolkata, in New Delhi, the Gita was at the centre of Indian diplomacy weeks before that when Prime Minister Narendra Modi gifted a Russian translation of the text to President Vladimir Putin on his visit to India.

An RSS-affiliated writer commented, “The Gita is the most potent soft power weapon India has. It is the face of Hindustan’s spirituality across the world.”

Earlier this month, Union Minister H.D. Kumaraswamy wrote to Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan, urging him to include the Bhagavad Gita in school curriculum—an appeal that prompted Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah to call him a “manuvadi”. The text would steer youth away from the path of drugs, Kumaraswamy had stated.

From Lucknow to Kurukshetra, and Shivamogga to Hyderabad, high-profile sammelans with chief ministers, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat and retired bureaucrats attending, are being organised across the country to discuss and recite the teachings of this timeless text.

What explains this resurgence of the Bhagavad Gita in the political sphere? Is there a concerted attempt to push the text for political and religious mobilisation? Or is this an organic assertion? Moreover, what has the political career of the Bhagavad Gita been in modern Indian history? When did it emerge as a tool for political mobilisation? And was there a difference in how someone like Tilak used the Gita in public life from how Gandhi interpreted the text?

Also read: Why the Bhagavad Gita is set on a battlefield—it has nothing to do with violence

From diplomacy to domestic politics

To begin with, different leaders and writers affiliated with the Sangh Parivar told ThePrint that there is no concerted attempt by the RSS or the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) to organise these events.

However, the main teachings of the Gita—that Bharat’s ethos is one steeped in spirituality and hard power—has been the driving force for not just this government but the Sangh Parivar at large, an RSS leader from Haryana said. Therefore, from Haryana to Bengal to the international stage, “you see the resurgence of the Gita in the last ten years because it is the Gita from which we derive our worldview,” he said.

Moreover, the lucidity of the Gita’s message makes everyone gravitate towards it, said the RSS-affiliated writer quoted above. “The Gen Z, which is obviously facing a vacuum in life, is gravitating to the Gita on its own because of the simplicity of its message. Krishna remains one of the most popular gods, so the Gita has instant resonance,” he said.

Also, for decades, the Bhagavad Gita has had international appeal. “If you have watched Openheimer, you know that even Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, had read and was deeply influenced by the Gita. That gives Indians self-confidence on the international stage, and makes them come closer to realising Bharat’s role as a Vishwa Guru.”

“That is why even when the PM gifts Putin or Obama something, it is not Ramayana or the Shiv Puranas, but the Bhagavad Gita—everyone already knows it,” he said. “Even colonial scholars held it in high regard.”

The internationalisation of the Gita and the ballooning of Hindu self-esteem as a result of it indeed has a long history.

‘Discovering’ the Gita

The early and mid-19th century were a time of European intrigue about ‘native’ Indians. Spellbound Europeans, fascinated by India’s myriad religions, cultures, languages, architecture, sought to frantically retrieve the subcontinent’s past. Religious books were discovered and translated. ‘Origins’ of people and languages were probed. Historical sites were archaeologically examined.

As argued by Manu Pillai in the book Gods, Guns and Missionaries, there was an “unforeseen by-product” of this European “retrieval” of Indian history. Indians’ pride in their own history swelled up rapidly. As Europeans began to get mesmerised by the Indian past, Indians too began to get mesmerised by their own past refracted through the European lens.

The “discovery” of the Bhagavad Gita, translated in English for the first time in 1785, was a case in point. Orientalists, missionaries, colonial officials, romantics—all marvelled at this spiritual text which, unlike any other in the world, was set on a battlefield.

Warren Hastings, one of the earliest and most influential British administrators in colonial India, declared that Gita’s theology was “accurately corresponding” with the fundamentals of Christianity. In his arguably subconscious desire to “discover” the Bible-equivalent in Hinduism, Charles Wilkinson, the translator of the Gita, declared that the text contained all the “grand mysteries” of Hinduism. In the West, the Bhagavad Gita became a sensation—scholars and philosophers hailed it as the window to the wisdom of the East. The centrality of Krishna was further advanced as evidence of the purported monotheism of “uncorrupted Hinduism”.

As Indians began to discover their own past through European translations, Hindus consumed this European-interpreted Bhagavad Gita with renewed interest. The Gita’s new-found prominence inflated Hindu self-esteem at a time they had been disparaged and humiliated for their idolatry by the British.

However, the new-found Hindu pride was not the only “unforeseen by-product” of Orientalist interest in the Bhagavad Gita. By the end of the 19 century, revolutionaries and militant nationalists found in this rediscovered Gita the religious justification for the political violence they increasingly saw as the only means to end colonial rule in India. In Krishna’s exhortation to Arjun to fight the righteous war, they discerned an implicit allegory for their own times: The overthrow of British rule through violence, if necessary.

In the years that followed, revolutionaries held the Gita in one hand, and a revolver in the other. It was an interpretation of the Gita that legitimised, even necessitated holding the revolver.

The problem of the ‘political sadhus’

In the first two decades of the 20th century, as the nationalism of extremists gained ground, the colonial state was reporting a peculiar problem—the problem of the ‘political sadhus’.

In June 1908, the Bombay administration for instance, unearthed secret societies like the Shivaji Club, Khed Club, Belapur Swami Math Club, Pen Club and Abhinava Bharat. In these revolutionary societies, the administration found that “many Sadhus were using Bhagavad Gita for nationalist purposes”.

In 1907, when Keshav Krishnaji Damle, a close friend of Tilak’s, gave lectures on the Gita in various locations, the district magistrate observed, “The lecture is very effective. He preached rebellion with such cleverness that it is doubtful whether the penal code can touch him.”

The political use of the Gita for revolutionary purposes was soon becoming a headache for colonial intelligence across the country. In Bengal, the intelligence noted: “The doing of the Anarchist Society formed by Arabind (Aurobindo Ghosh) and Barindra (Kumar Ghosh) in Maniktola Garden Calcutta… was of religious character, and the people who frequented the garden combined the study of the Gita with the preparations of bombs and explosives.”

Far away in Shimla, the Director of Criminal Intelligence, Shimla wrote in 1910, “These men are invariably Brahmins and being of the superior intellect, they know how to win the people to their cause by touching their susceptibilities. I am firmly of the opinion that these men play more substantial mischief than the more reckless extremist newspapers.”

“What they generally do is this—they select a single passage or verse from some puranas, more especially from the Bhagawad Gita for their theme… (and impress) the advice given by Krishna to Arjun that it is no sin to destroy the enemy, that the destruction of the material or physical body is not the destruction of the Atma of the person destroyed,” he reported. “Then they carefully twist the subject and apply these principles to the present day politics.”

The state scrambled for responses. School syllabi began to be checked to find out whether Bhagavad Gita was taught in moral science class. Schools found to be teaching the Gita were branded the ‘Schools for sedition’. Dramas which made references to Krishna’s advice to Arjun were banned.

Minute details of the ‘political sadhus’ began to be recorded before the Government of India finally enacted the Indian Press Act in 1910. While introducing the Bill, Sir Herbert Risley, the Home Secretary, too could not but mention the Gita. “The dialogue between Arjun and Krishna in the Gita, a book that is to Hindus what the Imitation of Christ is to emotional Christians… (is) pressed into the service of inflaming impressionable minds,” he said.

It was, of course, a deliberate strategy.

In the years of Swadeshi following the Partition of Bengal in 1905, when political activity was under strict surveillance and the repressive capacities of the colonial state on full display, nationalists were desperately looking for methods of mass mobilisation that could escape the state’s panoptic gaze. Theatre, mela songs, bhajan-kirtans and pravachans became their lifeboats.

But the binding force was the Gita. As argued by Dipesh Chakrabarty in Gandhi’s Gita and Politics as Such, it was the Gita through which the nationalists could not only escape state scrutiny, but also press the fact that from the time of the Mahabharat to the 1857 War of Independence, there was “a long tradition of rightful violence in India”. For Swaraj, therefore, Indians only had to turn to their own tradition of rightful violence—a tradition enshrined in the newly interpreted, “revolutionary” Gita.

“The Gita is undoubtedly the most significant spiritual or scriptural primer that Indian leaders used during the freedom struggle,” says Makarand Paranjpe. “Vivekananda, Tilak, Aurobindo, Gandhi, and Vinoba, among others, not only studied it deeply, but wrote commentaries on it. Why? Because they found in the doctrine of ‘karma yoga’ the key to national regeneration,” he said.

“Even Bankim, earlier, suggested that India turn from the effete and romantic Krishna of the Bhakti cult to a more masculine and strategic Krishna of the Gita. We can free ourselves through our own action and works was the idea, not just pray and beseech some divinity or supernatural power.”

Gandhi’s Gita versus Tilak’s Gita

The interpretation of the Gita espoused by Gandhi, however, was distinctly different from Tilak or Aurobindo’s interpretation.

Before the 1880s, the Gita that had been popular among the Sanskritised literati emphasised the idea of renunciation of all action in the world, argues Mark Harvey in The Secular as Sacred?—The Religio-Political Rationalization of B.G. Tilak.

The Gita that had been popular among the rest of the population emphasised the idea of action, but only in the form of devotion to Krishna. Moreover, as mentioned above by Paranjape too, this Krishna was the playful child-god, who did not always come across as the serious, respectable ‘hard god’ involved in ‘realpolitik’.

The revolutionaries sought to change that—a Gita that promoted renunciation had to be replaced by a Gita that promoted action, and violent action, when needed. As argued by Harvey, “Tilak believed that it was in the Gita that the conception of activism (which he called karma-yoga) was carried to its logical conclusion in that Krishna’s exhortations to Arjun to fight should be taken as a rallying cry for Hindus to ‘fight the British by violence if necessary, in order to regain political supremacy’.”

Violent action, according to Tilak, was not immoral by itself as long as it is not pursued with self-interest in mind.

There was yet another ‘problem’ with the existing interpretations of the Gita. It was believed that when Krishna admonished Arjun to fight, it was due to the latter’s very specific caste obligation as a Ksatriya. Tilak sought to generalise the specific caste obligation of Arjun to fight as the obligation of every individual (specifically Hindus) to fight the “right battle”.

Sure enough, Tilak was not the only one to articulate this interpretation of the Gita. A whole generation of revolutionaries now read the Gita this way.

Writing in the journal Bande Mataram in December 1906, Aurobindo Ghosh said, “Gita is the best answer to those who shrink from battle as a sin, and aggression as a lowering of morality… Therefore, says Shri Krishna in Mahabharat, ‘God created battle and armours, the sword, the bow and the dagger.”

Clearly, not rising violently to violence was considered sitting out—an option no longer available to the new-age follower of the Gita.

Gandhi’s interpretation of the Gita was markedly different.

If Tilak’s interpretation of the Gita was “Ye Yatha Mam Prapadyante Tantast–thaiva Bhajammaihyam” (I shall act in the same manner in which others behave with me), Gandhi offered a completely different take on the same text, namely Shatham Pratyapi Satyam (unmindful of any cheating, I shall not leave the path of truth).

Gandhi squarely opposed what he called Tilak’s “tit-for-tat” approach to politics.

As argued by Chakrabarty, Gandhi borrowed the term Swaraj from the lexicon of his adversaries, including Tilak, and said that indeed it is the satyagrahi’s dharma to work ceaselessly towards it. However, if for Tilak, Swaraj had to be won at any cost—a sentiment betrayed by one of the most popular slogans attributed to him, “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it”—for Gandhi this contravened the other principle of the Gita, that is action with non-attachment. In Gandhi’s reading of the Gita then one could not get too attached even to Swaraj as that could lead the satyagrahi astray, away from rightful action.

The RSS leader from Haryana acknowledged that indeed there have been different interpretations of the Gita in the past. “But if you read Tilak’s Gita Rahasya (Tilak’s own take on the Bhagavad Gita), he clearly states that Gita is not a pot of jugglery that anyone can extract any meaning from it… We believe the same.”

(Edited by Viny Mishra)

Also Read: What machine learning can tell us about Bhagavad Gita