China’s ambitious efforts to combat desertification and environmental degradation through large-scale tree planting are beginning to show unexpected consequences, as highlighted in a recent study published on October 4 in the journal Earth’s Future. The research examines how these extensive regreening projects have affected the country’s water cycle, redistributing water across vast regions in ways scientists are still trying to fully understand.

The Scope of China’s Re-Greening Initiatives

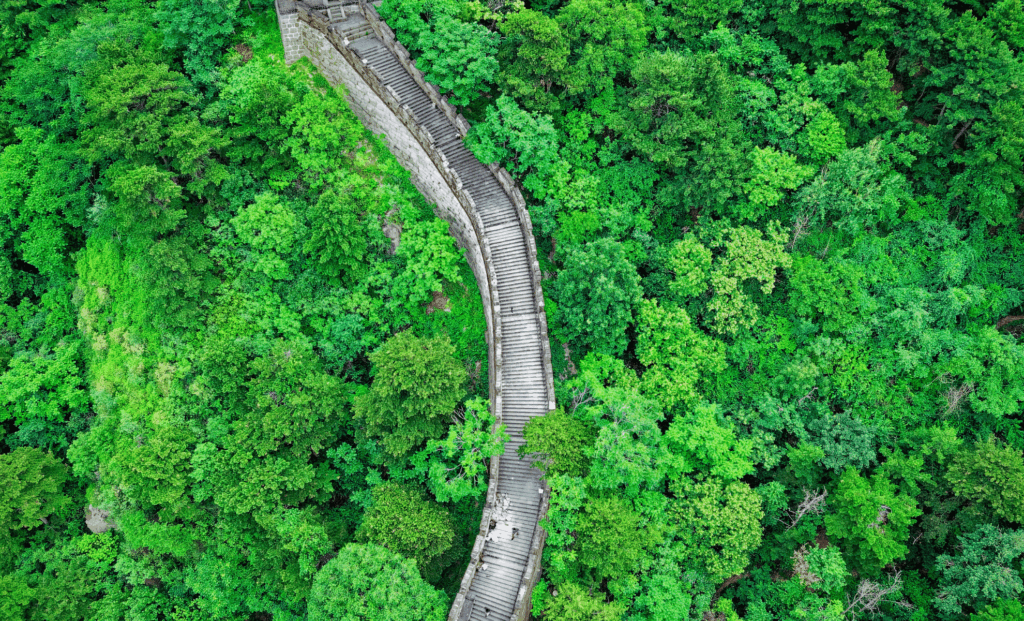

For decades, China has invested heavily in reforestation and land restoration projects, aiming to slow desert expansion and restore ecological balance. The most well-known of these initiatives is the Great Green Wall, which has aimed to transform the northern, arid regions by planting trees to encircle the vast Gobi Desert. In addition, the Grain for Green Program and the Natural Forest Protection Program have been part of China’s broader efforts to restore ecosystems and increase forest cover. These projects have not only altered the landscape but have triggered profound shifts in the local water cycle.

According to the research, changes in vegetation cover, particularly in regions like the Loess Plateau, have redistributed water in unexpected ways.

“We find that land cover changes redistribute water,” explained Arie Staal, an assistant professor of ecosystem resilience at Utrecht University, a co-author of the study to LiveScience, “China has done massive-scale regreening over the past decades. They have actively restored thriving ecosystems, specifically in the Loess Plateau. This has also reactivated the water cycle.”

However, while these efforts have increased the country’s overall greenery, they have also resulted in unforeseen consequences regarding water availability, particularly in regions where water is already scarce.

Evapotranspiration and Its Impact on Water Availability

One of the key findings of the study, published in the journal Earth’s Future., is the increase in evapotranspiration. This term refers to the process by which water is lost to the atmosphere, primarily through the combined actions of evaporation from soils and transpiration from plants. According to Staal, both grasslands and forests tend to increase evapotranspiration, but the effect is especially pronounced in forests, where the roots of trees can access deep water reserves during dry spells.

“Both grassland and forests generally tend to increase evapotranspiration,” Staal said. “This is especially strong in forests, as trees can have deep roots that access water in dry moments.”

This heightened evapotranspiration has led to a net loss of water in regions that have experienced significant afforestation and grassland restoration. While it is true that China’s efforts have activated a more dynamic water cycle, this increased activity has not always translated into greater water availability.

“Even though the water cycle is more active, at local scales more water is lost than before,” Staal noted.

This has implications for how China manages its already unevenly distributed water resources, as increased water loss from these regions could exacerbate water scarcity issues in the future.

Regional Variations and the Uneven Distribution of Water

The study found that the changes in China’s water cycle are not uniform across the country. In particular, the research highlighted the disparity between regions in the east and north. While the eastern monsoon region saw a decrease in water availability due to increased evapotranspiration, the Tibetan Plateau experienced a modest increase in precipitation. However, this increased precipitation was not enough to offset the increased water loss in the affected regions. As a result, China’s north, which is already home to 46% of the population and 60% of the arable land, has seen a disproportionate effect from these changes in the water cycle.

The uneven distribution of water in China has long been a challenge, with the northern regions facing severe water shortages. The study’s findings suggest that China’s large-scale re-greening projects could further strain the country’s water resources if water redistribution patterns are not taken into account. As Staal pointed out,

“Even though the water cycle is more active, at local scales more water is lost than before,” which could worsen the already critical water shortage in the north.

The study’s conclusions call for a reassessment of how China, and other countries with similar initiatives, manage their water resources in the face of large-scale environmental restoration projects.