TORONTO — Measles cases in Canada have far surpassed those in the United States as health officials in Alberta, a western province that has become a hot spot for the outbreak, have urged the premier to declare a public health emergency to stave off infections.

Canada’s public health agency has recorded about 4,200 measles cases this year, more than three times as many as the 1,300 cases recorded in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC has also ranked Canada among the top 10 countries with the highest number of measles cases. It is the only Western nation on the list.

Alberta, which has low measles vaccine rates, has recorded about 1,600 cases. The largely conservative province has a deep and vocal level of skepticism about the public health system and vaccines, with many people mirroring some of the arguments made in the United States by the health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

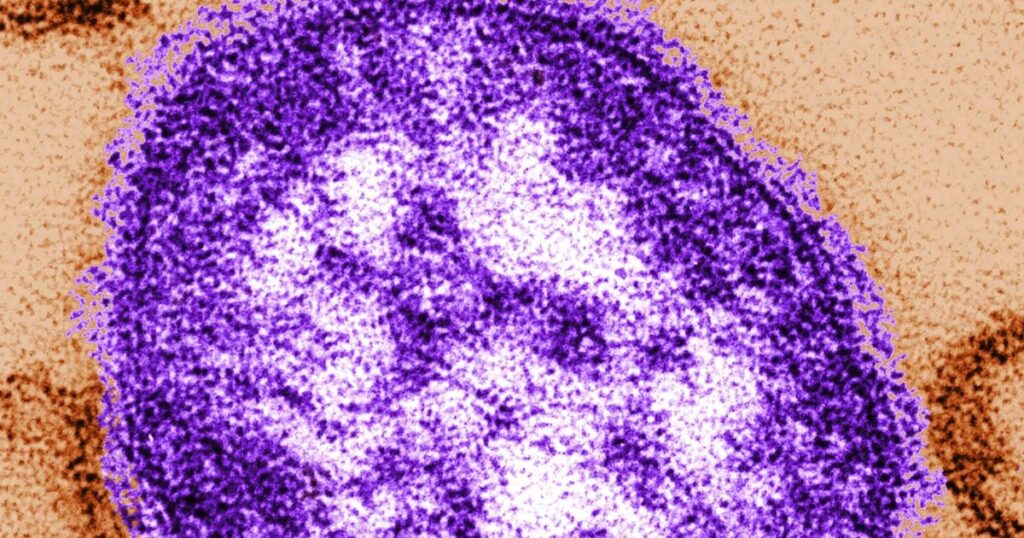

Measles is an airborne virus and one of the world’s most infectious diseases, causing flu-like symptoms and a rash. Severe cases can lead to hearing loss, pneumonia or swelling in the brain. Three people have died in the United States, while in Canada there has been one death, a premature baby who had contracted the virus in the womb.

The spread of measles has slowed in Ontario, the province with the largest number of cases. But health professionals say the opposite is true in Alberta, and many are criticizing the provincial government’s public health response.

“Our performance is so bad that we have more cases in a population of 5 million than the United States has in a population of 340 million,” said Dr. James Talbot, a former chief medical officer of health in Alberta.

Vaccination rates among children have fallen globally since the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a study published this month in The Lancet, a medical journal.

Canada has been part of the trend. In 2021, 79% of children in Canada were vaccinated against measles by their seventh birthday, down from about 86% in 2013, according to federal data.

But vaccine skepticism in Alberta has become more entrenched in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Canada enforced mandatory vaccination requirements for travel. Alberta became an epicenter of pushback against the mandates and many of the leaders of protests that paralyzed Ottawa, the country’s capital, for weeks came from the province.

Unlike Ontario and other provinces, Alberta does not have mandatory immunization requirements for school enrollment.

Canada’s measles outbreak began in October, in the Atlantic province of New Brunswick, and was spread by an international visitor at a Mennonite gathering, according to health officials. That outbreak led to more cases in Ontario, with measles disproportionately affecting Amish, Mennonite and other Anabaptist communities, according to Dr. Kieran Moore, the province’s top doctor.

Health officials in Alberta have directly linked some outbreaks to Mennonite communities.

The Mennonite faith does not have any doctrine prohibiting vaccinations. But many adherents avoid interacting with the medical system and follow a long tradition of natural remedies.

Provincial figures show that about 71% of children in Alberta are fully vaccinated by the age of 7. Some of the hardest-hit parts of Alberta have immunization rates of less than 50%, well below the 95% threshold for herd immunity, said Dr. Craig Jenne, a professor at the University of Calgary who studies infectious diseases.

Several public health experts have criticized the province for its response and are calling on it to declare a public health emergency.

“There’s no indication it is slowing or turning around,” Jenne said. “Clearly, whatever is being done now is not sufficient to bring this back under control.”

While health care in Canada is largely the purview of provinces, the federal government has focused on fighting misinformation around measures like vaccinations, said Dr. Howard Njoo, Canada’s interim chief public health officer.

“We’ve learned a lot in terms of how to address, I would say, a trust issue,” Njoo said.

Alberta Health Services, the health agency, has placed restrictions on visitors in health care settings used by vulnerable patients, including some cancer wards.

To assist with tracing transmissions, local health officials have issued notices in places such as Walmarts, health centers and grocery stores, where people had gone who were later confirmed to have been infected with measles.

But those public alerts have noticeably slowed as health officials have become overwhelmed, said Dr. Lynora Saxinger, an infectious diseases specialist, at a news conference this month organized by the Alberta Medical Association, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“The volume is simply too high for them to be able to catch up,” said Saxinger, adding that an overload of cases will likely also start putting pressure on hospitals. “We’re probably seeing, to some extent, the tip of the iceberg.”