PARIS — The four thieves arrived on the south side of the Louvre on Sunday morning at 9:30 and pulled a truck up on the sidewalk, right next to the museum walls. They posed as workers, wearing yellow vests and setting out traffic cones.

To anyone strolling along the banks of the Seine, just across the road, it might not have been immediately apparent that the setup was a ruse and that a daring robbery was underway. Workers are a common sight around the Louvre, an ancient, sprawling former palace, whose basic upkeep and renovations make it a constantly transforming construction site.

But inside the museum, where visitors were already snaking their way through more than 8 miles of exhibition space, the drama that was unfolding would soon become clear. Two of the thieves used an electric ladder attached to their truck to reach the Apollo Gallery, with its treasury of priceless crown jewels, then used power tools to break through a window.

An alarm was immediately issued to the Louvre’s security command center, which contacted the police, according to Laurent Nuñez, the interior minister, speaking to LCI television Monday.

The police were on their way within minutes, he said, but when they arrived, the masked intruders had already jumped on two motor scooters and taken off. In their haste, the intruders dropped a crown featuring 1,354 diamonds, 1,136 rose-cut diamonds and 56 emeralds. They also left behind a yellow vest and a bottle of fluid that they had used to douse part of the truck as they tried to set it on fire, according to the Paris prosecutor’s office.

But they made off with eight precious pieces of jewelry, including a royal sapphire tiara and a royal emerald necklace with its matching earrings.

The robbery — the stuff of movies — has raised significant questions about whether one of the world’s most famous museums could have been better protected from a crime some politicians have suggested was both a tragedy and a national embarrassment.

For the moment, officials say they are working on the basis that the culprits are most likely members of a criminal gang, of a kind that experts say would probably be more interested in breaking down the stolen jewels for resale than for their artistic value. Officials are also zeroing in on how the museum’s alarm systems work.

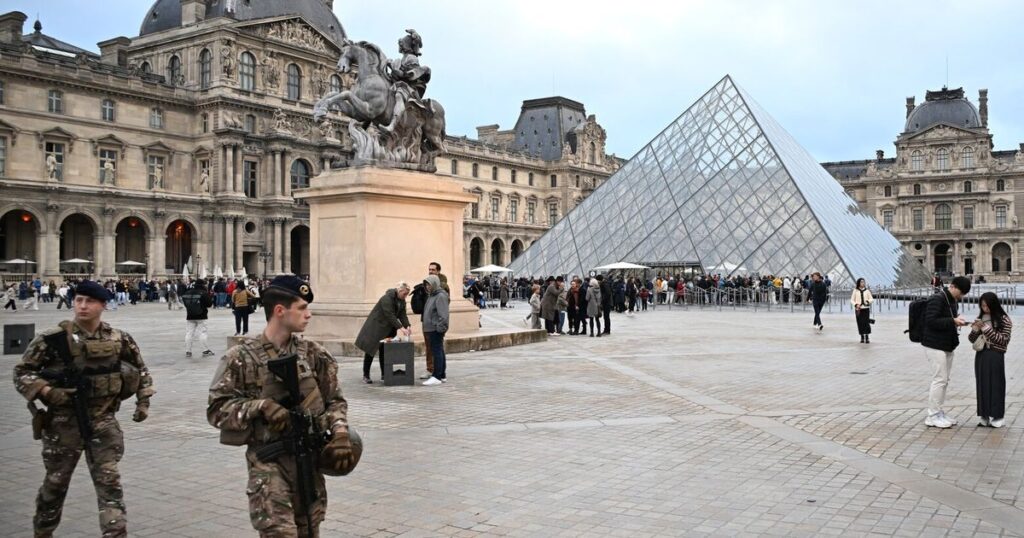

Nuñez said that police patrols, which focus mostly on the Louvre’s crowded central entrance, were not near the thieves’ truck. And while the museum is surrounded by cameras, he said there were not enough officers to continuously monitor the feeds.

Vernon Rapley, a museum security consultant, said that institutions adjacent to streets they do not control, like the Louvre, rely more on quick police reaction.

Labor unions at the Louvre said they had warned that continual renovations, repair work and scaffolding for fundraising events done on or around the museum made it hard for employees to spot suspicious behavior.

“The more we have exterior people working around the Louvre, the harder it is to differentiate who should be there,” said Julien Dunoyer, a leader with the Louvre unit of the SUD union, who has worked as a security agent there for 21 years.

On Monday, parts of an unfinished report on the museum by France’s national auditor that had been ordered before the theft were leaked to French news outlets. The auditor found that 75% of the Louvre’s Richelieu wing had not been covered by video surveillance and that a third of the rooms in the Denon wing had no surveillance cameras. That wing is where the burglars struck, although officials said the refurbished gallery they targeted did have cameras.

The report also criticized delays in updating the museum’s security system.

The auditor confirmed the existence of the report to The New York Times but declined to share it.

The Louvre has not publicly addressed the findings. But in an email to staff members after the burglary that a union leader shared with the Times, the head of the Louvre, Laurence des Cars, said they could count on her “determination in this hardship.”

“When I took office, I warned of the need to strengthen our security architecture,” des Cars said in the email. She added that police had carried out “detailed studies” at her request and that the recommendations would be put in place. She gave no details. (Many museums are wary of sharing details of security plans, even with some staff, for fear of leaks.)

Still, labor unions at the museum said technical and staffing issues, particularly among security guards, had gone largely unaddressed for years.

“It’s the entire surveillance system of the museum that is obsolete today,” said Alexis Fritche, general secretary of the culture section of CFDT, a national labor union. “There is a lack of staff to obviously deal with surveillance, but there is also a lack of staff for evacuation in case of difficulty.”

Security staff members at the Louvre were reduced to 856 agents in 2023 from 994 in 2014, according to Dunoyer.

But it is not clear whether more agents in the Apollo Gallery or even more security cameras would have prevented the theft.

“Once they are inside, it’s already too late,” Dunoyer said.

When there is an intrusion, the museum’s protocol is to evacuate rooms and usher visitors to safety, “definitely not put yourself in danger’s way by going toward the intruders,” said Sarrah Abdelhedi, an SUD leader who has worked at the Louvre in security for 17 years. That was what guards did once the intruders had entered the gilded hall, according to the Culture Ministry.

Still, union representatives said a lack of security agents may have sent a signal of vulnerability to potential criminals.

“These are weaknesses that can be spotted by people who are looking for opportunities to carry out operations like this,” Dunoyer said.

Once outside, security guards chased away the thieves who were attempting to light their truck on fire, Rachida Dati, France’s culture minister, told French television crews Monday.

Security officials at the museum, who are not armed, were so shaken by the brazen heist that they refused to work Monday until they heard from the museum’s director what reinforcements would be put in place, according to Abdelhedi, the union leader.

A spokesperson for the Louvre said the closing was “to allow museum management to discuss the situation with staff.”

Dati said that at least three security audits since 2022 had been factored into plans to overhaul the Louvre, which were announced by President Emmanuel Macron this year. She said security control rooms were being upgraded and a new central control room was being created.

“We are in the process of equipping virtually all rooms with video surveillance and new technologies,” she told CNews television. “We are completely overhauling the digital and IT network, which was totally obsolete, involving 450 kilometers of cables.”

“This cannot be done in 24 hours,” she added, “and it cannot be done by just anyone. It takes time and money.”

Still, several experts noted that it is difficult to protect a medieval palace-turned-museum that was not originally designed to house tens of thousands of precious artworks, nor to welcome nearly 9 million visitors a year.

“The Louvre Museum wasn’t built with an obsession over security in mind,” said Christian Flaesch, the former head of the Paris police criminal investigations department. “It’s a very old building with many people who move through it every day, at different times and with different clearances.”

And it’s also possible that the thieves simply outsmarted whatever safeguards there were, including by carrying out their operation in daylight — what Rapley, the museum security consultant, called a counterintuitive strategy.

“Criminals have tended to attack at night, believing that’s when security is at its weakest,” said Rapley, the former leader of the Scotland Yard art squad. Instead, he said, Sunday’s robbers escaped into morning traffic.

In daytime, he said, “You can disappear a lot easier than if you do it at 4:30 a.m. and stick out like a sore thumb.”