The findings, led by a team at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, represent the oldest direct measurements ever obtained from Earth’s ancient atmosphere. More than just a scientific milestone, they offer a new lens through which to examine a mysterious chapter of planetary evolution, when Earth seemed calm, but may have been quietly preparing for biological complexity.

Most of what researchers previously understood about the Mesoproterozoic Era came from indirect geological indicators and theoretical climate models. But the work of graduate student Justin Park and Professor Morgan Schaller changes that by offering actual samples of ancient air, frozen in time in salt left behind by a prehistoric lake. This new window into the planet’s deep past may reshape how scientists interpret early atmospheric conditions, and the slow rise of complex life.

1.4-Billion-Year-Old Halite Offers Direct Evidence of Ancient Air Composition

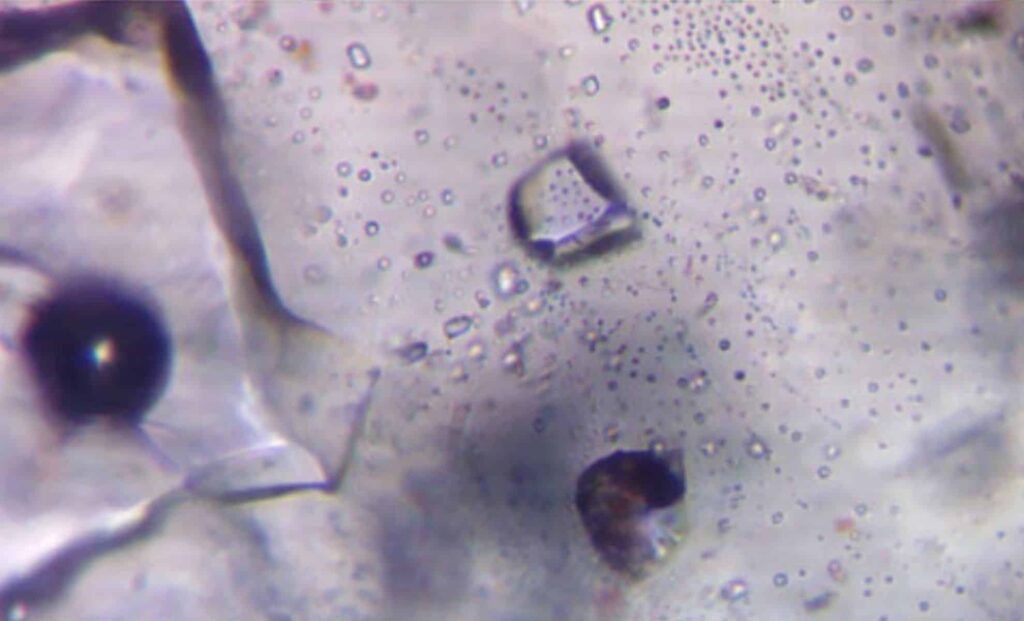

More than a billion years ago, a shallow, subtropical lake evaporated under the sun’s heat across what is now northern Ontario. In its place, it left behind crystals of halite, or rock salt. Some of those crystals trapped tiny pockets of brine and air as they formed, fluid inclusions that, once buried and sealed in sediment, remained untouched for over a billion years. These inclusions have long been suspected to contain gases from early Earth’s atmosphere, but measuring them has been notoriously difficult.

“It’s an incredible feeling, to crack open a sample of air that’s a billion years older than the dinosaurs,” said Justin Park, the graduate researcher who led the analysis. According to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Park developed new methods and used custom-built lab equipment to isolate and measure the gases inside the crystals with unprecedented precision.

The results revealed oxygen levels at 3.7% of modern atmospheric concentrations, a number that exceeds many past estimates for this era and is sufficient, at least transiently, to support simple multicellular life. It’s a stark contrast to the long-standing assumption that the Mesoproterozoic atmosphere was perpetually low in oxygen, part of what gave the “Boring Billion” its nickname.

Surprising Carbon Dioxide Levels Explain a Stable Climate Under a Faint Sun

Equally striking were the carbon dioxide concentrations measured in the ancient inclusions, ten times higher than current atmospheric levels. According to the same study published in PNAS, this high CO₂ would have significantly warmed the planet, offering a likely explanation for the absence of widespread glaciation during the Mesoproterozoic despite a much dimmer sun at the time.

These findings directly challenge earlier models that assumed lower CO₂ levels and struggled to explain why Earth didn’t freeze. The salt crystals themselves also provided temperature indicators, which, when combined with gas measurements, point to a milder, more stable climate than previously thought, comparable in some respects to today’s global temperatures.

Professor Schaller emphasized the significance of this new data, stating, “We’ve never been able to peer back into this era of the Earth’s history with this degree of accuracy. These are actual samples of ancient air!”

A Moment of Atmospheric Change Amid a Billion-Year Lull

Despite the era’s reputation for geological and biological stagnation, these findings suggest that brief atmospheric shifts, like the one captured in the Ontario salt, may have punctuated the long quiet of the Mesoproterozoic. “The sample captures just a snapshot of geologic time,” said Park, pointing out that what they observed could be a transient oxygenation event, not a lasting atmospheric condition.

According to the researchers, the rise of red algae, which appeared around this same time, could have contributed to the higher oxygen levels recorded. These simple organisms remain key oxygen producers on the planet today, and their evolutionary emergence may have played a role in pushing atmospheric conditions toward greater habitability.

Whether this was a rare spike or part of a broader trend remains unclear. But for now, the Ontario halite crystals offer the first clear glimpse into a moment when Earth’s air held the ingredients for life far more complex than the microbial world that then dominated the planet.