JERUSALEM (AP) — After 800 years of silence, a pipe organ that researchers say is the oldest in the Christian world roared back to life on Tuesday, its ancient sound echoing through a monastery in Jerusalem’s Old City.

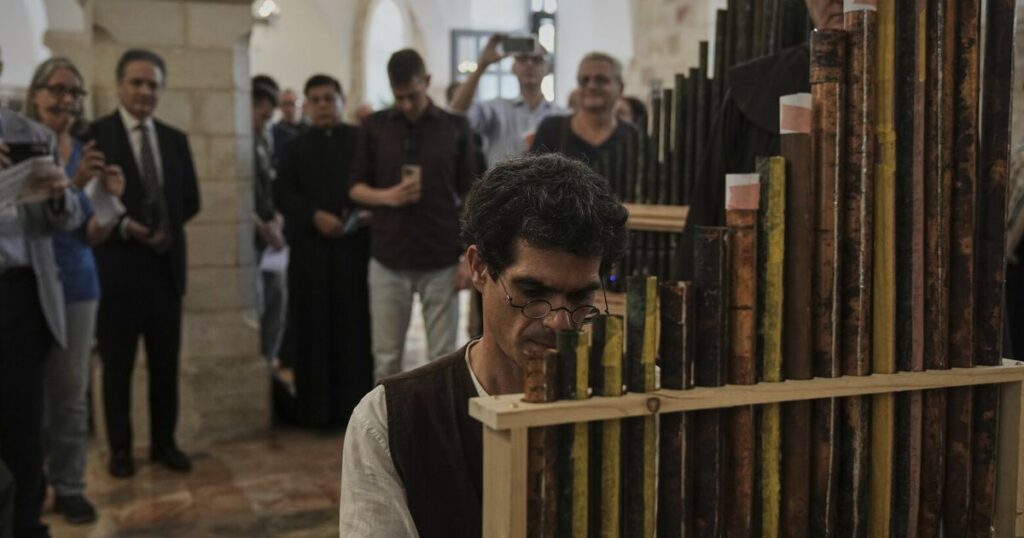

Composed of original pipes from the 11th century, the instrument emitted a full, hearty sound as musician David Catalunya played a liturgical chant called Benedicamus Domino Flos Filius. The swell of music inside Saint Saviour’s Monastery mingled with church bells tolling in the distance.

Before unveiling the instrument Monday, Catalunya told a news conference that attendees were witnessing a grand development in the history of music.

“This organ was buried with the hope that one day it would play again,” he said. “And the day has arrived, nearly eight centuries later.”

From now on, the organ will be housed at the Terra Sancta museum in Jerusalem’s Old City — just kilometers (miles) from the Bethlehem church where it originally sounded.

Researchers believe that the Crusaders brought the organ to Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus, in the 11th century during their period of rule over Jerusalem. After a century of use, the Crusaders buried it to protect it from invading Muslim armies.

There it stayed until 1906, when workers building a new Franciscan hospice for pilgrims in Bethlehem discovered it in an ancient cemetery.

Once full excavations were conducted, archaeologists had uncovered 222 bronze pipes, a set of bells and other objects hidden by the Crusaders.

“It was extremely moving to hear how some of these pipes came to life again after about 700 years under the earth and 800 years of silence,” said Koos van de Linde, organ expert who participated in the restoration. “The hope of the Crusaders who buried them — that the moment would come when they would sound again — was not in vain.”

A team of four researchers, directed by Catalunya, set out in 2019 to create a replica of the organ. But along the way, said Catalunya, they discovered that some of the pipes still function as they did hundreds of years ago.

Organ builder Winold van der Putten placed those original pipes alongside replicas he created based on ancient organ-making methods, some of which were illuminated by close study of the original pipes. The originals, making up about half of the organ, still bear guiding lines made by the original Ottoman craftsmen and engraved scrawls indicating musical notes.

Alvaro Torrente, director of the Instituto Complutense De Ciencias Musicales in Madrid — where Catalunya undertook the project — compared the discovery to “finding a living dinosaur, something that we never imagined we could encounter, suddenly made real before our eyes and ears.”

Researchers hope to finish restoring the entire organ and then create copies to be placed in churches across Europe and the world so its music is accessible to all.

“This is an amazing set of information that allows us to reconstruct the manufacturing process so that we can build pipes exactly as they were made,” about a thousand years ago, said Catalunya.