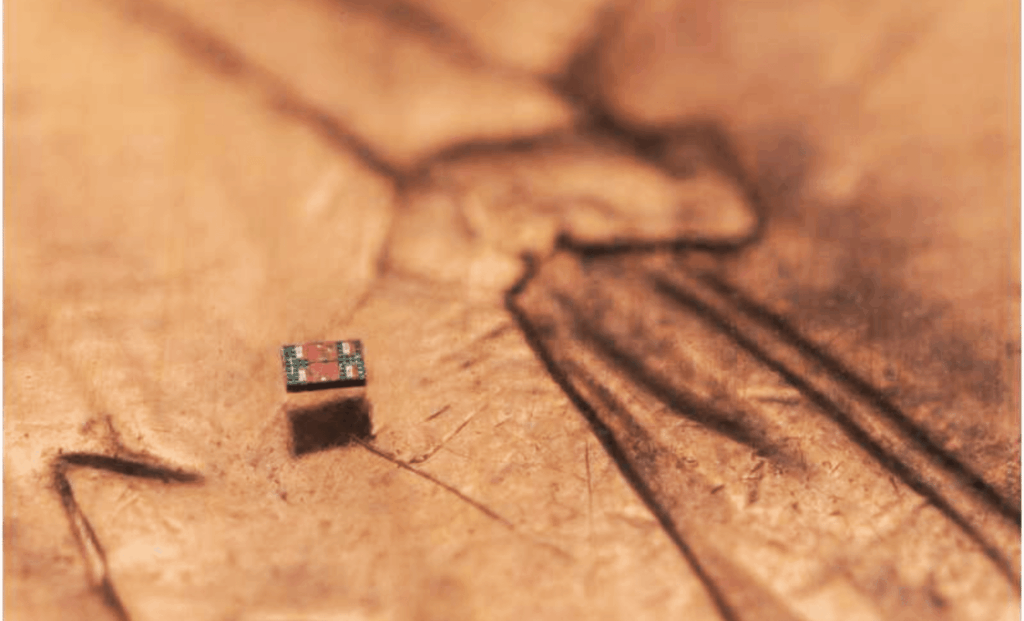

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan have developed the smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots ever created. These microscopic marvels are not only tiny but also capable of swimming, sensing temperature, and responding autonomously to their surroundings. This achievement marks a significant milestone in the field of robotics and could pave the way for a wide range of applications in medicine, manufacturing, and environmental monitoring.

The Challenge of Creating Autonomous Robots at the Microscale

For decades, scientists have struggled to create functional robots smaller than a millimeter. Traditional robotics, which often rely on physical limbs or rigid structures, face significant challenges at the microscale. As Marc Miskin, Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, explains,

“Building robots that operate independently at sizes below one millimeter is incredibly difficult. The field has essentially been stuck on this problem for 40 years.”

At such small sizes, the forces governing movement change drastically. Instead of gravity and inertia, tiny robots are more influenced by drag and viscosity, forces that are often harder to overcome in micro-sized systems.

“If you’re small enough, pushing on water is like pushing through tar,” says Miskin. At this scale, typical methods of propulsion, like legs or rotating wheels, become impractical. Consequently, the team had to develop an entirely new approach to robot movement that would allow these tiny machines to move effectively within the liquid environments where they operate.

A Unique Propulsion System for Microscopic Movement

The breakthrough comes from the robots’ innovative propulsion system. Unlike traditional robots that rely on mechanical movement, these microbots generate an electrical field that nudges ions in the surrounding solution. These ions, in turn, push on water molecules, creating movement. “It’s as if the robot is in a moving river,” says Miskin, “but the robot is also causing the river to move.” This design not only allows the robots to swim without the need for moving parts but also provides durability, as the robots are far less prone to mechanical failure.

This type of propulsion system also means the robots can be manipulated with extreme precision. The lack of moving parts reduces the chance of wear and tear, allowing the robots to be transferred from one sample to another without damage. “You can repeatedly transfer these robots from one sample to another using a micropipette without damaging them,” Miskin notes. This level of durability makes the robots suitable for delicate applications in fields such as cellular monitoring, where handling with care is crucial.

Autonomous Decision-Making Powered by Tiny Computers

To function independently, the robots need more than just propulsion systems; they require a brain capable of making decisions based on environmental input. This is where the collaboration between Penn Engineering and the University of Michigan truly shines. Researchers at Michigan developed the world’s smallest onboard computers, which fit into the tiny robots without sacrificing their functionality. The challenge, however, was the limited power available to the robots, as their solar panels only produce 75 nanowatts; over 100,000 times less than the power consumption of a smart watch.

“The key challenge for the electronics,” says David Blaauw from the University of Michigan, “is that the solar panels are tiny and produce only 75 nanowatts of power. That is over 100,000 times less power than what a smart watch consumes.” To overcome this, the team had to rethink the computer architecture entirely. The result was a processor that consumed much less power, enabling the robot’s onboard electronics to function effectively on such a minimal energy budget.

“We had to totally rethink the computer program instructions,” says Blaauw, “condensing what conventionally would require many instructions for propulsion control into a single, special instruction to shrink the program’s length to fit in the robot’s tiny memory space.” This breakthrough in miniaturization of both power and memory makes these robots not just autonomous but also capable of complex tasks such as sensing temperature and adjusting their behavior accordingly.

Versatile Applications in Medicine and Beyond

The development of these robots is not only a technological feat but also a step toward transforming various industries. In medicine, for example, these robots could be used to monitor the health of individual cells or detect changes in temperature, providing valuable insights into cellular activity. The robots’ ability to sense temperature to within a third of a degree Celsius makes them ideal candidates for applications that require precision and sensitivity.

“In the future, we could deploy these robots in swarms to perform complex tasks,” says Miskin. “Each robot could have a different function, making them ideal for multi-tasking experiments or monitoring large populations of cells.” Such capabilities could revolutionize drug testing, environmental monitoring, and even the way we approach micro-manufacturing.

The collaboration between Penn and Michigan, as detailed in Science Robotics and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, demonstrates not only the feasibility of microrobots but also opens up endless possibilities for further innovations. These microbots could be the key to tackling some of the most pressing challenges in fields like health diagnostics, environmental sensing, and microscale manufacturing.