The increasing demand for valuable metals like cobalt, nickel, and copper is driving corporations to explore the ocean’s abyssal plains. But researchers warn that the machines used to harvest these resources could irreversibly damage ecosystems that remain largely unexplored and poorly understood.

Located in the eastern Pacific, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) spans a vast area of seafloor more than 13,000 feet deep. It is one of the most coveted regions for deep-sea mining due to its abundance of polymetallic nodules, lumps of metal that contain economically important elements. But this resource-rich environment also supports a fragile and little-known web of life. Efforts led by the University of Gothenburg and other institutions are now racing to catalog species before commercial mining begins.

The stakes are high. Many animals found at these depths rely on “marine snow”, organic matter falling from the ocean surface, to survive. Any disruption to the seafloor risks disturbing this delicate nutrient cycle and displacing species that are highly adapted to life in the abyss.

Unprecedented Biodiversity in the Abyss

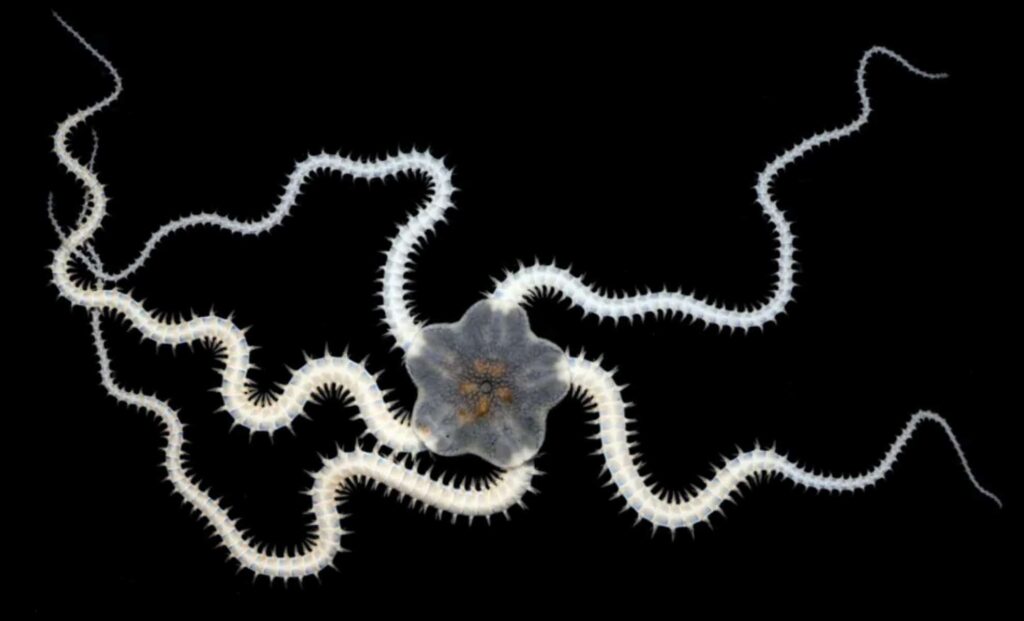

A recent expedition in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) has revealed 788 deep-sea species living in the region, many of them new to science, some only known through DNA. Among them are chimaeras, sea spiders, pink sea pigs, transparent sea cucumbers, and solitaire corals. One group alone, annelid worms, produced 300 new species, according to teams from Gothenburg and the Natural History Museum of London.

These findings emerged as part of a broader effort to assess environmental risks posed by deep-sea mining. Marine biologist Thomas Dahlgren, who participated in the research, said in a study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution that although total species numbers didn’t decline in mining test zones, species dominance changed.

“We found no evidence for change in faunal abundance in an area affected by sediment plumes from the test mining; however, species dominance relationships were altered in these communities, reducing their overall biodiversity,” Dahlgren said.

Such changes may have long-term effects on ecosystem balance, especially given that 74 percent of abyssal life resides in the top layer of sediment, exactly the area most affected by suction-based mining.

Mining Tests Show Severe Local Impact

In 2022, a commercial deep-sea mining test on the Eastern Pacific’s abyssal plain extracted more than 3,000 tons of metal. The suction mechanism used to retrieve polymetallic nodules sent up sediment plumes that settled across the surrounding area, directly impacting seafloor habitats. According to Popular Mechanics, researchers observed a 37 percent drop in macrofauna population density in the area directly skimmed by the mining equipment.

These sediment plumes pose multiple dangers. They can clog or damage the gills and feeding structures of benthic organisms, and their chemical composition may be toxic to many life forms. For species like glass sponges and annelids, which rely on delicate filtration systems, the intrusion of mining debris could be fatal.

Noise from mining equipment is another concern. Marine mammals such as dolphins and whales, although not residents of the ocean floor, could still be disturbed by the intense sound waves generated during extraction operations. While the full impact of noise pollution remains uncertain, its potential to disorient or harm sensitive species is part of a growing list of concerns raised by scientists.

Pressure Mounts for Long-Term Monitoring

Despite the scale of the findings, scientists caution that what has been discovered may represent only a fraction of the true biodiversity in the CCZ. Many organisms may have gone undetected, and some captured specimens failed to survive the ascent to the surface due to the drastic change in pressure. Researchers believe that understanding the effects of sediment plume settlement over time is key to making informed decisions.

“Longer-term monitoring of the impacted sites would enable better evidence on rates of recovery,” the study noted. Unlike areas directly affected by mining tools, plume-settled zones may show ecological changes at a slower pace, making them harder to evaluate in short-term studies.