It’s not a movie. It’s a window into reality, one now rendered by the world’s most powerful supercomputers. This simulation is a major leap toward understanding how the brightest black holes function, including the ones powering ultraluminous X-ray sources and mysterious high-redshift objects observed by telescopes like JWST.

According to a study published in The Astrophysical Journal and led by Lizhong Zhang, a researcher at the Institute for Advanced Study and the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics, this marks the first time full radiation general relativity has been used to simulate luminous black hole accretion flows. Instead of relying on simplified models, the team built algorithms capable of calculating radiation and matter interaction in extreme gravity, solving equations that previously seemed impossible without shortcuts.

Over ten simulations were performed, exploring accretion around stellar-mass black holes from sub-Eddington to 100× Eddington regimes. The results closely match real X-ray data, paving the way to reinterpret how light, energy, and matter behave near black holes.

New Light on Super-Eddington Accretion

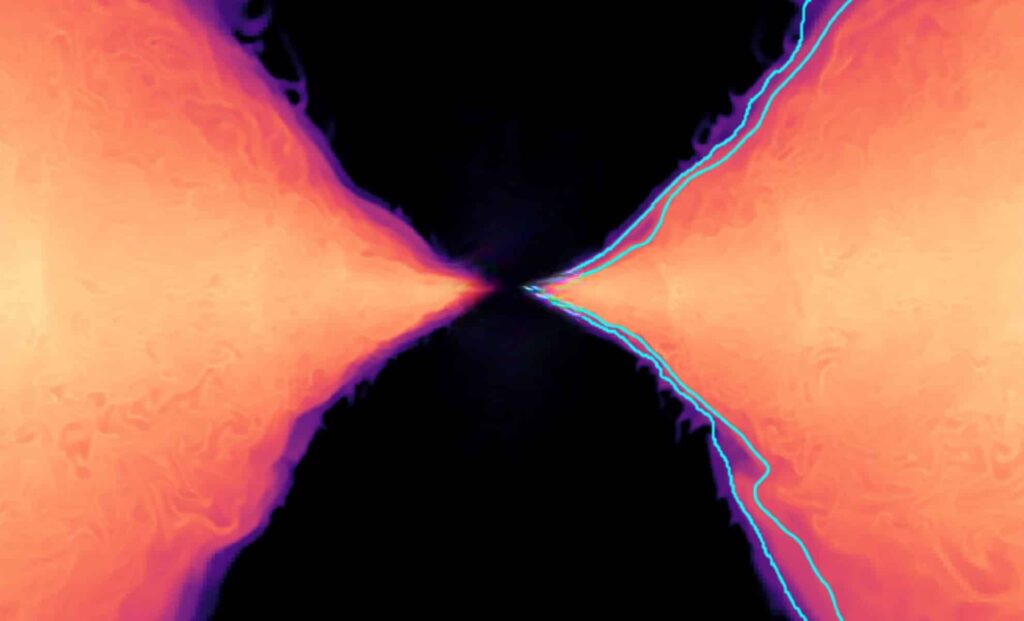

Super-Eddington accretion, where a black hole consumes matter faster than the theoretical radiation pressure limit, was once considered unstable or even impossible. These new simulations challenge that view directly. In cases such as model E88-a3, the accretion disk remains geometrically thick and is supported by radiation pressure. The data show strong turbulence, massive outflows, and the presence of tightly collimated relativistic jets, even though none of the simulations entered the magnetically arrested disk (MAD) state.

Radiative efficiency in these super-Eddington flows plummets to below 0.5%, with most of the energy being carried not by photons, but by kinetic outflows. The emergent radiation is “beamed” into a “narrow cone,” notes the team in the first article of the series, suggesting a mechanism that could explain why ultraluminous X-ray sources (ULXs) appear brighter from certain angles.

According to Zhang, “What’s most exciting is that our simulations now reproduce remarkably consistent behaviors across black hole systems seen in the sky,” including sources like Cyg X-3 and SS 433. The simulations confirm that photon trapping and vertical radiation advection dominate the cooling process, a result consistent with prior non-relativistic models but now confirmed with full general relativity.

Magnetic Topology Changes Everything

One of the more striking outcomes is how the magnetic field geometry at the start of the simulation determines the disk’s evolution. Initial configurations with a single-loop field, which create a net vertical flux at the midplane, give rise to thin, gas-pressure-supported disks enveloped by magnetized coronae. These disks remain remarkably stable even under intense radiation, showing no signs of thermal instability.

By contrast, double-loop configurations, which lack net vertical magnetic flux, form magnetically elevated disks, where magnetic pressure dominates throughout the structure. These flows tend to lack strong jets, show greater variability in emitted radiation, and feature denser equatorial outflows. “The disk is supported primarily by both magnetic and radiation pressure throughout, with the former dominating,” the study notes.

This distinction has observational implications. According to the research, models with double-loop fields tend to show stronger variability and lower radiative efficiency. This may help interpret the behavior of X-ray binaries in different accretion states, or why some ULXs appear radio-quiet even at high luminosities.

Black Hole Engines, Simulated at Exascale

Behind these results is a massive technical achievement. The team ran their models using AthenaK, a new version of Athena++ adapted for exascale systems. The simulations were executed on Frontier and Aurora, two of the most powerful supercomputers on Earth, capable of performing quintillions of calculations per second.

The code includes a fully coupled relativistic radiation transport algorithm, solving time-dependent transfer equations without any M1 or fluid-like approximations. Christopher White of Princeton University led the development of this algorithm, while Patrick Mullen, Member (2021-22) in the School of Natural Sciences and now at Los Alamos National Laboratory, integrated it into the radiation GRMHD framework.

According to the paper, “Ours is the only algorithm that exists at the moment that provides a solution by treating radiation as it really is in general relativity.” These models required up to 120,000 node hours per run and resolved structures as thin as H/r ≈ 0.02, an unprecedented scale for global black hole accretion models.

Even subtle effects like radiation drag on the jet spine and outflow beaming factors were accurately captured. Jet Lorentz factors reached up to 10.2 in the fastest cases, and photon escape was found to be highly angle-dependent, with implications for observed brightness in systems like little red dots detected by JWST.