This theory challenges long-standing ideas of conflict-driven extinction and places gene flow at the center of the Neanderthal story. As more fossil and genetic data accumulate, the idea that Neanderthals were eradicated by superior tools or strategy is giving way to a more nuanced explanation. Blending rather than battling, the two species may have shared space, culture, and eventually, genes.

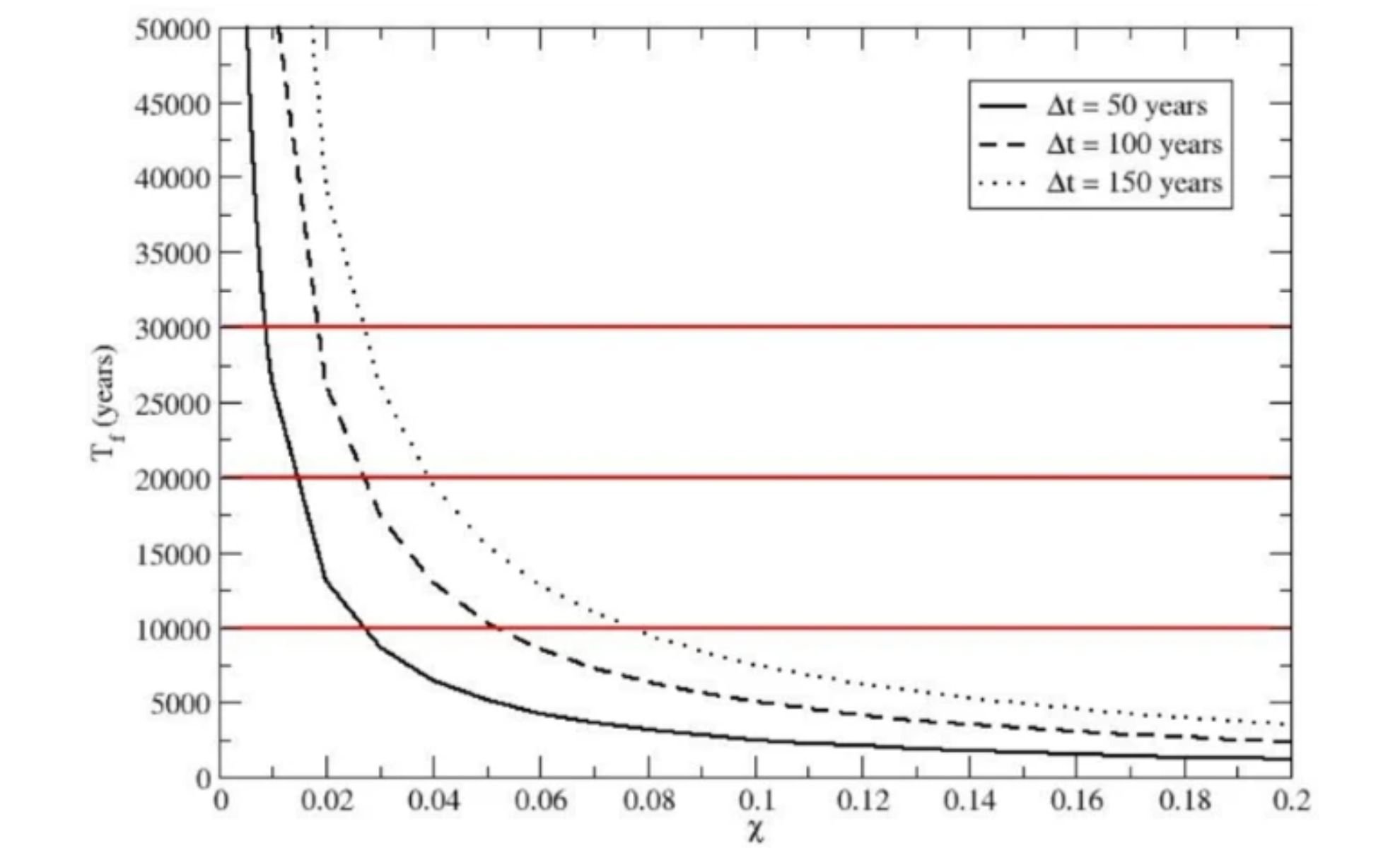

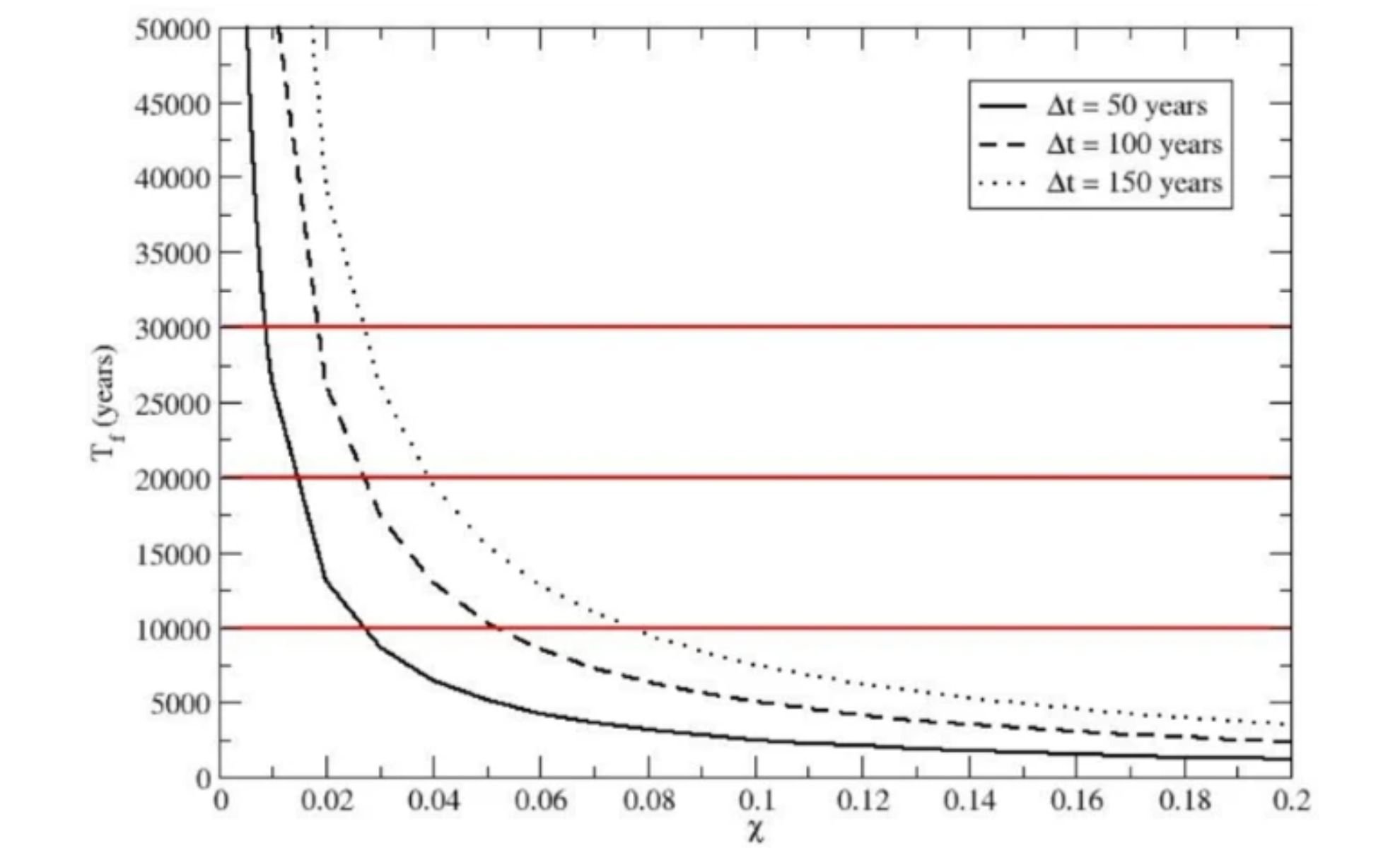

The new findings add weight to the hypothesis that recurrent, small-scale migrations of Homo sapiens into Neanderthal territory slowly replaced their genetic identity. According to research published in Scientific Reports, this process could have erased the Neanderthal genome in as little as 10,000 to 30,000 years, a time frame consistent with archaeological evidence of coexistence.

A Disappearance without Violence or Catastrophe

The mystery of Neanderthal extinction has long puzzled scientists, especially given their resilience to Europe’s harsh environments. Previous theories pointed to climatic shocks, resource competition, or disease, but recent analysis questions whether these factors alone can account for the loss of a species so deeply embedded in the landscape.

Notably, there is no archaeological evidence of direct conflict between the two species. As noted by archaeologist Ludovic Slimak, the contact period appears to have involved peaceful coexistence and even cultural exchanges. Artifacts and cave art suggest some degree of interaction, perhaps even influence, between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

In the same period, genetic traces of Neanderthal DNA began appearing in the Sapiens genome. This is one of the strongest signals that hybridization was not just possible but common. According to the study, these repeated gene flow events may have gradually shifted the genetic identity of Neanderthal populations until they were no longer distinct.

Mathematical Modeling of Genetic Dilution

Researchers built a neutral species drift model to explore this possibility, simulating how Neanderthal genes could be diluted over time without any selection pressure. Their model assumes that small Neanderthal groups received periodic inflows of Sapiens genes from a much larger population reservoir.

The results show that even modest immigration fractions, on the order of a few individuals per cycle, would be sufficient to alter the genetic makeup of Neanderthal populations over millennia. “Sustained gene flow from a demographically larger species could account for Neanderthals’ genetic absorption,” the authors explain.

According to the study, this would happen without needing major environmental or demographic disruptions. Over successive generations, the Neanderthal alleles would be statistically replaced until only traces remained, much like what we observe in modern human DNA today, which carries about 1 to 2 percent Neanderthal ancestry in non-African populations.

Not Extinction, but Absorption

Far from being wiped out, Neanderthals may have simply been genetically merged into the Homo sapiens population. The study describes a process where the last Neanderthal groups slowly lost their distinctiveness through continuous admixture, resulting in a species that disappeared not through extermination, but assimilation.

Importantly, the model emphasizes the structure of Neanderthal populations, which likely consisted of small, scattered tribes. This made them especially vulnerable to demographic influence from larger, incoming Sapiens groups. Over time, repeated contacts, even if sporadic, could reshape the entire gene pool.

According to the authors, “small-scale genetic immigration events could be relevant to explain the observed patterns of Neanderthal ancestry.” They also note that this approach offers a conservative baseline: if gene flow alone is enough to explain Neanderthal disappearance, then any additional factors, like selection or competition, would only accelerate the process.