The Constituent Assembly, which adopted the Constitution on November 26, 1949, after deliberations that lasted three years, began its journey with the passage of the Objectives Resolution drafted by Jawaharlal Nehru that became the foundation of the Preamble to the Constitution.

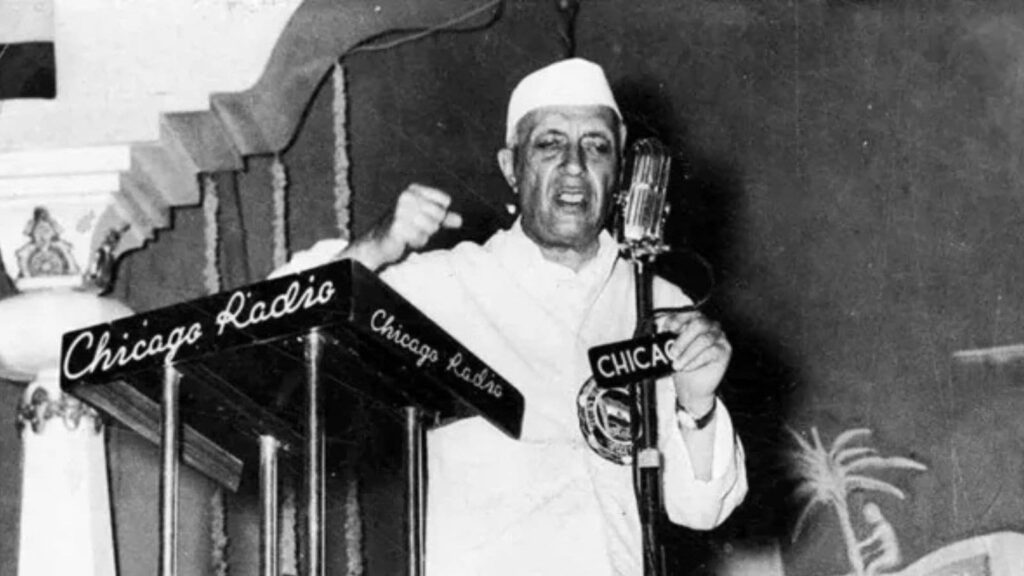

Nehru presented the Objectives Resolution on December 13, 1946, and it was adopted by the Assembly on January 22, 1947. In the course of two long speeches — one while presenting the Resolution and the other, when he requested the Assembly to pass it — Nehru swung from explanations of some of his choices to reveries on how he found himself weighed down by the huge task at hand.

Why Socialism is absent

A socialist in his beliefs, Nehru said he had avoided adding socialism to the Resolution, as it could create disagreements. “The main thing is that in such a Resolution, if, in accordance with my own desire, I had put in, that we want a Socialist State, we would have put in something which may be agreeable to many and may not be agreeable to some, and we wanted this Resolution not to be controversial in regard to such matters,” Nehru said. “Therefore, we have laid down, not theoretical words and formulae, but rather the content of the thing we desire. This is important and I take it there can be no dispute about it.”

The Congress leader also explained why he did not insert the word democratic in his draft (it eventually came up in the Preamble). He said India had always stood for democratic institutions and that democracies of the world may have to “change their shape somewhat before long if they have to remain completely democratic”.

“We are not going just to copy, I hope, a certain democratic procedure or an institution of a so-called democratic country. We may improve upon it. In any event whatever system of Government we may establish here must fit in with the temper of our people and be acceptable to them. We stand for democracy. It will be for this House to determine what shape to give to that democracy, the fullest democracy, I hope,” Nehru said.

“The House will notice that in this Resolution, although we have not used the word ‘democratic’ because we thought it is obvious that the word ‘republic’ contains that word and we did not want to use unnecessary words and redundant words, we have done something more than using the word. We have given the content of democracy in this Resolution and not only the content of democracy but the content… of economic democracy in this Resolution.”

A caution

In his comments before the passage of the Resolution, Nehru cautioned that the Assembly should not presume to decide what was good for future generations. “It may be that the Constitution this House may frame may not satisfy … free India. This House cannot bind down the next generation, or the people who will duly succeed us in this task. Therefore, let us not trouble ourselves too much about the petty details of what we do; those details will not survive for long, if they are achieved in conflict. What we achieve in unanimity, what we achieve by co-operation, is likely to survive. What we gain here and there by conflict and by overbearing manners and by threats will not survive long. It will only leave a trail of bad blood.”

Nehru said he hoped for the Assembly to create a good Constitution but cautioned that a free India may not “be bound down by anything that even this House might lay down for it”. “A free India will see the bursting forth of the energy of a mighty nation. What it will do and what it will not, I do not know, that it will not consent to be bound down by anything. I should like the House to consider that we are on the eve of revolutionary changes, revolutionary in every sense of the word, because when the spirit of a nation breaks its bonds, it functions in peculiar ways and it should function in strange ways,” he said.

The weight of history

Nehru said the country stood between two eras and that this was much more than a Resolution. “It is a Declaration. It is a firm resolve. It is a pledge and an undertaking and it is for all of us, I hope, a dedication.”

Requesting the Assembly to consider the Resolution as a spirit rather than just legal wording, the future PM said, “Words are magic things often enough, but even the magic of words sometimes cannot convey the magic of the human spirit and of a nation’s passion. And so, I cannot say that this Resolution at all conveys the passion that lies in the hearts and the minds of the Indian people today. It seeks very feebly to tell the world of what we have thought or dreamt of for so long, and what we now hope to achieve in the near future.”

Nehru said he was feeling the weight of history. “My mind goes back to the great past of India to the 5,000 years of India’s history, from the very dawn of that history that might be considered almost the dawn of human history, till today. All that past crowds around me and exhilarates me and, at the same time, somewhat oppresses me. Am I worthy of that past? When I think also of the future, the greater future I hope, standing on this sword’s edge of the present between this mighty past and the mightier future, I tremble a little and feel overwhelmed by this mighty task.”

Yet, Nehru saw “some magic in this moment of transition from the old to the new”.

“I feel also that in this long succession of thousands of years, I see the mighty figures that have come and gone and I see also the long succession of our comrades who have laboured for the freedom of India. And now we stand on the verge of this passing age, trying, labouring, to usher in the new. I am sure the House will feel the solemnity of this moment and will endeavour to treat this Resolution which it is my proud privilege to place before it in that solemn manner,” he said.