In a remote cave in southern Italy, sealed off for over 130,000 years, scientists have uncovered evidence that could upend long-standing beliefs about how Neanderthals adapted to Ice Age Europe. For decades, researchers argued these extinct humans evolved large, broad noses as a physiological response to frigid, dry climates. A new study challenges that claim at its anatomical core.

The discovery centers on Altamura Man, a remarkably preserved Neanderthal skeleton embedded in calcite deep inside Lamalunga Cave. The thick mineral crust protected the fossil’s delicate features, including internal nasal structures never before found intact in any other Neanderthal skull.

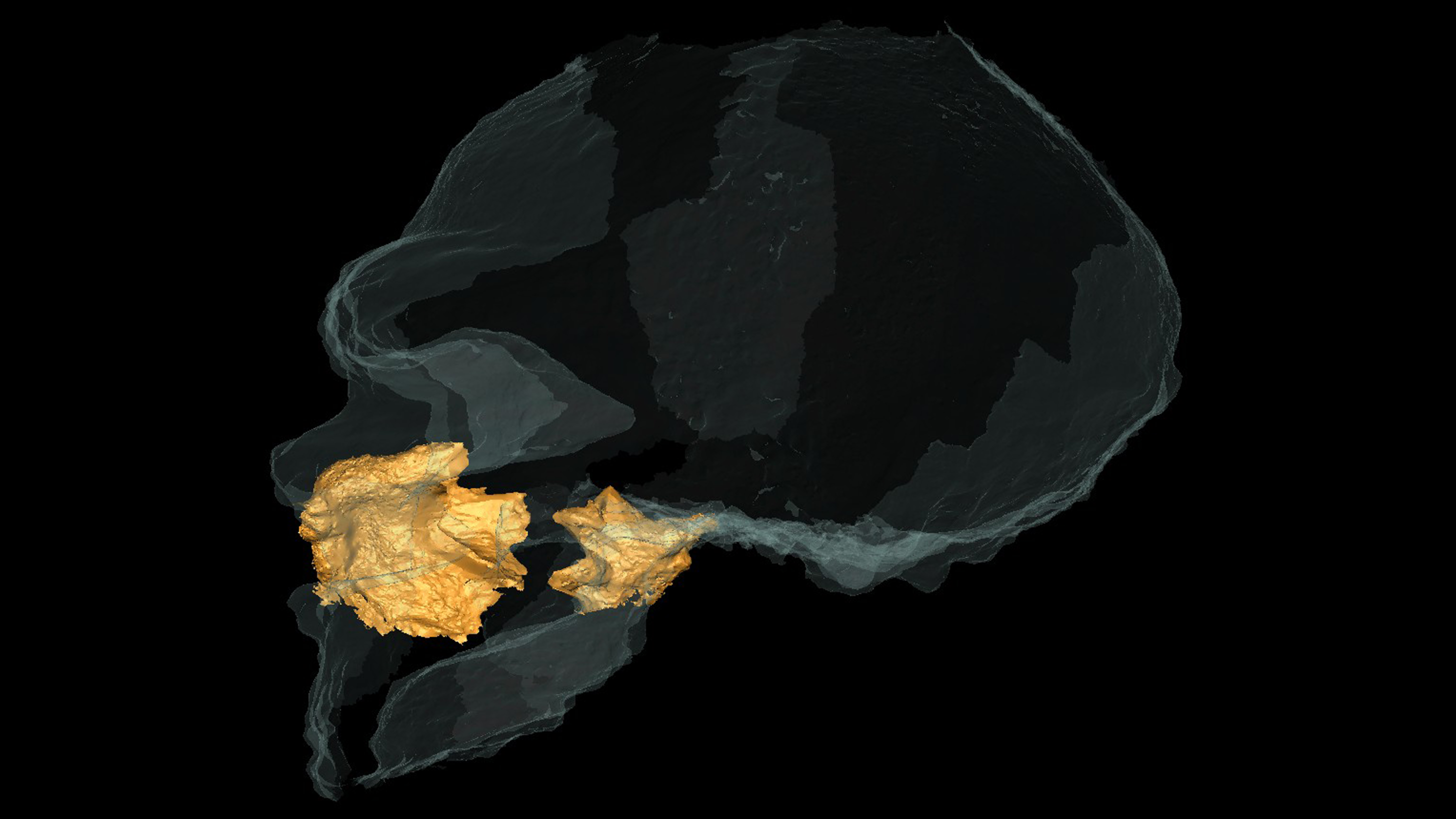

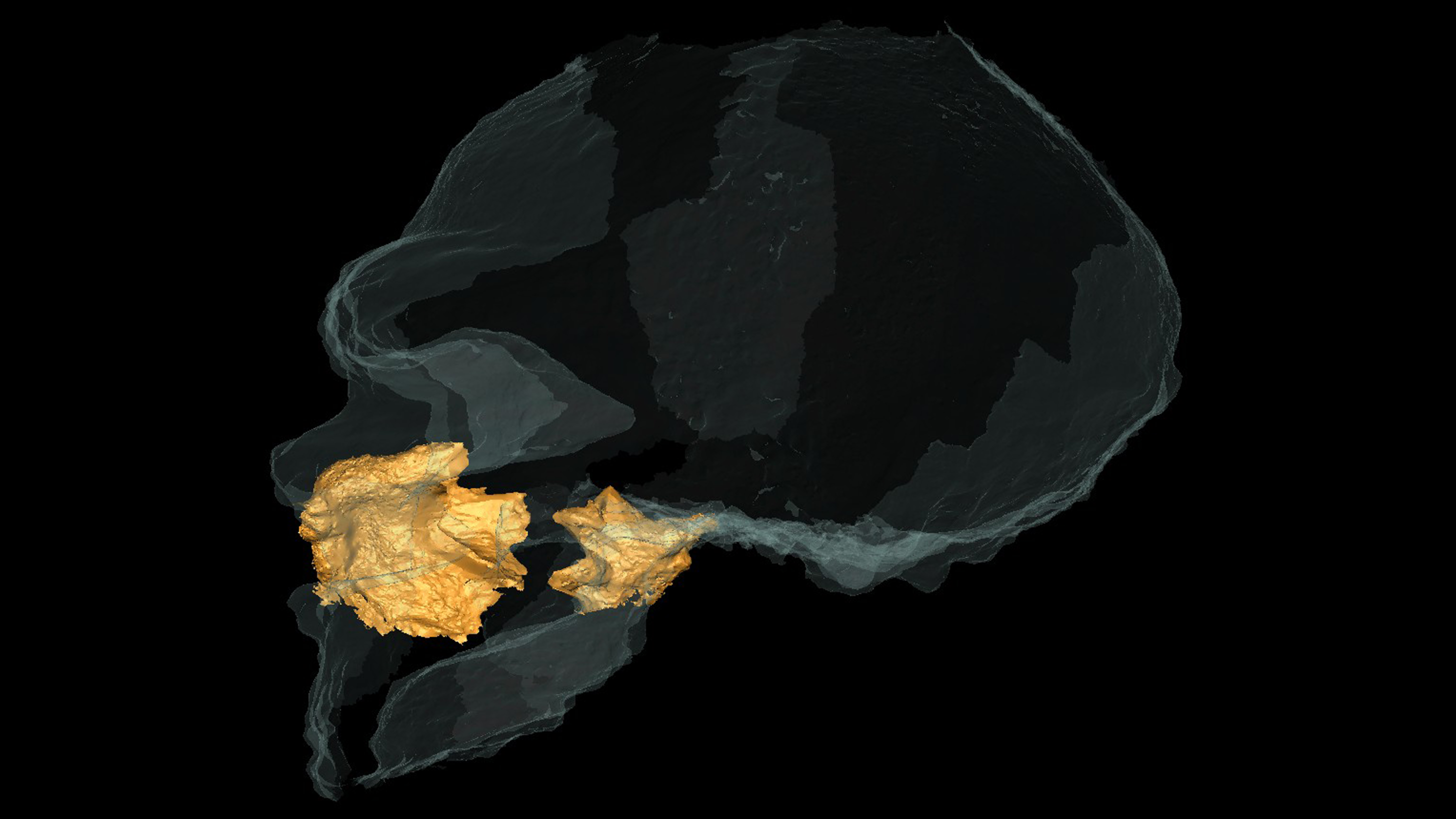

Using fiber-optic imaging and 3D digital modeling, a team of paleoanthropologists has now reconstructed the inner nasal cavity of Altamura Man without removing the skull from the cave. Their findings suggest that previously assumed cold-adaptive traits in the Neanderthal nose were not present — and may never have existed across the species.

Fossil Preserved in Stone Yields Unprecedented Nasal Data

When cave explorers found Altamura Man in 1993, the fossil was nearly complete — a rare occurrence in paleoanthropology. But its exceptional preservation came at a cost: extracting it risked damage. For decades, scientists left the remains in situ, encased in calcite. That caution paid off.

Led by Costantino Buzi of the University of Perugia, researchers deployed endoscopic probes to capture video from inside the skull’s nasal cavity. Using those visuals, they created detailed 3D models of internal nasal bones, including the ethmoid, vomer, and inferior nasal conchae — structures that had been missing or damaged in every other known Neanderthal skull.

“The general shape of the nasal cavity and nasal aperture in Neanderthals follows a quite constant trend,” Buzi told Live Science. “In general, it starts large but gets larger during their evolution, with very large nasal openings in the last populations of the species.”

Yet what the team didn’t find was even more significant: two of the three traits once considered unique to Neanderthals — including a vertically oriented nasal projection and a specific bony swelling — were absent in Altamura Man. That casts doubt on their classification as species-defining features.

“Two of the three previously proposed unique features of the Neanderthal nasal cavity do not appear to be present in this specimen,” said Todd Rae, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Sussex who reviewed the findings but was not involved in the study. “The lack of unique traits shows that there is variation in the species that was not previously known.”

Challenging the Cold-Weather Hypothesis

The long-standing theory that Neanderthal nasal structure evolved to humidify and warm cold air has now been thrown into question. These assumptions rested largely on reconstructions and comparative models—not direct fossil evidence. Until now.

According to the PNAS paper, the midfacial anatomy of Neanderthals was likely shaped by several overlapping pressures rather than a single climatic adaptation. The absence of internal nasal “autapomorphies” — or species-specific traits — suggests previous interpretations may have overemphasized cold adaptation based on incomplete fossils.

Instead, researchers argue the nasal cavity could reflect functional needs tied to body size and physiology. Neanderthals had massive, muscular builds, which may have required greater oxygen intake. A wide nasal passage could serve as a mechanical solution to increased respiratory demand — not necessarily a shield against icy air.

“The characteristic midfacial morphology of H. neanderthalensis… is the result of a combination of factors and not a direct result of respiratory adaptations,” the authors write in the PNAS paper.

Virtual Paleoanthropology Redefines Fossil Science

The findings are not just significant for what they reveal, but for how they were obtained. The research relied entirely on non-invasive digital reconstruction, marking a shift in how sensitive fossils can be studied without risking damage.

Buzi and his team are part of the THOR Project, which specializes in high-resolution imaging techniques in karstic cave environments. By using virtual paleoanthropology — a growing subdiscipline that merges archaeology, 3D modeling, and digital forensics — they’ve preserved a uniquely valuable fossil while extracting new evolutionary insight.

The research also builds on prior digital modeling of Altamura Man, including earlier anatomical studies such as the one published in Communications Biology in 2023 and detailed in this 2024 Quaternary Science Review.

These technologies are now setting a new standard for paleoanthropological methods — especially when fossil preservation, ethical concerns, or legal limitations prevent physical extraction.

Evolutionary Models Face a Reset

The findings don’t just revise Neanderthal biology — they pressure-test how researchers define “adaptation” in the first place. For decades, evolutionary narratives have leaned heavily on assumed form-function relationships: broad noses must warm air; stocky bodies must conserve heat.

But Altamura Man shows that even iconic anatomical traits may not always be what they seem. Without the internal features once linked to respiratory efficiency, the Neanderthal nose may be better explained as a product of energetic and metabolic demand, not environmental selection.

This single fossil, locked away for millennia, has cracked open one of paleoanthropology’s most persistent myths. And as virtual methods allow researchers to reexamine old specimens in new ways, more long-held assumptions could follow.