In the world of art and anatomy, few images are more recognizable—or more dissected—than Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Drawn in 1490, the iconic sketch has come to symbolize the Renaissance ideal of harmony between man, nature, and geometry. But for all its acclaim, one enduring question has remained unresolved: what geometric system underpins the figure’s precise proportions?

A newly published peer-reviewed study may have found the answer, and it’s not what generations of scholars have assumed. Forget the golden ratio, the aesthetic constant often linked to beauty and balance in art and nature. Instead, the key to da Vinci’s vision might lie in a far more obscure—but structurally profound—principle of geometry that wasn’t formally defined until the 20th century.

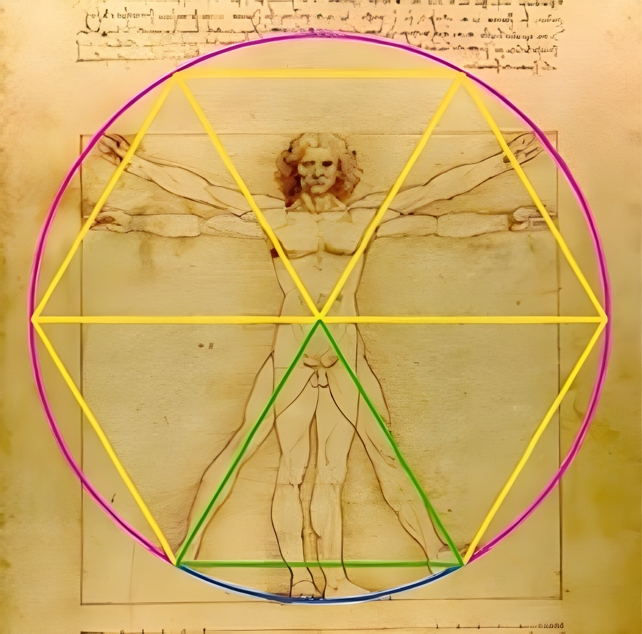

That principle appears to be tetrahedral symmetry—a form of optimal spatial organization more commonly used in molecular chemistry, crystallography, and structural physics than in Renaissance sketchbooks. And the evidence for it may lie, quite literally, in the triangle formed at the intersection of the Vitruvian Man’s outstretched legs.

Published in the Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, the new analysis proposes that da Vinci embedded this advanced geometry into his famous drawing, centuries before the concept was mathematically formalized.

The Triangle That Reshapes the Man

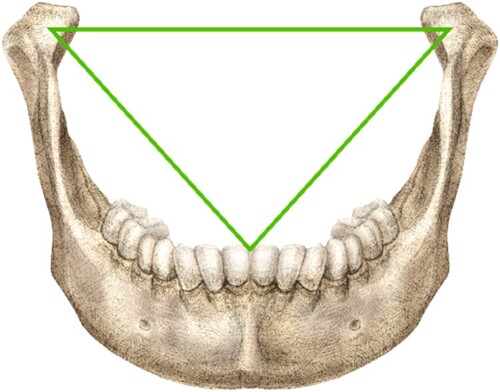

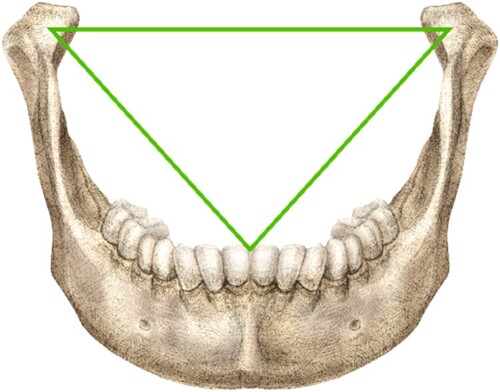

According to Dr. Rory Mac Sweeney, a London-based dentist and the paper’s lead author, the breakthrough came from revisiting da Vinci’s own writings. In his annotations to the Vitruvian Man, da Vinci wrote, “If you open your legs… and raise your hands enough that your extended fingers touch the line of the top of your head… the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle.”

Mac Sweeney took this literally. He plotted an equilateral triangle between the figure’s feet and navel and found that its height-to-base ratio hovered between 1.64 and 1.65—remarkably close to the tetrahedral ratio of 1.633, first mathematically described in 1917.

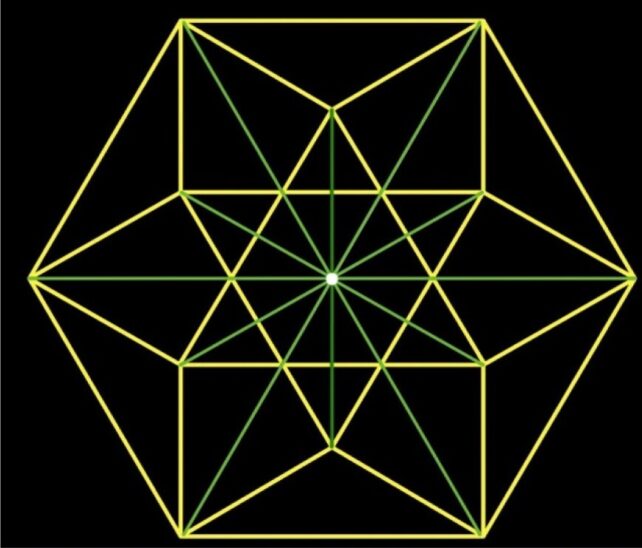

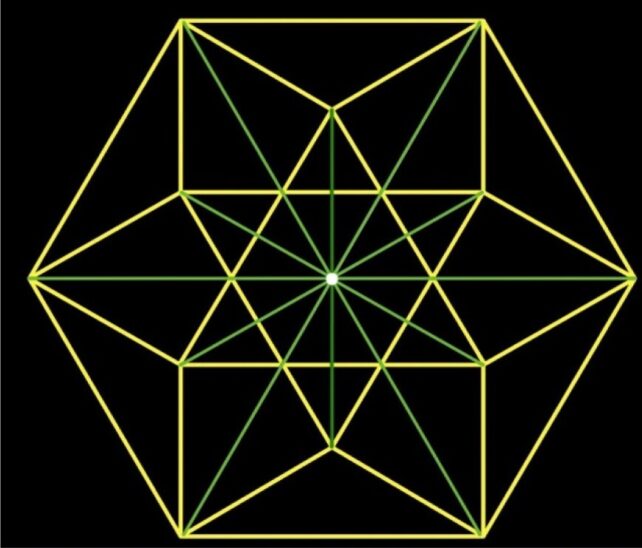

This ratio reflects the ideal vertical relationship between the base and apex of four closely packed spheres forming a pyramid—a tetrahedron—one of the most structurally efficient forms found in nature.

That precise ratio doesn’t align with the golden ratio, long theorized to have influenced the Vitruvian Man, which is roughly 1.618. While beautiful in its own right, the golden ratio doesn’t quite match the Vitruvian figure’s spatial layout as cleanly as this triangular geometry does.

How the Jaw—And Geometry—Connect

Mac Sweeney’s interest in anatomical triangles wasn’t abstract—it came from his work in dentistry. He noticed striking parallels between the proportions in the Vitruvian Man and a longstanding clinical standard: the Bonwill Triangle. First defined by dentist G. Bonwill in 1864, this triangle maps optimal jaw alignment using three specific points of dental contact, and crucially, it too is based on a 1.633 ratio.

“I wasn’t looking for anything esoteric,” Mac Sweeney explained in the study. “I just started to see the same geometry repeating in two very different parts of the human body.” The connection, he argues, hints at an underlying spatial logic not only in dental mechanics but throughout the entire body.

His hypothesis aligns with how tetrahedral structures appear in physics and biology. They’re seen in the arrangement of water molecules, the latticework of crystals, and even viral capsids. These structures minimize energy, maximize space, and form the backbone of some of nature’s most efficient systems.

If human anatomy mirrors this packing logic—repeating tetrahedral geometry from jaw to torso—it could explain why da Vinci gravitated toward it intuitively, even without formal mathematical tools.

New Math From Old Masters

Skeptics may argue that the triangle’s presence is a coincidence or a case of retroactive interpretation. After all, da Vinci was heavily influenced by the Roman architect Vitruvius, whose ideas about symmetry, proportion, and architecture inspired the drawing’s dual-square and circle framing.

But da Vinci’s own notes contradict a purely Vitruvian reading. His emphasis on leg spacing and the equilateral triangle suggests that he may have perceived geometry not as abstraction but as anatomical truth. And Mac Sweeney’s calculations support that reading. His overlaid triangle not only aligns with da Vinci’s anatomical positioning but also intersects the navel—the anatomical center da Vinci repeatedly highlighted as a reference point.

That specific ratio has never before been associated with the Vitruvian Man in published research. And unlike past theories, such as misapplied golden section overlays or symbolic interpretations, the tetrahedral model is mathematically testable and anatomically consistent.

Symmetry, Structure, and the Cosmos

At its core, this new perspective offers a startling possibility: that Leonardo da Vinci may have visualized a universal organizing principle long before it had a name. The idea that the body—like crystals or molecules—follows spatial laws of maximum efficiency links Renaissance anatomy to cutting-edge science in a way few anticipated.

The implications are far-reaching. If such geometric relationships are consistent across different biological systems, it raises new questions about how we design prosthetics, analyze motion, or even simulate organic growth in artificial intelligence models.

At the very least, it repositions the Vitruvian Man as more than a symbol of artistic genius. It becomes a data-rich, visually encoded statement about the structure of life itself—a kind of human blueprint drawn in ink, but grounded in universal constants.

And it all may hinge on a triangle we’ve been overlooking for half a millennium.