For decades, a faint groove etched into ancient human teeth was held up as a milestone of early culture. It was the alleged evidence that Homo erectus and Neanderthals were already probing their gums with sharpened sticks—practicing a crude form of dental hygiene long before toothbrushes. But new research, drawing from over 500 fossil and modern primate specimens, now casts serious doubt on that assumption.

A peer-reviewed study published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology suggests these so-called toothpick grooves may not reflect intentional behavior at all. In fact, similar marks appear in the mouths of wild primates who have never been seen using tools. In some cases, the grooves are virtually identical to those once interpreted as signs of cultural sophistication.

This revelation doesn’t just correct a detail—it reopens a broader question: How much of what scientists interpret as ancient behavior is actually just biology? The line separating intentional tool use from incidental wear is thinner than it once seemed.

Grooves Without Intention

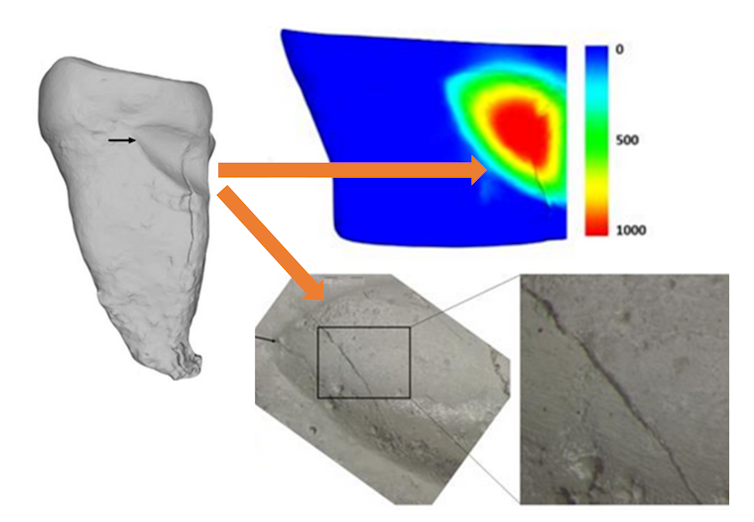

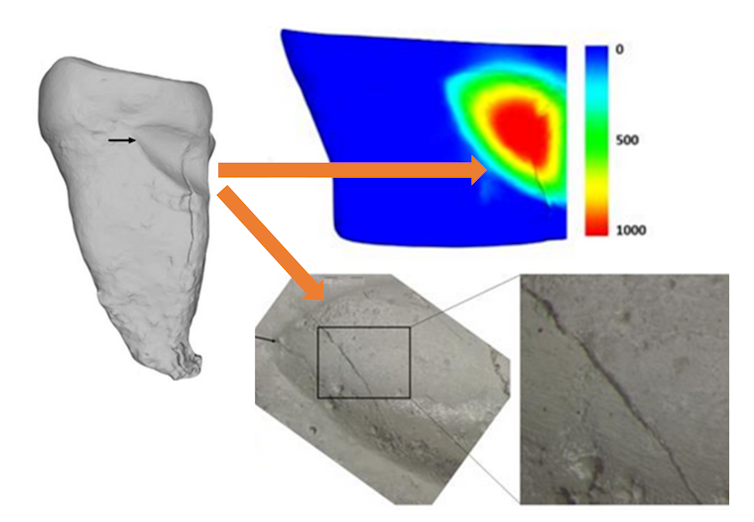

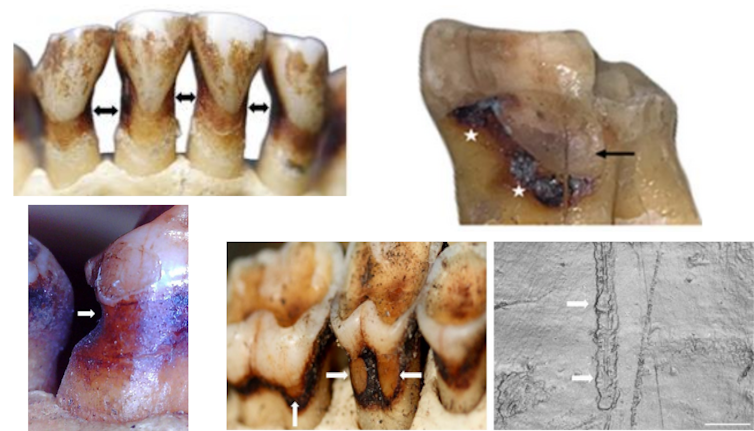

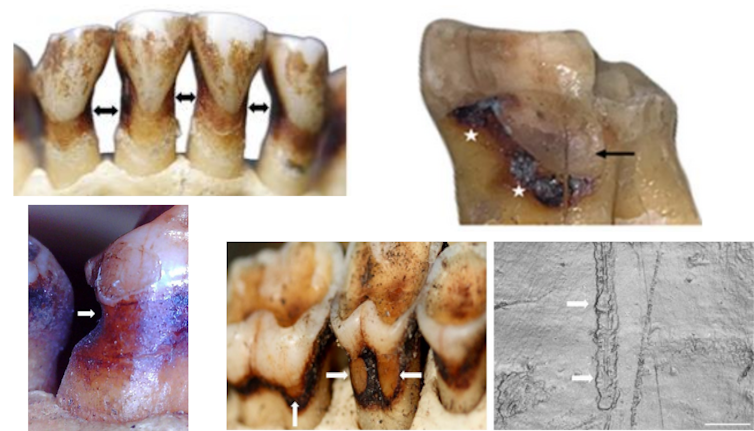

Led by researchers Ian Towle and Luca Fiorenza from Kyoto University and Griffith University, the team analyzed more than 500 teeth across 27 species of wild primates, including orangutans, macaques, and fossil apes. Their methodology combined confocal laser scanning and 3D microscopy to examine non-carious cervical lesions—grooves or tissue loss not caused by decay.

Roughly 4% of individuals showed root grooves remarkably similar in shape and location to those found in fossilized humans. Some displayed parallel micro-scratches, tapering walls, and smooth surfaces—features previously attributed to the repeated insertion of sticks or plant fibers between teeth.

But none of the primates studied had ever been observed using their own dental tools, nor do they live in environments where anthropogenic interference is likely. This rules out cultural behavior and suggests that natural biomechanical forces, such as chewing tough foods or contact with abrasive particles, can mimic what had long been mistaken for early dental care.

“They’re almost identical to what’s been interpreted as cultural in humans,” Towle said. “Tooth grooves alone,” Fiorenza added, “are not enough to infer complex behavior.”

This argument is further expanded in a widely circulated explainer from The Conversation, co-authored by Fiorenza.

What Apes Don’t Get—Modern Humans Do

Beyond groove formation, the researchers noted something even more telling: the complete absence of abfraction lesions in non-human primates. These are deep, V-shaped notches near the gumline, commonly seen in humans today. Abfractions are linked to habits like tooth grinding, forceful brushing, and acidic diets—all hallmarks of industrialized societies.

Despite examining species with powerful bite forces and abrasive diets—conditions seemingly perfect for developing such lesions—not a single abfraction was found in the sample. This stark contrast points to abfraction as a modern, human-specific phenomenon rooted in lifestyle rather than anatomy.

This mirrors trends seen in other dental pathologies. Impacted wisdom teeth, malocclusion, and chronic decay are now understood as largely post-agricultural developments, a consequence of softer diets, processed foods, and altered jaw growth in modern populations.

In their detailed breakdown on Phys.org, the authors argue that “even in something as everyday as toothache, our evolutionary history is written in our teeth, but shaped as much by modern habits as by ancient biology.”

A Call for Scientific Caution

The reevaluation of toothpick grooves exposes a larger vulnerability in paleoanthropology: the temptation to over-interpret ambiguous signs as cultural behaviors. Many fossil records lack the ecological or comparative context necessary to determine intention versus consequence.

For nearly a century, grooves between fossilized molars were cited as “the oldest human habit.” But the historical absence of comparative data from other primates now appears to have skewed those early interpretations. This study makes clear that such lesions can—and do—form naturally, without cultural intervention.

“Without a broader ecological and comparative framework, we risk seeing intention where there may be none,” Fiorenza warned in an interview with The Conversation.

Caution is now advised before declaring any fossilized pattern a product of intelligence, culture, or care. And that caution may extend to other areas of evolutionary science where isolated anatomical features are used to infer behavior or cognition.