A new study suggests that people residing in economically and environmentally burdened neighborhoods show measurable signs of dementia risk—even before symptoms appear. Researchers used brain scans and blood tests to uncover biological changes linked to Alzheimer’s and related diseases.

This research, led by Wake Forest University School of Medicine, points to a stark reality: social vulnerability, environmental inequality, and economic hardship don’t just shape daily life—they might shape the brain itself. It’s the first time such detailed links have been made between place-based social factors and biomarkers of dementia, providing concrete evidence of how deeply neighborhood conditions can affect long-term cognitive function.

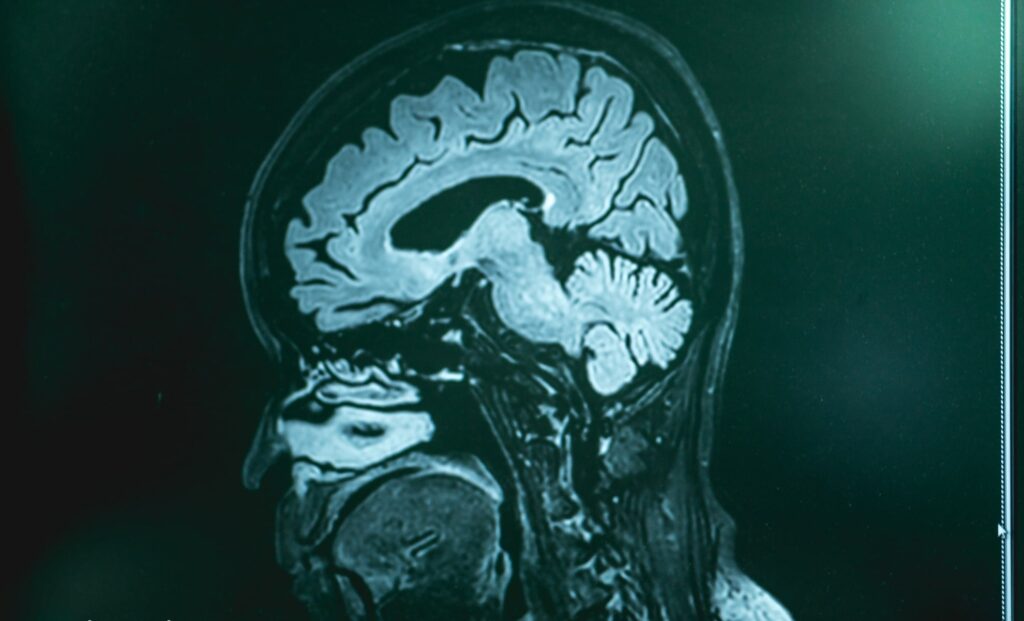

With data from 679 adults involved in the Healthy Brain Study at the Wake Forest Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, the scientists cross-referenced participants’ brain health with three national indicators: the Area Deprivation Index, the Social Vulnerability Index, and the Environmental Justice Index. The results indicate that where someone lives could leave lasting biological fingerprints on brain structure, especially in historically underserved communities.

Disparities in Brain Structure Tied to Neighborhood Stress

According to the study, residents from high-burden neighborhoods showed clear biological signs related to dementia. These included a thinner cerebral cortex, white matter abnormalities indicative of vascular disease, and reduced or uneven blood flow in the brain. All these features are strongly associated with cognitive decline and memory loss over time, reports ScienceDaily.

Lead author Sudarshan Krishnamurthy, a sixth-year M.D.-Ph.D. candidate, pointed out that the study is among the first to directly link social and environmental stressors to advanced markers of neurodegenerative disease. Timothy Hughes, senior author and associate professor at Wake Forest, added that the findings reinforce earlier work showing that neighborhood conditions can significantly influence brain function.

Disproportionate Impact on Black Communities

The study revealed that Black participants were more likely to show stronger correlations between neighborhood disadvantage and dementia-related brain changes. According to SciTechDaily, these communities often face elevated levels of environmental pollution, housing insecurity, and limited access to nutritious food and healthcare. These cumulative factors appear to deepen the physiological imprint of stress on the brain.

This racial disparity was most evident in the brain imaging results, which showed more pronounced reductions in blood flow and greater structural degradation in participants from high-vulnerability zip codes. As the authors note, this suggests a compounded effect where historical inequities intersect with biological risk.

A Call to Address Systemic Conditions

The researchers stress that individual lifestyle choices aren’t enough to mitigate these effects. According to Krishnamurthy, improving community infrastructure—such as clean air initiatives, equitable housing policies, and access to medical services—may be essential for protecting brain health at the population level.

The study, published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Behavior & Socioeconomics of Aging, calls for a shift in public health strategy. Instead of focusing solely on personal interventions, it highlights the need to address the broader systems and structures shaping health outcomes. This reflects a growing scientific consensus that the social determinants of health are not peripheral concerns but central to disease prevention.