If it was in Bihar that the early flames of resistance were lit against the Indira Gandhi government, in the form of the Jayaprakash Narayan Movement of 1974, eventually leading her to impose the Emergency and be voted out of power, it was from Bihar that the late Congress leader also began her climb back.

On Mrs Gandhi’s death anniversary on October 31, in the midst of a Bihar poll battle that seems equally intractable for the Congress, it was to this fightback that senior party leader Jairam Ramesh referred.

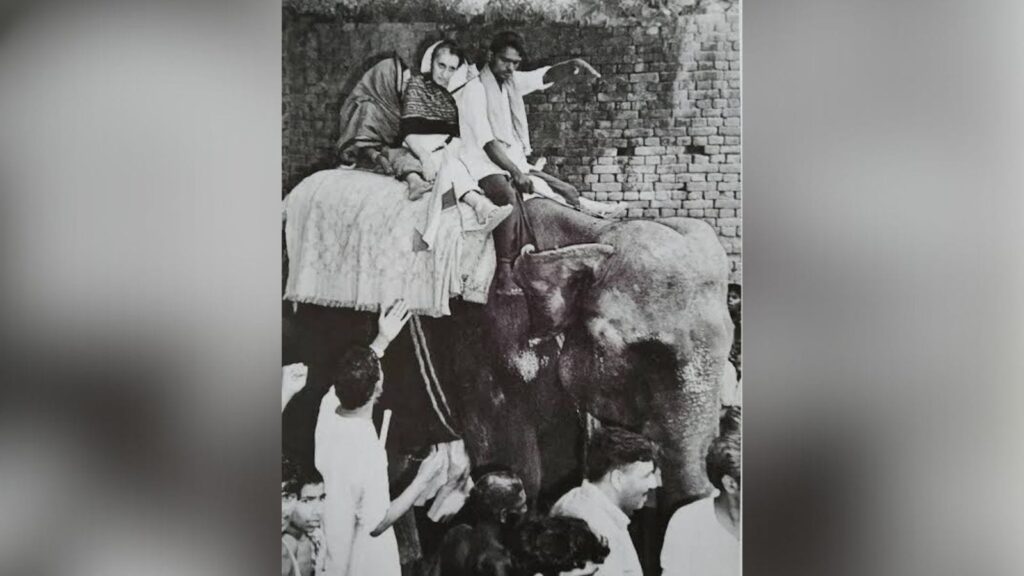

It was August 13, 1977, and the monsoon was in full swing. But keen to capture the mindspace of people months after the Congress’s post-Emergency Lok Sabha rout, Mrs Gandhi braved the elements – with a car, a jeep, a tractor, and finally an elephant – to reach the remote village of Belchi in Bihar, to meet families of Dalits killed in caste violence.

“This extraordinary and spontaneous outreach to families devastated by caste atrocities marked her political revival,” Ramesh wrote on X, sharing photos of Mrs Gandhi’s Belchi visit.

It had been over two months ago, on May 27, 1977, that the incident happened, with a group of Kurmis – the community to which JD(U) supremo Nitish Kumar belongs, and who are now OBCs in Bihar – accused of murdering eight Dalits and three members of the OBC Sonar caste.

A fight had broken out in Belchi the previous day. On May 27, a Kurmi group led by Mahavir Mahto attacked a Dalit named Singhwa with sticks and rods to avenge the fight. Singhwa’s father-in-law Janki Paswan ran to the Dalit settlement to get help. As 10-15 Dalit boys and men ran to Singwa’s rescue armed with sticks and rods, Mahavir’s men opened fire.

The Dalit youths were tied and taken to the fields, a pyre was lit and they were lined up before it, shot at, and pushed into the fire.

A watchman named Ganesh Paswan informed the police. Janki Paswan, who survived, also narrated the story to the police. But the Bihar Police dubbed it a gang war.

When the Belchi massacre happened, Bihar was under President’s Rule. But days after, in June 1977, the Janata Party came to power in the state, and Karpoori Thakur, who belonged to the Nai (barber) community, became the Chief Minister. While Thakur would earn the title of ‘Jannayak’ for his government’s reforms and measures for the downtrodden, his government too did not pay the Belchi case enough attention.

It was in Parliament that the massacre resonated more. When then Union Home Minister Chaudhary Charan Singh called the killings the result of a gang war, based on a report of the state government, the Opposition led by the Congress protested. A parliamentary fact-finding committee was sent to the village.

A member of this delegation was a young Ram Vilas Paswan, then one of the Janata Party’s rising Dalit stars. On July 13, 1977, Ram Vilas Paswan brought bones of those burnt alive to Parliament, seeking to place them on the table of the House, wrote Amit Kumar, former head of the Sanskrit department at Patna College, in an obit of the leader who later founded the Lok Janshakti Party.

Kumar wrote that Paswan, whom he knew well, told the House that the massacre was not a gang war, but a “Dalit versus Savarna war”.

Charan Singh was forced to revise his statement, and told the Rajya Sabha: “There might be certain economic reasons in the occurrence of such incidents, but the social malady of casteism with which our society was affected was the main reason behind such cases of atrocities and injustice.”

Mrs Gandhi, who had herself been defeated in the Lok Sabha elections earlier that year in which the Congress was voted out of power, saw in the case an opportunity to redeem herself and her party.

In her biography of Mrs Gandhi titled Indira: India’s Most Powerful Prime Minister, journalist-turned-politican Sagarika Ghose recalls journalist Janardan Thakur’s account of her visit: “When the jeep got stuck, a tractor was pressed into service but even that got stuck… Smt Gandhi was walking through the mud… Some Congressmen refused to go saying there was waist-deep water ahead, but Smt Gandhi was still marching on, her sari raised above her ankle. ‘Of course I can wade through water,’ she snapped at her frightened companions. A thoughtful local suggested an elephant. ‘But how will you climb an elephant?’ aides asked. ‘Of course I will,’ she said impatiently. ‘This is not the first time I have ridden an elephant. Bahut dino baad haathi pe charh rahi hun (It’s been some time since I rode an elephant)’.”

Ghose adds, “As Moti the tusker heaved up with Indira Gandhi on its back and a terrified companion, Pratibha, clinging to her, an accompanying cameraman cried out in delight, ‘Long live Indira Gandhi’. She smiled back at him.”

From where she got off the jeep, it took Mrs Gandhi three-and-a-half hours to reach Belchi. The sight of the former Prime Minister approaching on an elephant stunned the grieving families.

The gritty journey, and its photographs with the indelible image of her on an elephant, resurrected Brand Indira Gandhi. A year later, in November 1978, she was back in Parliament, defeating Veerendra Patil of the Janata Party in a by-election for the Chikmagalur seat in Karnataka by 70,000 votes.

The campaign slogan of the Congress in the election was: ‘Ek sherni sau langur (One lioness for 100 langurs), Chikmagalur bhai, Chikmagalur’.

By 1980, the Janata Party had splintered, and Mrs Gandhi returned as PM leading the Congress to a win in the Lok Sabha elections. In Bihar too, the Congress returned to power, winning 169 out of then 324 seats in 1980.

The Belchi trial picked up pace as soon as Mrs Gandhi became PM, though the chargesheet had already been filed when Karpoori Thakur was CM. Mahavir Mahto and Parshuram Dhanuk – the Dhanuks are also backward castes in Bihar – were sentenced to death by a trial court in 1980, by the Patna High Court in 1982, and the Supreme Court in 1983.

In November 1983, Mahato and Dhanuk were executed. This was one of the rare cases when caste violence led to the execution of the convicts.