After more than 20 years of painstaking restoration, Egypt has reopened one of the largest and most richly decorated tombs in the Valley of the Kings — that of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, a ruler whose reign marked the height of Egypt’s imperial and artistic power.

The tomb, known as WV22, lies in the arid hills on the western bank of the Nile, directly opposite modern-day Luxor. It was officially unveiled this weekend by Egypt’s Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, Sherif Fathy, marking a milestone in one of the most ambitious conservation efforts in the region’s recent history.

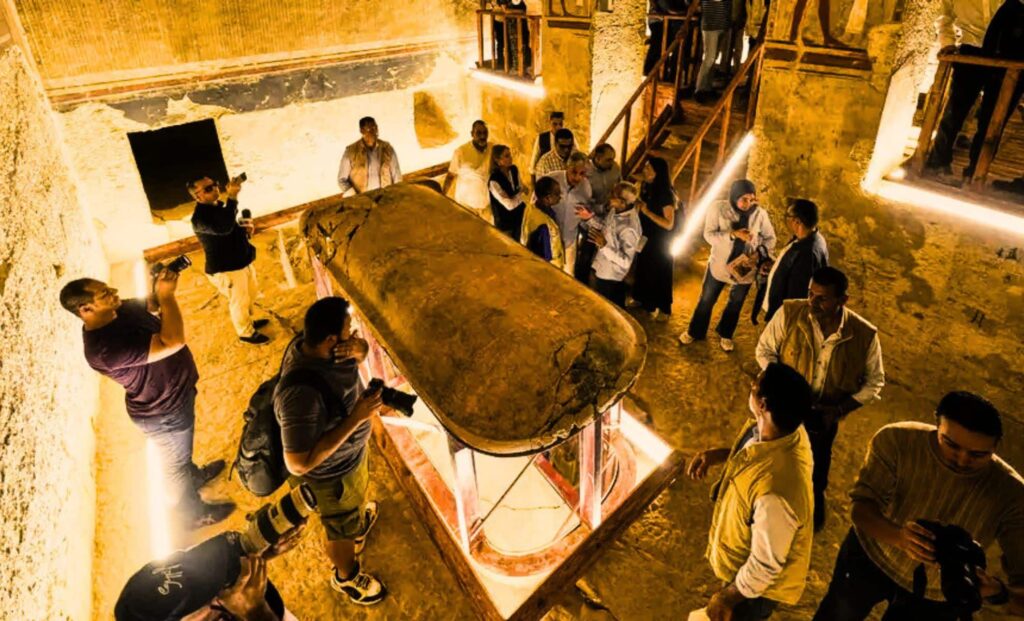

Originally discovered in 1799, the tomb had long suffered from natural degradation, structural collapse, and looting. Its contents, including the king’s sarcophagus, were removed centuries ago. What remains, however, are wall paintings described as “among the most exquisite” of the Eighteenth Dynasty — a period known for opulence, power and cultural sophistication, as documented by the Theban Mapping Project.

260 Specialists, Two Decades, Three Phases

The conservation effort was led by a Japanese-funded mission in collaboration with UNESCO and Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities. Over 260 archaeologists, conservators and technicians were involved in the three-phase project, which aimed not only to stabilize the tomb’s fragile interior but also to preserve its elaborate artwork.

“This was incredibly delicate work,” said Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. “The tomb had suffered from structural instability and moisture damage. In some places, pigments were literally falling off the wall.”

UNESCO regional director Nuria Sanz called the project a model of integrated conservation, conducted to the “highest level of international standards.” According to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the project also involved non-invasive imaging technologies to monitor deterioration over time.

Architecture and Artistry of a Golden Age

Amenhotep III, who reigned from 1390 to 1350 BCE, was the father of Akhenaten and grandfather of Tutankhamun. His reign marked a high point in ancient Egyptian architecture and diplomacy, with building campaigns that stretched from Nubia to Syria. The scale and detail of his tomb reflect both his global stature and the Egyptians’ complex beliefs in the afterlife.

The tomb features a 36-meter-long passage descending into a central burial chamber for the king, with two adjoining rooms likely designated for his Great Royal Wife Tiye and daughter Sitamun. The architectural layout, according to data from the Theban Mapping Project, represents an evolution in tomb design — more expansive and more symbolic of divine transformation.

The walls are covered with vibrant scenes from funerary texts, painted in pigments of ochre, black and ultramarine blue that have remarkably survived. Many murals depict Amenhotep engaging with gods like Osiris and Ra, symbolizing his eternal journey through the afterlife.

Why Egypt Is Spotlighting Ancient Tombs Now

The reopening comes amid a broader push to revitalize heritage tourism in Egypt, which accounts for nearly 12% of the country’s GDP. Alongside high-profile initiatives such as the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, authorities are spotlighting off-the-beaten-path archaeological treasures to diversify tourist interest and distribute foot traffic more sustainably.

Projects like the WV22 restoration support Egypt’s strategy to balance conservation with economic development. “We’re not just preserving the past,” said a UNESCO Cairo spokesperson. “We’re making it part of the present.”

By reopening Amenhotep III’s tomb — far less visited than the nearby Tomb of Tutankhamun — Egypt is offering travelers a more immersive experience of its ancient legacy while relieving pressure on better-known sites.