On December 18, 1947, Congress stalwart and then Union Home Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel said in Jaipur that he appreciated the enthusiasm of young men of the RSS, “but that it should be diverted to constructive channels”, and that a great deal needed to be done to make India militarily strong.

Three days later, Patel wrote to a Congress freedom fighter from Karnataka, Gangadhar Rao Deshpande, repeating the same message, while adding that one had to be careful while channelling the RSS’s energies positively, as “very few people are prepared to listen to reason”. This was in response to Deshpande’s letter to him stating that the RSS was a “well-knit and disciplined organisation”.

Addressing an event in Lucknow on January 6, 1948, Patel spoke up for the RSS again. “In the Congress, those who are in power feel that, by virtue of authority, they will be able to crush the RSS. You cannot crush an organisation by using the danda (stick). The danda is meant for thieves and dacoits. They (RSS leaders) are patriots who love their country. Only their trend of thought is diverted. They are to be won over by Congressmen with love,” Patel said.

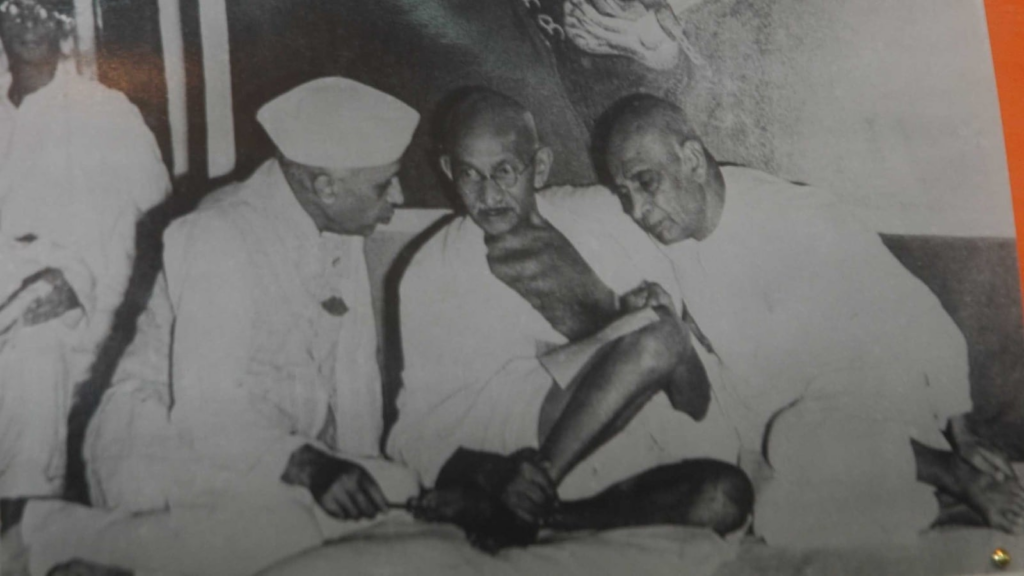

Another Congress stalwart and India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, however, did not share Patel’s view about the RSS. Nehru often used the term “anti-national” to describe the activities of the Sangh.

As the RSS marks 100 years of its establishment, its opinion when it comes to the two Congress leaders is still tinged by the events of those days — it respects Patel, but is uneasy and critical about Nehru.

Gandhi killing and the turning point

The positive views Patel held about the RSS notwithstanding, things changed drastically in the wake of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination on January 30, 1948, by Nathuram Godse, a former swayamsevak. Patel-led Union Home Ministry banned the Sangh in the wake of the killing.

On February 5, 1948, Patel informed Nehru that he had shot off telegrams to states to ban the RSS and had issued instructions to draft legislation to ban drilling and parading in semi-military uniforms to curb “private armies”.

He held that the Sangh was not involved in Gandhi’s assassination, but frowned upon the fact that it “distributed sweets” after the incident. He accused the RSS of spreading “communal poison”, even though he also suspected that a section of Muslims was not “loyal” to India.

On February 26, 1948, Nehru wrote back to Patel, saying Gandhi’s assassination was part of a much wider campaign organised by the RSS, and that many in the Delhi Police seemed to be sympathetic to the Sangh.

Patel disagreed with this, and the charge that the RSS was involved in the conspiracy to kill Gandhi. “The RSS was not involved at all. It was a fanatical wing of the Hindu Mahasabha directly under Savarkar that hatched the conspiracy…,” Patel wrote to Nehru, adding: “His (Gandhi’s) assassination was welcomed by those of the RSS and the Mahasabha, who were strongly opposed to his way of thinking… But beyond this, I do not think it is possible… to implicate any other members of the RSS or the Hindu Mahasabha. The RSS have other sins and crimes to answer for, but not this one.”

Still, Patel remained steadfast on his ban on the Sangh for months, going by the correspondence between him and then RSS chief M S Golwalkar.

In July 1948, Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who later founded the Jana Sangh – the BJP’s forerunner – wrote to Patel against the ban as well as raising the “disloyalty” of some Muslims. Patel responded by criticising the RSS. “The activities of the RSS constitute a clear threat to the existence of the government and the State,” he said. “As for Muslims,” he added, “I entirely agree with you as to the dangerous possibilities inherent in the presence in India of a section of disloyal elements.”

This was in line with what Patel had told Muslims at an event in Lucknow on January 6, 1948, accusing them of not condemning Pakistan’s attack on Kashmir following Partition. “You cannot ride two horses. Select one horse … Those who want to go to Pakistan can go there and live in peace,” he said.

In September 1948, Golwalkar wrote to Patel, offering that the Sangh would collaborate with the government to counter Communism if the ban on the RSS was lifted.

In his reply, Patel noted that “the RSS did service to the Hindu society”, but added: “The objectionable part arose when they (the RSS), burning with revenge, began attacking Mussalmans. All their speeches were full of communal poison… As a final result of that poison, the country had to suffer the sacrifice of Gandhi ji… RSS men expressed joy and distributed sweets after Gandhi ji’s death. It became inevitable for the government to take action against the RSS.”

Lifting of RSS ban

In 1949, speaking in Jaipur, Patel said: “We will not allow the RSS or any other communal organisation to throw the country back on the path of slavery or disintegration … I am a soldier, and in my time I have fought against formidable forces … If I feel that such a fight is necessary for the country’s good, I shall not hesitate to fight even my own son.”

Among the conditions imposed by Patel for lifting the ban on the RSS was that it show “explicit acceptance” of the national flag. Patel also wanted the Sangh to end its “secret” functioning and correct the fact that it did not have a written constitution.

In May 1949, Union Home Secretary H V R Iyengar wrote to Golwalkar, stating, “An explicit acceptance of the National Flag (with the Bhagwa Dhwaj as the organisational flag of the Sangh) would be necessary for satisfying the country that there are no reservations in regard to allegiance to the State.”

On July 11, 1949, the Centre finally lifted the ban on the RSS, after it adopted a written constitution committing itself to constitutional means and non-political engagement.

With Patel’s acerbic correspondence demanding a “written constitution” and “open activity” on behalf of the RSS still weighing heavy, Golwalkar met him on August 16, 1949. Subsequently, Patel wrote to Nehru that he told Golwalkar what were the “pitfalls” which the RSS should avoid… “I particularly emphasised completely eschewing destructive methods and adopting a constructive role”.

A newspaper report from December 17, 1949, on an event in Jaipur addressed by Patel, says he told the crowd that he had made his views very clear to Golwalkar when the two met. “The national flag must be universally accepted, and if anyone thinks of having an alternative to the national flag, there must be a fight. But that fight must be open and constitutional,” he said.

Congress and RSS

Soon after revocation of the ban on the RSS, Patel said: “I was myself keen to remove the ban and I issued instructions the very day I received Shri Golwalkar’s final letter agreeing to some of the suggestions we made.”

Patel added that “the only alternative to the Congress is chaos” and that he had advised the Sangh “to reform the Congress from within, if they think the Congress is going the wrong way”.

In his authoritative book on the Jana Sangh, titled “Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics”, B D Graham wrote that the RSS itself was open to the idea of aligning with the Hindu traditionalists within the Congress. “The links between the two organisations were more extensive than many suspected at that time: in the months following Independence, RSS workers in the United Provinces had been advised to try to convince local Congress leaders that not only was the RSS not opposed to the Congress but that senior Congressmen were sympathetic to its aims; and, in 1949, a newspaper report from the United Provinces commented on the sympathy the RSS derives from the rank and file of the Congress and also from a section of its leaders,” Graham wrote.

According to Graham’s book, the Congress Working Committee (CWC) even decided on October 5, 1949 that “members of the RSS could enrol themselves as members of the Congress”. Nehru was abroad when this resolution was passed, and could not attend the CWC meeting.

On October 10, 1949, then Congress president Pattabhi Sitaramaiyya said in Kanpur that the RSS “was not the enemy of the Congress”, and nor was it a communal organisation like the Muslim League and Hindu Mahasabha, Graham wrote.

However, on November 17, 1949, with Nehru in attendance, the CWC reversed its decision on the ground that no primary member of the Congress was allowed to join any volunteer organisation except the Congress Seva Dal.

Graham said Nehru might have been behind the decision not to allow RSS volunteers to join the Congress – something that the Sangh-linked magazine Organiser also stated on November 30, 1949.

In his book on the RSS, J A Curran claimed that Nehru, too, was on board regarding the October 5, 1949, decision, which was meant to test the waters as regards how many RSS volunteers would apply for the Congress’s primary membership, and how many within the Congress objected to it. Curran wrote that the Congress subsequently realised that there were few recruits and many objections.