As voters scramble to put together their papers for the Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) drive for new Bihar electoral rolls, the document most in demand is No. 6 on its list of 11 – a domicile or residential certificate.

One reason for this is that applicants are largely being allowed to submit just Aadhaar – the most commonly available document – as proof of residence to get a domicile certificate.

Ironically, Aadhaar itself does not figure in the list of 11 documents the EC has specified to prove date of birth / residence as part of the SIR.

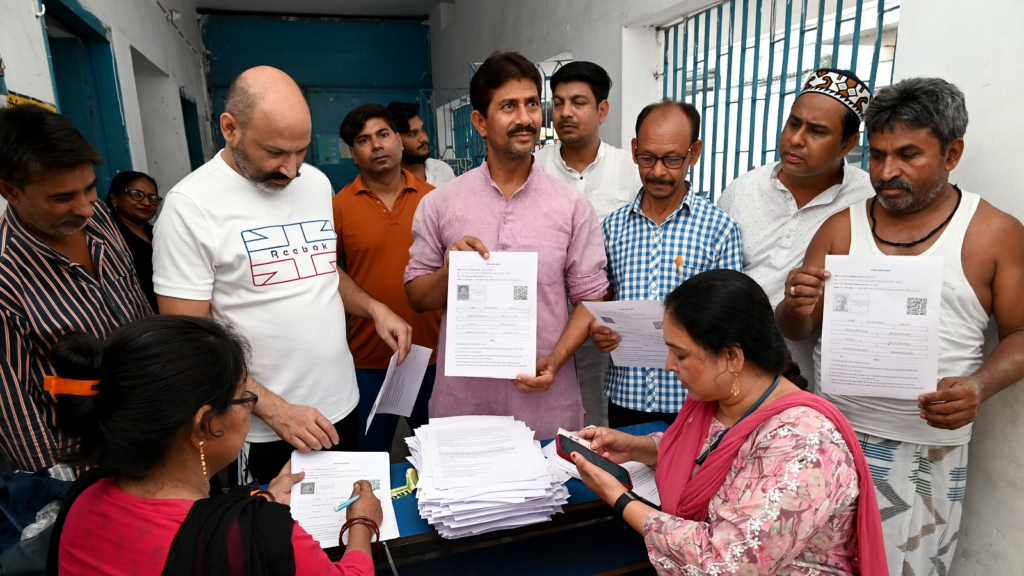

Between June 28, when the Election Commission rolled out its SIR drive, and July 6, 13,08,684 domicile applications had been received at Right to Public Service Centres located in each block – with applications pouring in at the rate of 70,000 per day. Officials said that 9,12,952 of these applications are still pending.

An RTPS official said: “The pendency is overwhelming given our limited staff strength. And it is expected to rise double fold in the remaining days (the last date to submit documents is July 25), with most people finding it easiest to get a domicile certificate as compared to other documents.”

For a domicile certificate, an applicant needs to provide Aadhaar, ration, voter ID cards, as well as a matriculation certificate and an affidavit confirming one’s permanent residence. But across RTPS centres, officials confirmed that they have waived off the other documents and are just asking for Aadhaar.

As a series of stories by The Indian Express from across 10 Bihar districts, covering Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s home district of Nalanda to RJD leader Tejashwi Prasad Yadav’s Raghopur constituency in Vaishali, and EBC and Dalit pockets of Darbhanga and Madhubani and Muslim-concentrated Seemanchal districts to upper caste settlements, showed, the one document (and often the only official document) villagers had was Aadhaar.

Mohammed Afsar Ali, a resident of Kasba in Purnia, questioned the logic of the exercise. “We can get a domicile certificate and a passport by producing Aadhaar, but Aadhaar itself is not important! This country has not been able to give us a permanent identification card in 78 years of Independence.”

Kishan Choudhary, a resident of Saurath, Madhubani, said: “I am among the lucky few who have been able to get a domicile certificate. It mentions my parents’ names and address.” According to him, about 3,000 people in his village panchayat are still waiting for their domicile certificates.

R K Jha, also a resident of Madhubani, is among those waiting. “I applied for a domicile certificate for four members of my extended family. With the deadline approaching, we are panicking,” he said.

Akshay Kumar Singh, an employee at the Vidya Vihar Institute of Technology, Purnia, said: “As an administrator, I have seen that only students or government job employees apply for domicile certificates.”

Chimaya N Singh of Srinagar, Purnia, said he hardly knows anyone with a domicile certificate in his village. “It is needed only when one’s son or daughter gets a job.”

Meanwhile, at RTPS centres, staff are working round the clock to clear the applications, with staff crunch and weak Internet service slowing them down. An official said that they generally clear an application within five-six days, well short of the 15-day timeframe. However, given the flood of applications, this is proving difficult.

Describing it as “overload of the system,” an official at a Patna RTPS said: “Those who apply over the next 10 days might not meet the July 25 deadline.”