“This electoral roll revision in Bihar can become bigger than Operation Sindoor” — so said a veteran tracking the political scene.

The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) — such a far-reaching exercise has never been undertaken before — has created widespread concern, in some circles even consternation. The Election Commission of India enjoys the constitutional right to revise electoral rolls, to ensure that elections are free and fair. There is, however, a difference in the way it is going about it this time.

The SIR exercise is not about “inclusion” of those left out, but more about “exclusion” of those who cannot prove their place and date of birth, or in effect citizenship — with the burden of proof shifted to the voter, rather than resting on the EC, as was the case earlier.

Voters are expected to provide documents to prove their credentials. Not the commonly available Aadhaar or ration or voter ID cards, but papers like proof of ownership of land or a passport or government employment proof – running the risk of recognising those as voters who are landed, wealthy and educated.

Just consider this — the Election Commission of the world’s largest democracy no longer recognises its own voter ID as good enough to accept a bona fide voter.

The timing of the exercise, three months before the high-stake elections in Bihar, which could set the tone for the many state polls due next year, is curious to say the least. That the BJP wants to win Bihar, is keenly interested in wresting West Bengal from Mamata Banerjee, and in retaining Assam, all going to polls within a year — thus giving it a grip over eastern India, as part of its long-term plan — goes without saying.

Illegal migration from Bangladesh into the eastern states — a long-standing concern of the BJP — has been an emotive issue over decades in the region.

But the haste with which the SIR is being carried out is problematic — it gives little time to those unfairly excluded to complain or for redressal of their grievances. The time constraint also gives more discretionary powers to Electoral Registration Officers (EROs), mandated to take decisions over whether to accept the documents given by the voter.

But that is partly a procedural problem. Opposition parties have expressed fear that the revision may disenfranchise Muslims, who are not known to vote for the BJP but are the mainstay of many on their side. The implications of disenfranchisement can be enormous — from not being able to get passports, or secure admissions or jobs. But many Muslims, wary of the BJP government, may well have got their documents in order for an eventuality like this.

Those likely to be most affected are the poor of Bihar – and the poor of India, if the exercise is extended to the whole country.

The Constitution makers ensured each adult Indian a vote, to choose or reject their rulers every five years. This was irrespective of any other criterion – of education, wealth, property, race, creed, language, religion or caste.

The “poor” who may be affected by the SIR exercise will overwhelmingly comprise the OBCs, EBCs, Mahadalits, Pasmanda Muslims and women, whom the BJP has wooed assiduously, and whose support it has gained in successive elections. Women migrate after marriage, and may have even fewer documents; they form the vote base of both Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his ally and Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar.

Successive PMs — from Indira Gandhi to V P Singh to Modi — went on to learn that it is the poor who determine the outcome of elections in India. Modi mentioned the word “poor” in his first speech after taking over as PM in 2014 — unlike the BJP of earlier years, which identified more with the middle classes (and was known as a Brahmin-Bania outfit).

“Agar hamare vote ke saath khilwarh hua,” a taxi driver said to me, “toh Bhagat Singh paida ho jayenge (If our votes are meddled with, there will be many Bhagat Singhs).” His words show the emotions surrounding the power to vote. This is visible on voting day when people, dressed in their best, line up from early morning in long queues, particularly in poorer areas, waiting to press that button, conscious of their power to elevate or demolish the powerful, and hold them to account.

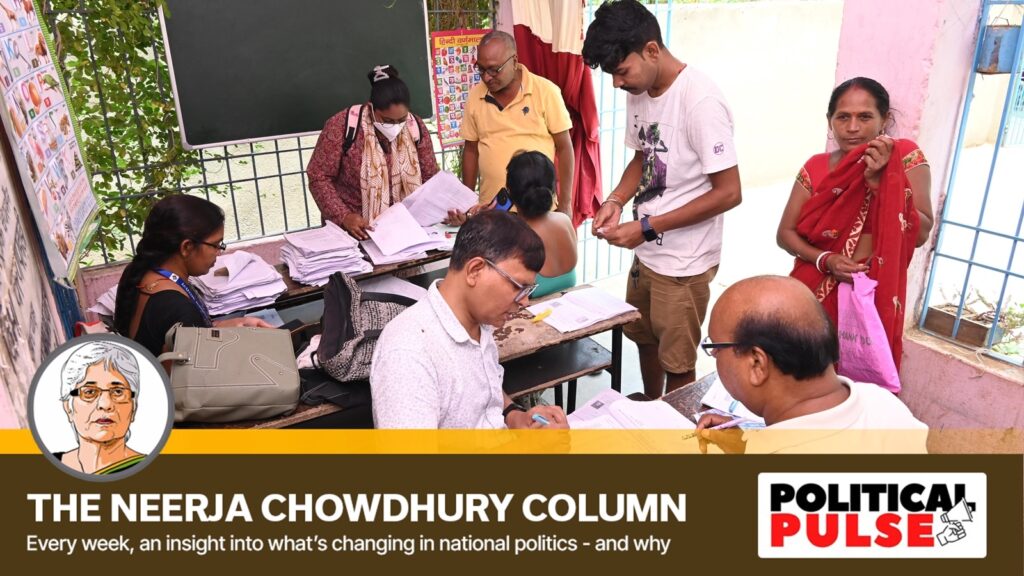

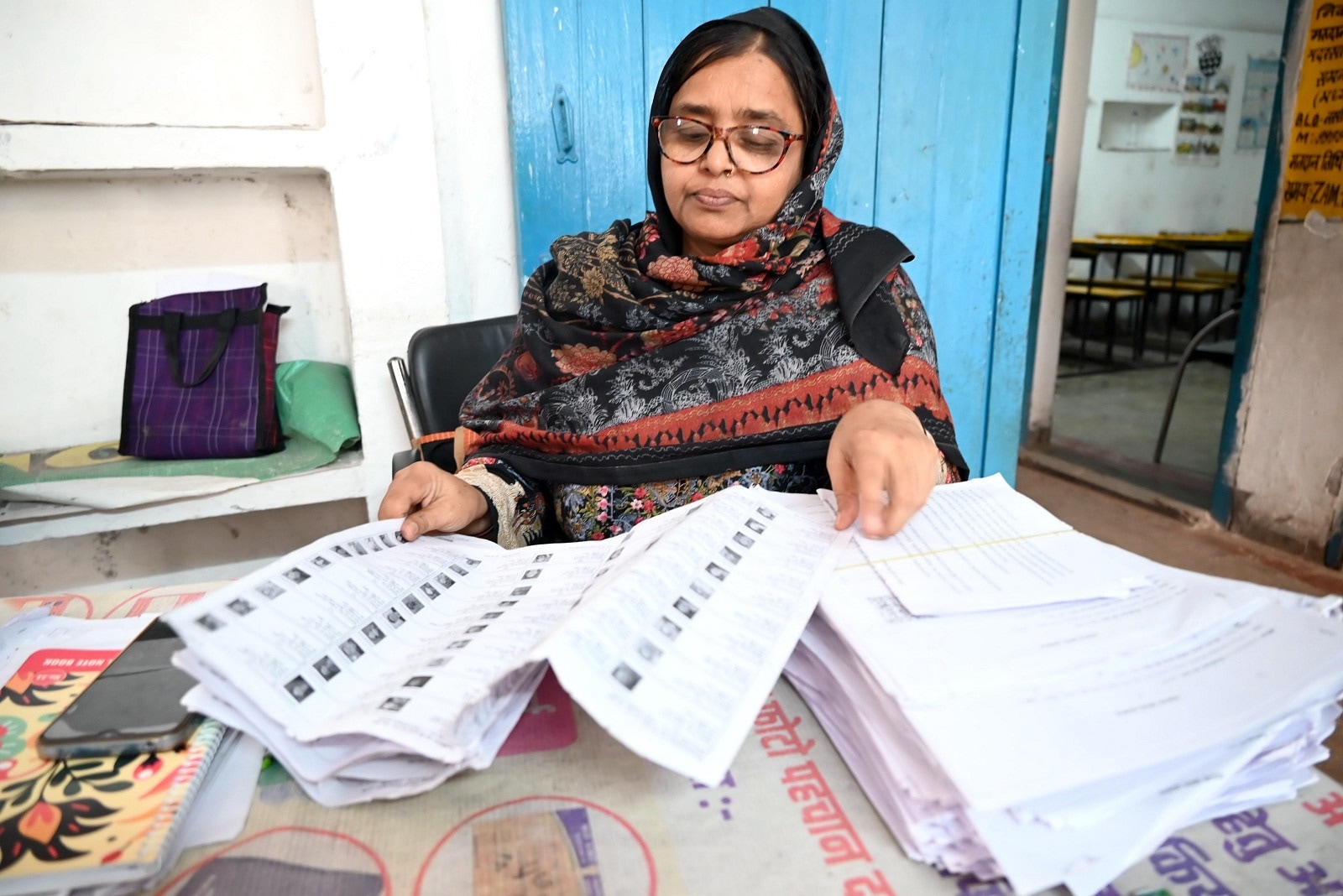

Booth-level officers during electoral roll revisions for the upcoming Bihar assembly elections. (Express Photo: Rahul Sharma)

Booth-level officers during electoral roll revisions for the upcoming Bihar assembly elections. (Express Photo: Rahul Sharma)

The BJP in Bihar looked confident about winning the Assembly elections due year end. But today, many BJP leaders in the state are restive, worried about the impact the SIR might have on the party’s prospects. Even if the BJP and its allies win, the credibility of the exercise could come into question. If there is a ripple effect because of people getting disenfranchised because they don’t have the necessary documents or because they have migrated to other parts of the country, the impact would be difficult to predict.

With instructions given by the EC to all states to get ready for the SIR – even as the Supreme Court is hearing the matter – the exercise in Bihar is clearly more than just a trial balloon.

BJP and RSS circles maintain that one reason for the rise in population over the years in the country — about 100 crore in 2000 to an estimated 140 crore now — points to illegal immigration into India, particularly from Bangladesh. It is a problem the Government of India cannot wish away, nor can India indefinitely absorb the influx. But should genuine voters on electoral rolls be thrown out or harassed or punished for the inefficiency of the Government over the years, no matter who was in power?

Even as a citizen is equal to a voter, if over the age of 18, surely the citizenship question has to be addressed separately from the revision of voter rolls? And as the Supreme Court has pointed out, it cannot be the EC which deals with the preparation of a citizens’ register.

On the ruling side, BJP ally TDP has underlined these concerns — that the exercise should be about votership, not citizenship — and that enough time should be allowed for it.

Finally, a word about the issues India should flag in 2025. Clearly, these should be health, education and skilling of 65% of Indians under 35 (around a billion in numbers) to hold their own in a world that is becoming increasingly “heteropolar”with multiple identities (like Elon Musk) influencing global decisions.

The question then is this: Will those who built the world’s largest political organisation (the BJP) and a formidable election machinery to lead the government in the world’s largest democracy, confine themselves essentially to playing identity politics (this applies equally to the Opposition)? If yes, it is deeply disappointing.

Neerja Chowdhury, Contributing Editor, The Indian Express, has covered the last 11 Lok Sabha elections. She is the author of How Prime Ministers Decide