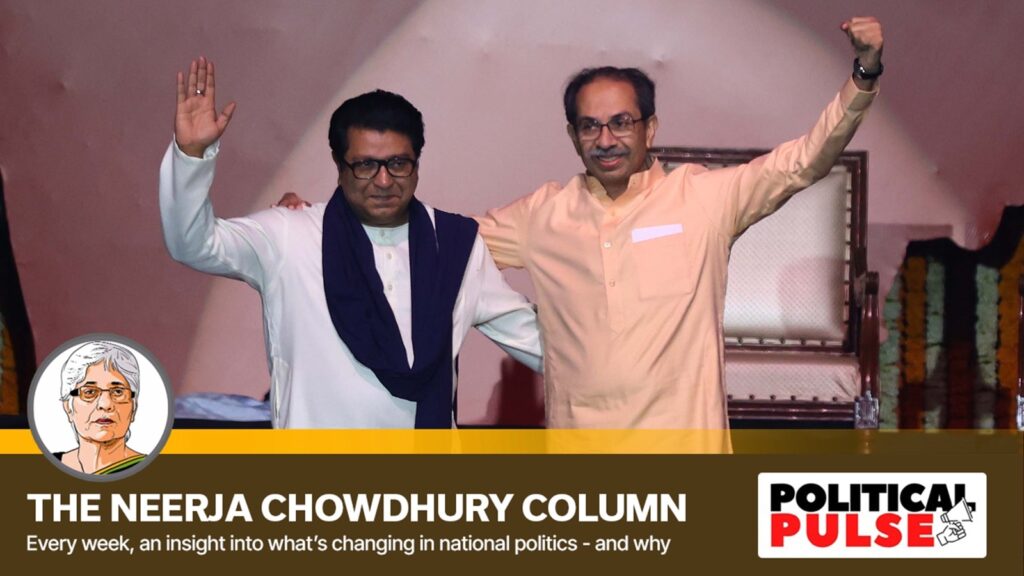

As former Maharashtra Chief Minister and Shiv Sena (UBT) leader Uddhav Thackeray walked onto a stage in Mumbai’s Worli last week and embraced his estranged cousin and Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) chief Raj, a loud cheer went up. The Thackeray brothers sat side by side after a gap of 20 years to celebrate the BJP-led Mahayuti government scrapping the move to introduce Hindi as a third language in primary schools, with everyone wondering how this turn of events will shape state politics.

Uddhav made no secret of their intention. Nudged by the Supreme Court, the elections to the cash-rich Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) — it has a budget larger than that of several states — and other local bodies will be held in the coming months. And the cousins are resolute about capturing them.

In a sarcastic dig, Raj Thackeray thanked Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis for making possible what Shiv Sena founder Balasaheb Thackeray, his uncle and Uddhav’s father, could not achieve: bring the cousins together. The government first made Hindi a compulsory third language in Classes 1-5 in state schools, and as the Thackerays took up the issue of “Hindi imposition”, Fadnavis moved with alacrity. The government made Hindi an optional third language, and then withdrew the directives altogether.

The MNS chief, known for his oratory, organisational skills, and seen as Bal Thackeray’s natural successor, had walked out of the Shiv Sena in 2005 after the party patriarch chose Uddhav over him. He formed his party the following year, but it turned out to be more of a spoiler than anything else. Even as Raj drew crowds at his meetings, he did not mop up votes and was down to a vote share of just over 1% in the Assembly elections last year.

Uddhav’s woes have also grown after the BJP split the Shiv Sena in 2022, costing him the CM chair. In the Assembly polls, he was down to 20 seats (out of 288) and only 9.98% of the popular vote. So, the brothers had little to lose and everything to gain, and they buried their differences to come together.

What happens next will depend on whether chemistry can trump arithmetic. The chemistry they generate will depend on their ability to hang together, though Uddhav said at the “victory rally” they had “come together to stay together”. The Shiv Sainiks present at the NSCI Dome in Worli applauded after every other sentence Raj and Uddhav uttered. But the real test will be the seat-sharing talks for the BMC polls.

Uddhav Thackeray and Raj Thackeray during their victory rally in Mumbai. (Express Photo: Amit Chakravarty)

Uddhav Thackeray and Raj Thackeray during their victory rally in Mumbai. (Express Photo: Amit Chakravarty)

Impact on other players

At present, there are three claimants for the leadership of the fragmented Sena. Besides the Thackerays, there is Deputy CM Eknath Shinde who is heading the Shiv Sena, the largest group with 51 MLAs, and will watch, hawk-like, every move the new jodi makes to dent his party’s support base.

Just as the cousins see the BMC as the route to power in Maharashtra, Fadnavis sees the BJP’s bid to wrest control of the civic body from the Sena as a way to consolidate his hold on the state. Will the cousins now force the BJP to opt for alliances for the BMC elections, instead of going it alone as the ruling party had hoped for?

The Raj and Uddhav reunion is a testament to the Congress’s inability to set an agenda to counter an increasingly dominant BJP. No senior Congress leader was present at the Thackerays’ rally. The party is apprehensive about the impact the duo may have on the non-Marathi-speaking vote base in the state (just more than 30%, though the Marathi-speaking population in Mumbai is only around 30% at present).

There is also a weakening of Sharad Pawar as a pole in the Opposition Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA). While he was not present at the rally, his daughter and Baramati MP Supriya Sule sat in the front row. The NCP (SP) working president was also seen getting Uddhav and Raj’s sons Aaditya and Amit ready to be photographed with their arms around each other. The NCP (SP) may hope the Thackerays will provide a new pole around which the MVA can re-coalesce. This comes at a time when many in the Pawar camp want to join the Ajit Pawar-led NCP. The Deputy CM is not so keen on the idea, though he goes out of his way to do the “work” of his former colleagues and keeps them in good humour.

Beyond the immediate politics, the coming together of the cousins poses larger questions. Can this lead to a Marathi versus non-Marathi polarisation in the months to come, and a deepening of the Gujarati versus Marathi faultlines?

The Thackeray cousins resisted the “imposition” of Hindi to protect Marathi asmita (pride). But, the irony is that the actions of MNS workers on the ground — they assaulted a shop owner in Thane for not speaking in Marathi — show they are insisting on “imposing” Marathi on all who live in the state. At the rally, Raj Thackeray, in the characteristic manner of the Sena of yesteryear, said there was “no need to beat people if they don’t speak Marathi, but if someone shows useless drama, you must hit below their eardrums”.

Under Uddhav’s stewardship, the Sena’s image has softened. But this time, like his cousin, the usually mild Sena (UBT) chief struck a harsher note, saying, “If we have to be goons to get justice, we will do goondagardi.” While people from outside a state should speak the local language, it should never be through coercion.

A different Maharashtra

The Maharashtra of 2025 is not the state it was in the 1960s, 70s or 80s, where the identity politics that the cousins are espousing worked. Mumbai, the country’s financial capital, is rapidly growing, and so is Bollywood’s outreach, spreading the influence of Hindi more effectively than anything else. The service sector in the city is also expanding quickly as aspirational entrepreneurs and migrants from different parts of the country seek its shores in search of opportunities, all requiring skills other than just the knowledge of Marathi.

The coming together of Uddhav and Raj could have been a seminal moment in the Maharashtra story. They could have put out a new message in a new language for a new way forward, all the while keeping Marathi asmita as one of the elements in the vision. But it was more of the old.

Even those who live in the state’s hinterland now want to reach out to the world beyond them. On a visit to Nandurbar, a tribal-dominated district in north Maharashtra, I visited an interior village to look at a project. “What if I were to tell you that I would convey to the PM what you really seek? But it has to be your dearest wish, not a string of wishes,” I asked a couple of hundred people who sat under the trees listening. Three women stood up, replying in unison, “We want an English medium school here.” To them, the language was a doorway to opportunities they had not received so far.

(Neerja Chowdhury, Contributing Editor, The Indian Express, has covered the last 11 Lok Sabha elections. She is the author of How Prime Ministers Decide)