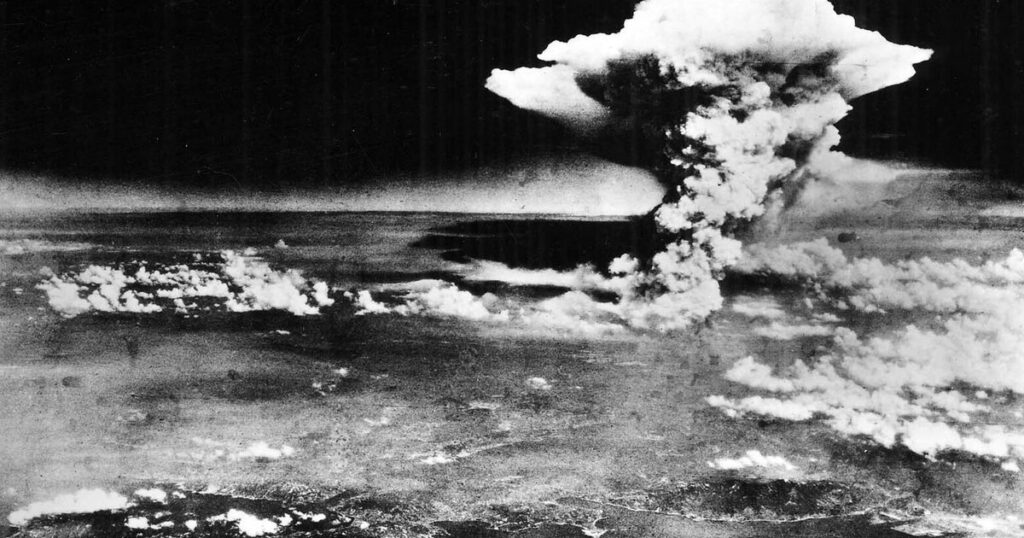

HIROSHIMA, Japan — The photos are in black and white, but for once that is not a total misrepresentation of reality. When the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on Aug. 6 and 9, 1945, two Japanese cities were instantaneously leached of color and life. In the aftermath of the world’s only nuclear attacks, what mostly remained were shades of a terrible gray.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki charred. They disintegrated. People and sparrows and rats and cicadas and faithful pet dogs — all that was alive a nanosecond before the mushroom clouds erupted in blue sky — exploded and then evaporated. They were the fortunate ones.

In Hiroshima, about 140,000 people perished by the end of the year. In Nagasaki, about 70,000 succumbed. Tens of thousands of the victims were children.

There are no photos of the immediate aftermath of the bombing, at least not on a human scale. For the survivors, though, the images of those moments never faded. Human forms staggered with strips of flesh hanging from their bodies. Eyeballs dangled from sockets. Everywhere, people screamed for water to cool their burning throats. In Hiroshima, they threw themselves into the river, which writhed with their torment until death freed them.

Those who survived that first day found little relief. Flies laid eggs in burns, then the maggots hatched, a perverse sign that life was continuing. Family members used chopsticks to remove the infestations, but most victims died. The biggest danger was the radiation, which could not be seen in any hue. People who seemed fine days after the bombing suddenly collapsed and died.

Survival often meant burns that formed excruciating keloids or internal organs that were eventually invaded by cancer. For many of those who made it through, decades of stigma followed. To be a hibakusha, as the survivors of the atomic bombing are known, was to live as a poster child of nuclear horror. Marriage prospects withered. Survivors worried about passing on disease to the next generation.

No one yet understood the full scope of what destroying and irradiating two cities meant, for the people or for the land. What did it mean to live poisoned by radiation? Or to eat from a plant growing in the toxic soil? Who would take care of the children who had lost their parents? Who would rebuild these lost cities?

To look at photographs of Nagasaki and Hiroshima after the bombings, especially ones from the sky, is an exercise in subtraction — and abstraction. Almost nothing is there.

More than the absence or the faint outline of humanity, what is seared in the collective consciousness is the terror that a mushroom cloud can bring. Without context, the fluffy white clouds of an atomic bomb, billowing like floating sheep, might look harmless. But we now know they signify annihilation, not from nature but from humankind.

The bombing of Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. Aug. 6 was described by the Americans as a necessary evil to end Japan’s wartime aggression and bring to a close World War II, the world’s bloodiest-ever conflict. The detonation also announced to the Soviet Union that American science had prevailed in the nuclear race. But it’s harder, some say, to make the case for the second bombing of Nagasaki three days later. A city with one of the largest Christian populations in Japan, Nagasaki had long drawn foreigners to its port. Now, the city, like Hiroshima, is known to the world primarily for having been chosen by the Americans for a nuclear attack.

Eighty years ago, Hiroshima and Nagasaki burned from the bomb. They burned from the fires that were sparked by the bomb. And they burned from the mass cremations that kept the fires going until all the bones were purified.

On Aug. 15, Japan surrendered. The Japanese empire’s bloody march through Asia was over. But the impact on civilians lingered, both in the countries the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces had invaded and at home, where a nuclear Armageddon had come twice.

What remained of Nagasaki and Hiroshima were not simply vast graveyards of rubble but the strength of the survivors, who began to rebuild their lives and then their cities.

Fumiyo Kono, 56, wrote a bestselling manga series about the war, which prompted a hit movie, television show and stage musical. While she was born well after, even thinking about that day when Hiroshima was bombed, she said, made her physically sick. On trips to a museum memorializing the victims, she could not bear it. She did not know what to do.

“Maybe one day, the answer will come from your heart,” she said, of how to process the devastation of her hometown.

All she could do was draw: a mushroom cloud, a family and a story that unspools from there.

Hannah Beech is a New York Times reporter based in Bangkok who has been covering Asia for more than 25 years. She focuses on in-depth and investigative stories.