Half a world apart, the Tri-Cities in Washington and Nagasaki in Japan are linked forever by the birth of the Atomic Age.

In the community that became the Tri-Cities, workers raced during World War II to create the plutonium for the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, just three days after an atomic bomb fueled with uranium was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan.

At 11:02 a.m. Aug. 9, 1945, from 1,650 feet above Nagasaki, “Fat Man,” an atomic bomb fueled with Hanford site plutonium, was dropped.

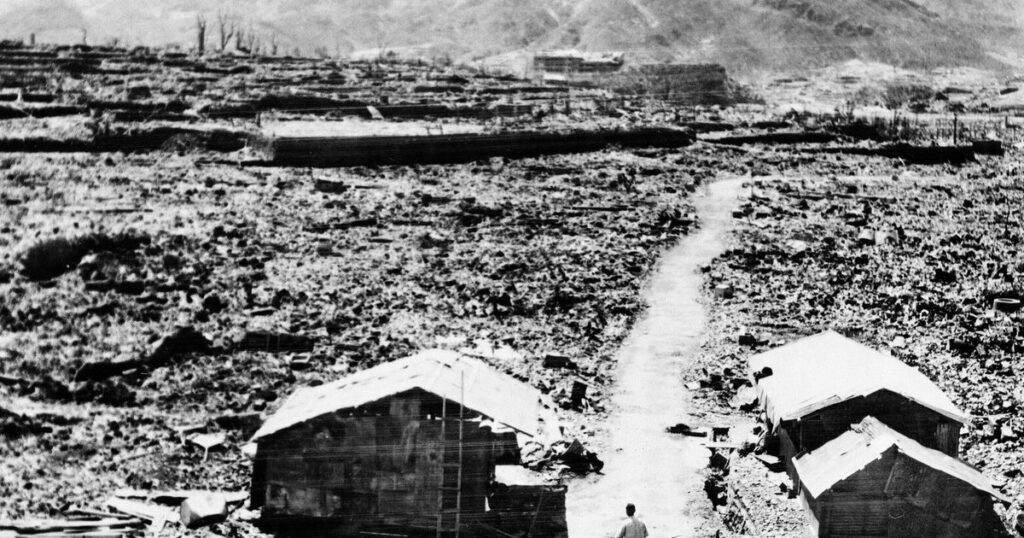

In one-fifth of one second, the fireball was a quarter-mile wide. Its mushroom cloud climbed to 30,000 feet in eight minutes. Heat vaporized humans into ashes. Rivers ran red with blood. The rubble that was once a city burned.

The mood in the United States was intense relief.

There would be no bloody battle from an invasion of Japan, with more American husbands, fathers, sons and brothers lost.

The secret project, created by tens of thousands of workers toiling long hours in the isolation of barren Eastern Washington, was a success.

Nagasaki: “Crying out for someone to kill me”

But in Nagasaki it was a time of immense suffering, pain and loss.

On the 80th anniversary of the bombing Saturday, most of those who survived it are no longer alive to tell their stories.

But 20 years ago, the Tri-City Herald interviewed Sumiteru Taniguchi, who was hospitalized for three years and seven months after being caught in the atomic blast as he was delivering mail or messages by bicycle.

The 16-year-old and his bicycle were catapulted a dozen feet and slapped against the road by a rainbow-colored blast.

“The ground seemed to quake and I clung to it for dear life,” he remembered.

He raised his head to see buildings in ruin “and bodies of children who had been playing at the roadside were scattered around me like clumps of garbage.”

“I thought I, too, was on the verge of death. But I spurred myself to stay alive,” he said.

He thought he was one of the lucky ones as he saw people writhing in pain on the ground, their hair gone and faces swollen.

When he reached a tunnel, where people were huddled in case of another attack, he asked a woman there to cut off the skin flapping around his arms. He felt no pain, he said.

But two days later, surrounded by the dead when rescuers found him, blood was dripping from his back and he was in intense pain.

He would lie face-down in a hospital for 21 months with massive bedsores forming on his chest, “crying out for someone to kill me.”

He survived and became a member of the Atomic Bomb Sufferers’ Council, carrying with him a photo snapped by U.S. Marine photographer Joe O’Donnell of his bloodied back.

In 1993 O’Donnell and Taniguchi met again, and O’Donnell photographed the tumors that were growing in the scars of the bomb survivor’s back.

The number of people who died in the Nagasaki bombing and later as the result of their injuries or exposure to radiation will never be known precisely.

However, the Department of Energy Office of History and Heritage Resources estimates that 40,000 died initially and 60,000 were injured. By the beginning of 1946 the number of deaths likely approached 70,000, with twice that number of people dead within five years.

Hanford: PEACE! Our Bomb Clinched it!

In the Tri-Cities, Americans weary of deaths and the war that had dragged on for nearly six years celebrated when the Richland Villager newspaper ran the headline “PEACE!” stretched across the entire front page. “Our Bomb Clinched it!,” it said.

It was Aug. 14, the day Japan surrendered, ending the war five days after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

Many of those in the Greatest Generation, either those who were veterans or helped produce the plutonium at Hanford dropped on Nagasaki, believed it was a necessary evil to end the war. In the last major battle before the atomic bombs were dropped, the fight for Okinawa killed 12,000 Americans, 90,000 Japanese soldiers and as many as 150,000 Okinawan civilians.

Roger Rohrbacher had worked in the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago where the chemistry was developed to separate plutonium from the irradiated fuel rods in World War II and then was sent to Hanford to work in the instrument department. His brother was in Europe in the 101st Airborne.

He told the Tri-City Herald when he was 85 that he believed his brother would have been sent to Japan, where casualties would have been heavy, if the United States had not dropped both atomic bombs.

His wife Mary, who was called “Bluey,” described the announcement of the end of the war in a 2004 interview that’s now kept at the Washington State University Tri-Cities Hanford History Project.

“Everybody was out celebrating,” she said. “The people next door to us were standing out there drinking a cocktail and the park was full of people celebrating, and it was just really an exciting time.”

Michele Gerber, a former longtime Hanford historian, recounted on the 60th anniversary of the Nagasaki bombing a conversation she had with Bill McCue, a young chemical engineer helping supervise the world’s first full scale nuclear plant at Hanford in 1945.

He told Gerber before his death in 2001 that he and his roommate were taken to a secret location during WWII and told what was being built at Hanford.

He and his roommate talked all night, asking, “Should be we doing this? Isn’t this God’s work?”

They concluded, “If God didn’t want us to do it, it will fail.”

He would repeat in other interviews that the bomb had been God’s will, and he didn’t question it.

In an interview with the Tri-City Herald, McCue said that “you cannot really reconstruct the urgency and distress of the times.”

“Sometimes you think you would like to put the genie back in the bottle, but you can’t. I don’t want anybody doing it to us and I don’t want us doing it to them,” he said.

The debate continues on whether the United States was right to use atomic weapons, forever changing the world with the threat of nuclear weapons.

Immediately after the 1945 bombings, 85% of people interviewed in a Gallup Poll said they approved of the atomic bombing of Japan.

A new poll by the Pew Research Center says today 35% of Americans believe the atomic bombings of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and the bombing of Nagasaki three days later were justified.

Some 31% said it was not justified, and 33% said they are not sure.

Peace ceremonies an ocean apart

In Japan on Aug. 9, remaining survivors, government leaders and others planned to gather at the Nagasaki Peace Park.

Traditionally, the ceremony includes the offering of water in honor of those who died in agony from burns. At 11:02 a.m., the time the bomb was dropped in 1945, the Bell of Nagasaki is rung, followed by a moment of silence.

At this year’s ceremony, Nagasaki Mayor Shiro Suzuki planned to call on world leaders to make a concrete plan to abolish nuclear weapons, he told The Japan Times. He also wanted to share messages from atomic bomb survivors calling out the cruelty of nuclear weapons.

In the Tri-Cities area, the Reach museum in Richland planned an event to fold origami cranes — a symbol of resilience, strength and peace — and to write and draw messages of peace on luminaria bags.

On Aug. 9 at 8 p.m., the Manhattan Project National Historical Park will display the luminaria in a Lights for Peace program at the fingernail stage in Richland’s Howard Amon Park.

The Columbia Mastersingers will perform, the public can wander the luminaria path in quiet contemplation and the Bell of Peace will ring out.

A Tri-Cities community group, World Citizens for Peace, which held the first annual peace ceremony in Richland in 1982, wrote to Nagasaki in 1985 requesting an object from the city to symbolize reconciliation.

Then Nagasaki Mayor Iccho Itoh sent a model of the Bell of Peace, a bell recovered from the ruins of Urakami Catholic Church and rung everyday to console the survivors of the bombing.

“I think the desire for peace is universal in the hearts of mankind,” said Richland’s Mayor Pro Tem Bob Ellis, when he accepted the bell in August 1985.

© 2025 Tri-City Herald (Kennewick, Wash.). Visit www.tri-cityherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.