For over fifty years, scientists have marveled at the ability of certain tissues to regenerate after severe damage. New research from the Weizmann Institute of Science, published in Nature Communications, uncovers the molecular mechanisms behind this regenerative phenomenon. The study not only clarifies how some cells resist death during injury but also sheds light on why some tumors become more resistant after radiation therapy.

The Discovery of DARE Cells: Unveiling the Self-Surviving Mechanism

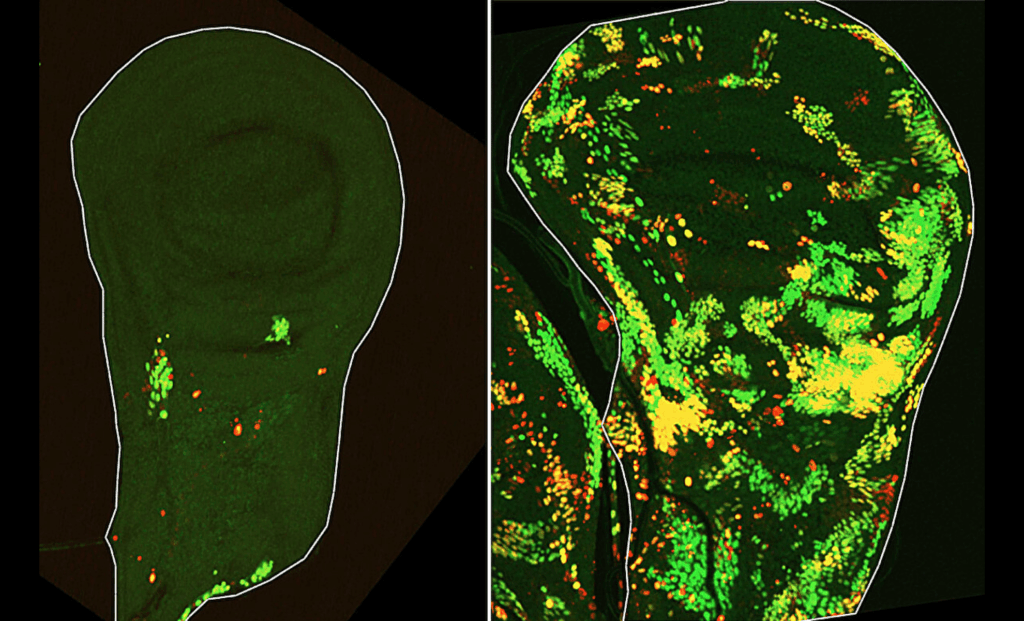

One of the most surprising findings from the study was the identification of a unique population of cells, dubbed DARE cells. These cells exhibit the ability to survive even after their death pathways are triggered. As Dr. Tslil Braun explains, “We set out to identify cells that push the self-destruct button but survive anyway. To do this, we used a delayed sensor that reported on cells in which the initiator caspase had been activated but that nevertheless survived the irradiation. This is how we discovered a population of cells we named DARE cells. Not only did these cells survive the irradiation, they multiplied, repaired the damaged tissue and replenished nearly half of it within 48 hours.”

The discovery of DARE cells provides a fascinating glimpse into how certain cells can bypass the usual mechanisms of cell death, even in the face of severe damage. These cells were able to not only survive but also contribute actively to tissue regeneration, quickly repairing a significant portion of the damaged tissue. The implication of this finding is profound, it suggests that the same molecular mechanisms that allow cells to regenerate might also contribute to the development of cancer resistance, especially in the context of radiation therapy.

The Role of NARE Cells in Tissue Repair

While DARE cells played a crucial role in the regenerative process, they were not the only players involved. The researchers also identified another population of cells, termed NARE cells, which showed no activation of the initiator caspase. As Dr. Braun notes,

“We identified another population of death-resistant cells, but unlike DARE cells, they showed no activation of the initiator caspase. We called them NARE cells. Although NARE cells ultimately contribute to tissue regeneration, they cannot do it alone: When we removed DARE cells from the system, compensatory proliferation disappeared entirely.”

NARE cells contribute to the tissue repair process, but they do not exhibit the same resistance to death as DARE cells. Their role is more passive, requiring the help of DARE cells for effective tissue regeneration. Importantly, the study found that DARE cells were activated by signals from dying cells in their vicinity, further emphasizing the complex and cooperative nature of the regenerative process. This intricate balance of different cell populations is crucial for preventing overgrowth and ensuring that regeneration occurs at the correct pace.

The Molecular Motor That Stops Apoptosis: A Key to Cell Survival

One of the most exciting aspects of this study was the identification of a molecular motor protein that helps DARE cells resist death. While apoptosis is normally triggered by the activation of caspases, the process is halted in DARE cells due to the action of this motor protein, which tethers the initiator caspase to the cell membrane. As Prof. Eli Arama explains, “We observed that although the initiator caspase is activated in these cells, the cellular death process stops there and does not progress to the next stage.”

The motor protein acts as a safeguard, preventing the activation of executioner caspases, which would normally break down the cell’s internal structure and lead to its death. This discovery has significant implications for cancer research. Overactivation of this motor protein has been linked to tumor growth, as it allows cancerous cells to avoid apoptosis. Thus, the same mechanism that aids in tissue regeneration could also be exploited by tumors to survive treatment, such as radiation.

How Resistance to Death Is Passed Down: Implications for Cancer Relapse

The researchers also explored whether the resistance to death seen in DARE cells is inherited by their progeny. This aspect of the study is particularly relevant for understanding cancer relapse after radiation therapy. Prof. Arama notes,

“We wanted to understand whether resistance to death is inherited by the descendants of death-resistant cells that survived the initial irradiation.”

The findings published in Nature, in showed that, after a second round of irradiation, the tissue demonstrated significantly fewer deaths than after the first exposure. Most of the surviving cells were descendants of DARE cells. “We found that when the same tissue is irradiated a second time, the number of cells that die during the first few hours is half that seen after the first irradiation, and most of the dead cells belong to the NARE population. In other words, the descendants of DARE cells were found to be exceptionally resistant—seven times more resistant to cell death than cells in the original tissue.”

This enhanced resistance may explain why tumors that regrow after radiation therapy often become more aggressive and resistant to further treatments. The survival of DARE cells and their descendants could help tumors evade the effects of radiation, leading to more difficult-to-treat, recurrent cancers. This discovery opens the door to new potential therapies aimed at targeting these resistant cells to improve cancer treatment outcomes.

A Delicate Balance Between Regeneration and Overgrowth

The study also revealed how the body maintains a delicate balance between regeneration and uncontrolled cell growth. The regenerative process is tightly regulated to ensure that tissue repair happens efficiently without leading to excessive proliferation that could result in tumor formation. According to Prof. Arama, “DARE cells promote the growth of nearby NARE cells, apparently by secreting growth signals. In turn, NARE cells secrete signals that inhibit the growth of DARE cells. In fact, we’ve discovered a negative-feedback loop between the two cell populations that prevents overgrowth.”

This negative feedback loop is crucial for ensuring that the regenerative process does not spiral out of control. It prevents DARE cells from multiplying excessively, which could lead to abnormal growth and, potentially, cancer. Understanding this balance is key to developing therapies that could enhance tissue regeneration without the risk of overgrowth or tumor formation.