A truly American genre, the Western extends beyond the reaches of its historical limitations and offers a narrative landscape full of myth and legend. From the beginning of motion pictures, the Western has been at the forefront of filmmaking, so it’s no wonder that it remains a genre that many fall back to over time. But when it comes to Western trailblazers that changed the genre forever, there are several films that come to mind. Frankly, there are even more than we could name here, but we’ve narrowed it down to 10 films in the 20th century that reinvented the entire genre — on some level or another.

Admittedly, surveying the entire collection of Westerns to find where some of these trends originated would be an impossible task. Instead, we’ve brought together some of the most popular movies of their day to note how they shifted the way horse operas were presented on the big screen. From John Wayne and Clint Eastwood to Kurt Russell and Kevin Costner, the genre is full of impressive names (and even more impressive features) that have elevated the Western and solidified its importance in cinema history.

So, without further ado, here are 10 of the most impressive Westerns that took the genre and turned it on its head. Without these films, it’s likely that the genre would not be what it is today, and it’s certain that the Old West cowboy wouldn’t be the American icon it is now. So saddle up, because it’s time to chase that horizon.

Stagecoach (1939)

In 1939, both director John Ford and leading man John Wayne had been around Hollywood for some time, but it wasn’t until the release of “Stagecoach” that the pair were ushered into the forefront as the premier Western filmmaker and star. Before this, the horse opera was generally relegated to B-pictures, with stars like Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, and Tom Mix heralding the charge. Even the Duke himself was a B-movie hero, starring in short features and film serials throughout the ’30s. But when “Stagecoach” hit theaters, the whole genre was thrust into the forefront, proving that it was truly A-list material.

Considered one of 11 near-perfect Western films, “Stagecoach” was celebrated for its incredible production value, intricate characters, and classical tale of the American frontier. It was one of the first major motion pictures to be shot in Monument Valley in Arizona and Utah, which would become one of the genre’s most iconic landscapes. It was nominated for several Academy Awards in its day, including best picture, and walked away with two. While all the classical genre elements of the Western had already been established at this point, “Stagecoach” helped cement them and thrilled audiences as it did so.

Young John Wayne is a powerhouse here as the Ringo Kid, who steals the show out from the rest of the bunch with little effort at all. While its portrayal of the Apache Indians is a bit cliched and has been rife with controversy over the years, “Stagecoach” set the stage for the Western’s extended run as Hollywood’s most prolific genre.

High Noon (1952)

While it may not be controversial by today’s standards, “High Noon” was a bit contentious in its day. For one thing, the film’s screenwriter, Carl Foreman, had been accused of being a Communist sympathizer, leading many to interpret it as an allegory for McCarthyism. Others have come to see Gary Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane as a man of justice and order standing against the lawlessness of the Old West, even if it meant he was standing alone. However you interpreted the film, “High Noon” made a massive impact on the genre.

The film played with well-established genre tropes, including giving its leading man a black hat to wear rather than the traditional light-colored headgear that would come to represent the Western hero. Of course, Cooper wasn’t the first Wild West lawman to wear a dark color, but when juxtaposed with the light-colored hats given to the villains, it felt as if director Fred Zinnemann was making a statement about who were labeled as the good guys and who were labeled as the bad.

John Wayne took it that way, famously stating in an interview with Playboy that “it’s the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life.” Indeed, Wayne’s longtime collaborator Howard Hawks felt the same way, notably making “Rio Bravo” — another phenomenal Western picture — as a response to “High Noon.” If one of the greatest Westerns of its day can directly lead to another, there’s no denying its impact on the genre.

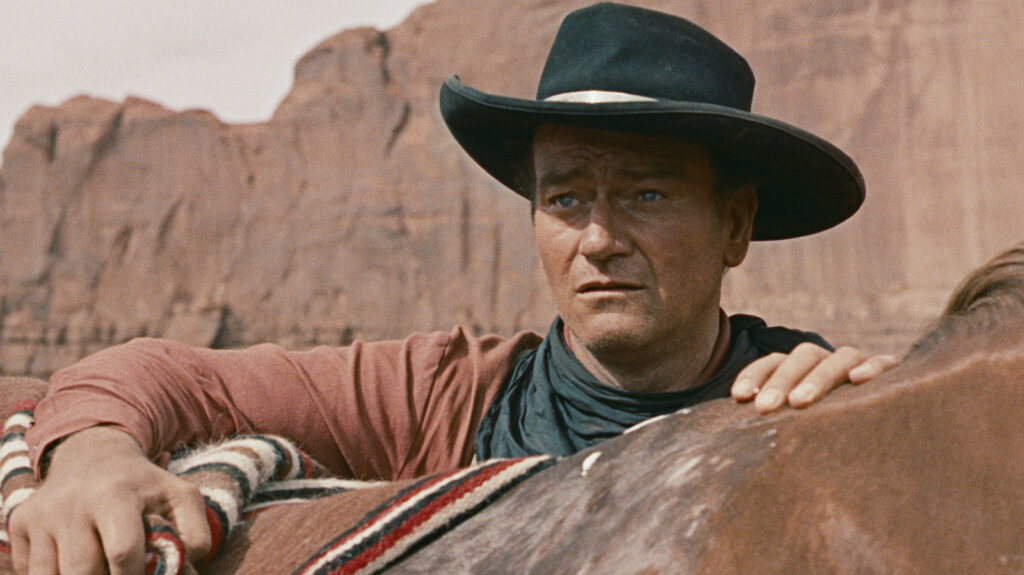

The Searchers (1956)

“The Searchers” is considered not only one of the greatest Westerns of all time, but also one of the most important movies ever made. Another collaboration between John Wayne and John Ford, the film follows Civil War vet Ethan Edwards (Wayne) as he and Jeffrey Hunter’s Martin Pawley scour the Old West in search of his niece (played by Natalie Wood), who was kidnapped by a band of Comanches. What seems like a simple plot is a remarkable piece of art that meditates on the horrific cycles of violence that plagued the American West, changing the landscape of the genre forever.

The 1956 picture is arguably most famous for its morally complex leading man, one who runs antithetical to the typical Western hero. While Edwards presents himself as a cool and calculating soldier able to make the tough decisions that most cannot, he proves to be just as affected by the cyclical rivalries and violent, often racist tendencies as even the most savage warriors on the open plains. Moving beyond traditional Western stock characters, “The Searchers” is a complicated character drama that elevates the genre beyond its conventions.

The John Wayne film that stands above the rest, “The Searchers” is a masterwork that sits firmly at the top of both Ford’s and Wayne’s respective careers. Nothing touches this one — armed with breathtaking cinematography that established the Western epic and performances that elicit raw emotion, it not only inspired future Westerns but films like “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Star Wars.”

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

When it comes to the most notable grizzled face of the Western genre, only two names come to mind: John Wayne and Clint Eastwood. While we’ve already noted Wayne’s two most important contributions to the genre, Eastwood’s “A Fistful of Dollars” changed it forever. No longer was the Western limited to simple U.S.-based productions. The first installment of Sergio Leone’s famed “Dollars Trilogy” was a success on all fronts as the first commercially successful Spaghetti Western, proving that the genre could be enjoyed by everyone, not just American audiences.

More than that, it expanded on the complicated hero that Wayne played in “The Searchers” by introducing the world to Eastwood’s “Man With No Name.” The film pushed away the old romanticized notions of “white hat” cowboy heroes and instead signaled a shift in the genre that promoted antihero archetypes who were gruff, rough, and dirty. Eastwood credits the film with launching his career, and although he had been a leading man on the television Western “Rawhide,” it was this 1964 picture that pushed him into international stardom.

Westerns were never the same after “A Fistful of Dollars.” The film didn’t just launch a trilogy of Eastwood and Leone shoot-’em-ups, but countless imitators that followed similar plots, introduced like-minded gunslingers, and revealed a grittier, darker, and more violent take on the American West.

The Wild Bunch (1969)

The late ’60s changed cinema forever, and the Western wasn’t immune to the wave of New Hollywood filmmaking that would spawn the blockbuster era we know today. But in terms of the gunslinging horse opera, 1969 was a significant year. John Wayne was back in the saddle in “True Grit,” Lee Van Cleef launched the “Sabata” trilogy, and Sam Peckinpah directed his landmark revisionist take on the Western in “The Wild Bunch.” Set in the early 20th century, the film followed a band of aging outlaws who set off on one last score as the world changes around them.

Where most Westerns of the day dealt in long takes that utilized the landscape and performances of their stars, “The Wild Bunch” employed modern filmmaking techniques, full of quick cuts and slow motion, to better emphasize the action on display. With this signature picture, Peckinpah conveyed a graphic realism like nobody had ever seen, even going so far as to add more modern weaponry. In fact, some say that the opening scene went too far.

As Michael Sragow wrote in his review for The Baltimore Sun, “What ‘Citizen Kane’ was to movie lovers in 1941, ‘The Wild Bunch’ was to cineastes in 1969.” While the “Citizen Kane” comparison may be a bit much, there’s no denying that “The Wild Bunch” offered something new for the genre. Challenging the audience’s perception of what the Western should be, “The Wild Bunch” is full of cinematic shock and awe.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

“The Wild Bunch” wasn’t the only massively innovative Western that hit theaters in 1969. Released only a few months later, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” is another one of those Westerns that you need to see before you die, if only for how much it impacted the genre going forward. As with the aforementioned film, it offers a more revisionist take on Old West outlaws and criminals, but instead of making them bloodthirsty and unrepentantly violent, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” makes its leading men sympathetic, intelligent, and chivalrous despite their vile acts.

Starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford as the respective pair of gunslinging no-goods, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” pushes past the familiar archetypes of heroes with strong moral codes and sends its leading men on the run from the lawmen on their trail. Each act of violence that Butch and Sundance commit is intentional, deeply affecting their character. While outlaws like Wayne’s Ringo Kid in “Stagecoach” had been romanticized by Westerns in the past, never before were they given the pure charisma and almost brotherly affection that Newman and Redford share here.

The film heavily employs witty dialogue that borders on philosophical and makes these gunslingers so downright likeable that you’re almost rooting for their latest get-rich-quick scheme. More than that, you hope (perhaps beyond hope) that they will learn to fill the holes in their lives that they’re desperately searching for. “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” seamlessly blends humor, action, and genre-bending suspense for a film that audiences were not quick to forget.

Young Guns (1988)

Admittedly, “Young Guns” is a bit of an oddball pick to put on a list of Westerns that revolutionized the genre, but hear us out. In the 1980s, the Western was no longer the genre it once was. John Wayne released his final picture, “The Shootist,” in 1976, Clint Eastwood’s only Western of the decade was “Pale Rider” in ’85, and Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate” had all but killed the genre in 1980. But “Young Guns” took the genre by storm when it set out to claim the younger American demographic that didn’t have the same affinity for the genre that their parents had.

By casting Brat Pack headliner Emilio Estevez as Billy the Kid, as well as Kiefer Sutherland and Charlie Sheen (with an uncredited cameo by Tom Cruise), “Young Guns” reinvented the wheel for the sake of America’s youth. While Westerns were always action-packed and loosely based on historical happenings, “Young Guns” leaned into the mythic persona of William H. Bonney and his outlaw Regulators as they boasted their MTV-era smiles and haircuts and “rebellious spirit” across the Old West. The film felt surprisingly modern and yet still maintained its 1800s setting.

Alongside its 1990 sequel, “Young Guns” infused the Western with modern rock and repackaged the genre’s traditional appeal for a new generation. Because the Western was on the decline, the Billy the Kid feature helped make the genre “cool” again as it had once been when Steve McQueen carried a Mare’s Leg on television. Soon after, the Western returned with a vengeance.

Dances with Wolves (1990)

Although not his first Western, “Dances with Wolves” is the film that forged Kevin Costner into the genre’s modern representative after Wayne and Eastwood passed the torch. In many respects, “Dances with Wolves” revived the Western genre. It took old genre cliches like the “white savior” trope and flipped them on their head, with its leading man, John J. Dunbar (Costner), being saved by the Sioux — and being unable to achieve their salvation. Likewise, the picture’s nuanced take on the differing Native American peoples was a major step in the right direction that led to better representation going forward.

While admittedly not perfect, “Dances with Wolves” proved that the Western wasn’t dead and still deserved to be taken seriously, especially after winning several Oscars, including for best picture and best director. It’s hard to understate the importance of this three-hour epic, which sparked a resurgence in the genre that hadn’t been seen for quite some time. It wasn’t just popular with certain audiences, like “Young Guns,” but it became something masterful and artistic that deserved to be acknowledged for its merits.

With “Dances with Wolves,” Costner established himself as a Western powerhouse, and though he hasn’t made nearly as many genre films as Wayne or Eastwood, he continues to return to the genre time and again. His passion for the Western is on full display here, as he meditates on a long-gone era that Dunbar watches fade right before his eyes.

Unforgiven (1992)

Riding off the trail blazed by Costner’s epic, Clint Eastwood returned to the Old West for one final time in 1992’s “Unforgiven,” and it was just as influential on the genre. While many Westerns of yesteryear spent time examining what makes the genre tick, “Unforgiven” fully deconstructs the Western hero by making Eastwood’s William Munny regretful for his lifelong career as a gunfighter, adding to his pain by way of consequence. But it’s more than regret that drives this flick, as it also sheds light on how Western myths were conjured, all while tearing them apart.

As gunslinger William Munny is brought back into the world of violence and gunplay, only to become the only man in town standing up for what’s right, Gene Hackman’s Sheriff “Little Bill” Daggett slowly falls into more despicable behaviors, failing at his duties as a lawman and crushing the traditional views of the Western hero. Again, these concepts aren’t entirely new to the genre, but the way “Unforgiven” tackles them with a modern, character-driven lens feels quite novel in practice. It also deals with the harsh reality of age, something that some of Wayne’s later pictures often danced around in practice.

“Unforgiven” was also an Oscar winner, one that still influences Westerns to this day. In fact, it was a major inspiration for Taylor Sheridan’s “Yellowstone,” largely due to the theme of consequences seen throughout. Easily Clint Eastwood’s best, it concluded his decades-long run in the genre in style.

Tombstone (1993)

With “Dances with Wolves” and “Unforgiven” breathing new life into the genre, “Tombstone” took the whole world by storm by elevating the genre’s mythic elements and infusing the tale with characters that dare not be overlooked — even if the film itself was grievously overlooked at the Academy Awards. Although the film suffered from a chaotic production, its stars, namely Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer, committed to their parts in ways that felt revolutionary when seen on screen. The script itself, written by Kevin Jarre, is Western gold, littered with inspired one-liners and layered material that further revealed the genre’s potential.

Despite being a heavily romanticized version of the Wyatt Earp story — especially compared to Kevin Costner’s historically accurate “Wyatt Earp” — “Tombstone” fully delivers with its fast-paced, character-driven, and action-packed drama that remains the standard for many modern takes on the Old West. Beloved by even those who aren’t fond of the genre, it proved that the Western didn’t need to revolutionize its plot but rather its characters, giving Kilmer’s Doc Holliday and Russell’s Wyatt Earp complicated motives and vices that put these men in unique, morally compromising positions as they fight for what’s theirs.

Whether you love “Tombstone” for its masterful screenplay, dynamic performances (Michael Biehn is also a knockout as Johnny Ringo), or the atmospheric landscape of late 1800s Tombstone, there’s a reason it’s considered one of the greats. Even 30 years later, “Tombstone” feels just as modern as if it came out yesterday, and that’s no small feat for a Western.